…not for God and country. That is clearly what the book Fortune’s Soldier tells us about the motivations of the adventurers whom the East India Company brought to India in the 18th century

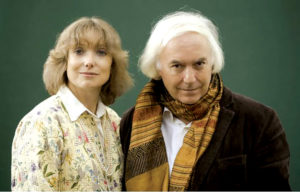

Alex Rutherford is the pen name of London-based couple Diana Preston and her husband Michael, authors of the six-part series Empire of the Moghul, which sold two lakh copies in India. As such, his latest tome Fortune’s Soldier (Hachette, 414 pages, Rs 599) covers ground he is well acquainted with.

This time, he has done a creative reconstruction based on the papers of envoy and espionage agent for the British East India Company, Nicholas Ballantyne. This young man is sent out from Scotland by his uncle, who is about to become part of the Jacobite rebellion against the British monarch, to make his fortune in India, as “There is nothing for you in Scotland – make Hindustan your home and prosper there – and do not think too harshly of your loving uncle…”

As historians have amply recorded, the conquest of India on the pretext of securing trade saved England’s economy at a time when it was precarious.

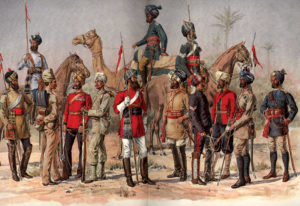

In a way, the two countries had similar problems — petty monarchs fighting each other for power and pelf, the desire of the well-heeled for imported goods and foreign women, and rigid class/caste divisions. Agents like Ballantyne were deployed to engineer rivalries in royal courts, to look for opportunities for trade, to oust the other European powers. What we often forget in India is that the Highlanders (Scots) were treated by the ruling class as less than human “and were happy to see the government use its share of Company profits to fund their repression.”

Supposedly, the reader (even if she is Indian) is being encouraged to feel empathy for the protagonist. Ballantyne’s fearlessness in battle and his love for an Indian woman with whom he has a child will naturally endear him to us. Those who are part of the English-speaking elite will feel a grudging respect for him, for this is our colonial hangover, this is how we have been co-opted into thinking we were given a noble system of governance and modern values of equality and fraternity. Yet even the East Indian Company officials are shown as colluding with the French, striking shady deals with them, even selling them arms.

The hypocrisy of the British is called out by Nawab Siraj-ud-dulla in Calcutta, sometime in 1756-57, when he meets Ballantyne:

The Nawab’s eyes flashed with scarcely concealed hostility. ‘You speak as if the Company treats my state as an equal partner in their schemes. They do not! They are never satisfied, always asking for more. Like leeches you are sucking my land dry. The terms of the trading privileges you have extracted from my predecessors mean that the Company and its officials – nor I and the people of Bengal – are the ones to prosper. All the Company wishes is to grow rich and carry off our wealth to your raining islands – something my grandfather – mighty and respected ruler though he was – did not always realize. The Company must understand you and I are different people.’

Politics aside, readers abroad must be fascinated by the local colour that suffuses the narrative. It’s all there – the tiger hunt, the elephants, the fishing boats, the dacoits, Navroz celebrations – but India and Indians are just a backdrop for the story of the British in India. It makes for good cinema, even good historical fiction, but is not of much use to social scientists. The unwavering loyalty of the Indian assistant is familiar but still sickening to behold.

Why were we so passive when everybody was stomping around our land, imposing impossible taxes, humiliating us? If we were so other-worldly, so self-abnegating, how have we become so materialistic now, just half a century after Independence? How come we accepted globalisation so readily? No clues are to be found here, of course.

Be that as it may, the book seems to be mis-sold in the subcontinent as ‘the epic story of Robert Clive and the dawn of the British empire in India’.

True, Clive is sharing a cabin with Ballantyne on the boat when they sail in the Winchester from London’s Wapping Docks. Clive is quite a character, packed off to India by his family because of huge gambling debts. He is also a rogue, with his outrageous behaviour and willingness to launch into misadventures, proclaiming “Caution is for cowards”.

Clive flits in and out of the story, with the friendship between the two turning to hostility when Clive marries the heiress whom Ballantyne rejects. In the last few pages of the book, though, he plays his decisive role in history by sending Ballantyne to persuade Mir Jafar to betray the Nawab and serve the British cause. Clive has already received secret messages from commanders in the Nawab’s army that they would be willing to switch sides for a consideration. Whereas there are officers in the East India Company who are willing to sell out its interests to the Nawab! Quite a bunch of opportunists on both sides.

Thus it came to pass that Robert Clive went on achieve his decisive victory at the Battle of Plassey on June 23, 1757. The then Prime Minister William Pitt Sr described him glowingly in these words: “We had lost our glory, honour, and reputation everywhere but India: there the country had a heaven-born general, who had never learned the art of war, nor was his name enrolled among the great officers who had for many years received their country’s pay; yet was he not afraid to attack a numerous army with a handful of men.’ The UK’s National Army Museum, however, painted a fairer picture: “A courageous and resourceful military commander, Major-General Robert Clive helped secure an Indian empire for Britain. He eventually became an imperial statesman, but also a greedy speculator who used his political and military influence to amass a fortune.”

Thus are myths fabricated and colonised people made to believe that there was something grand and noble about the conquest of their territory. The truth is stranger than such fictions.