Since Jawaharlal Nehru’s death, India has longed for a leader who upholds what is right regardless of whether it’s popular. The AAP chief is not that leader

IN HIS seminal work Republic, Plato introduces the concept of “philosopher-king” to describe an ideal ruler. Simply put, Plato’s philosopher-king would examine not only the issue at hand but also its root causes and implications before solving it. The philosopher-king derives pleasure not from the pursuit of power but from the pursuit of understanding. They love true knowledge and not mere experience or education. As the Greek philosopher himself put it, “True pilot must of necessity pay attention to the seasons, the heavens, the stars, the winds, and everything proper to the craft if he is really to rule a ship.”

Most leaders claim to work for the common good, guided by some deep ideology. But, ultimately, their lives are organised around the pursuit of power. Plato’s ideal ruler wouldn’t desire power and, thus, couldn’t be corrupted by it. The trappings of power mean nothing to them except insofar as they help him in his chosen task of governing.

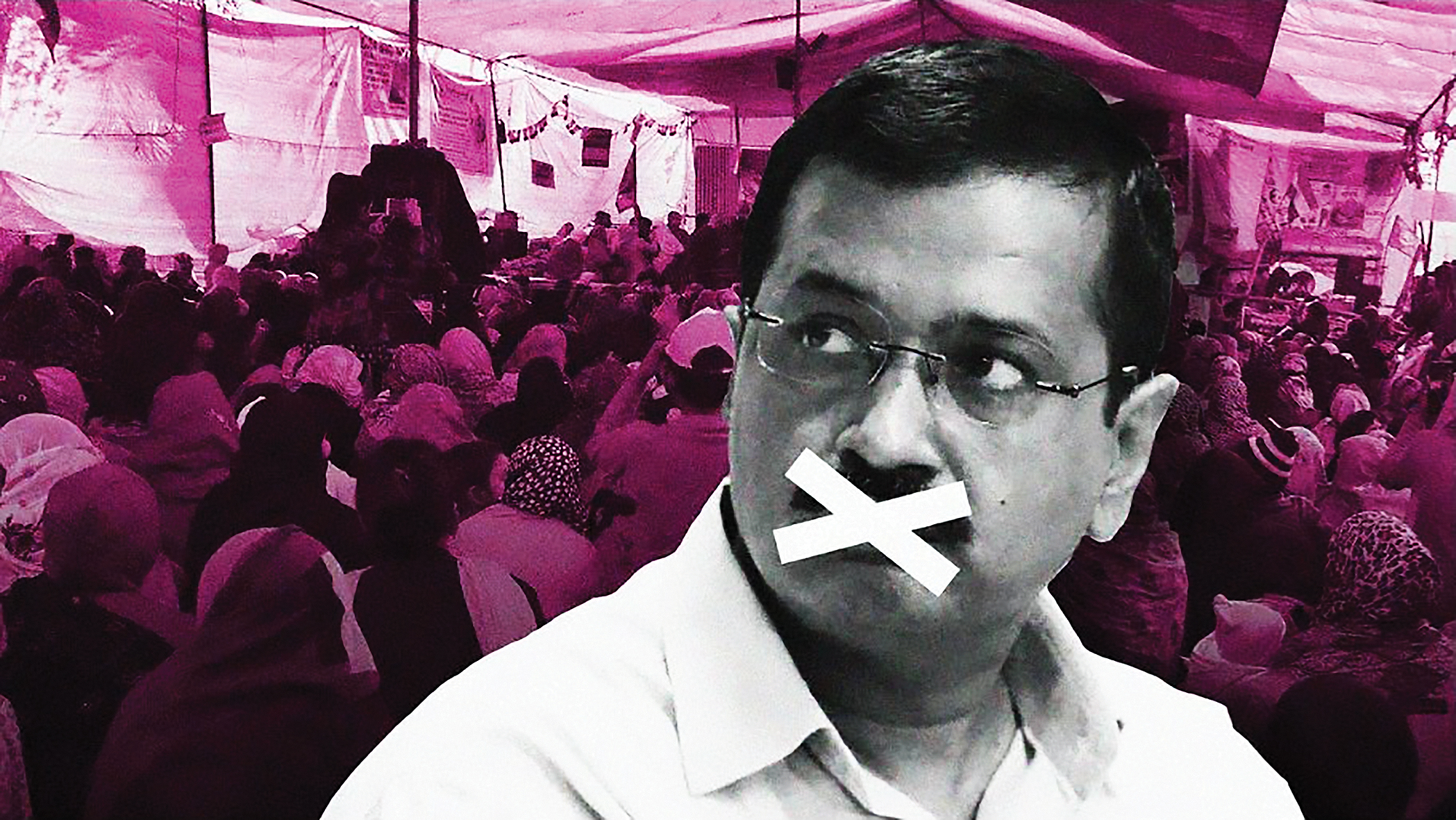

My reason for delving into Plato’s idea of the ideal ruler is to draw a contrast with the leaders’ modern democracies throw up. Specifically, Arvind Kejriwal, who has drawn flak for staying silent on the ongoing citizenship law protests, even during the Delhi election campaign.

So, why is he silent?

Well, let’s take a step back and look at Kejriwal’s origin story, his fight against corruption.

In India, political and bureaucratic corruption is a theme that has always dominated public discourse. But what’s corruption? Is it just financial or legal irregularity? Or can we locate it in the structures of the state? Would corruption end if we managed to eliminate opaque transactions of money without addressing structural issues? Such questions are neither asked nor encouraged as our education system and religious stories teach us to look at any problem through the neat paradigm of black versus white.

In this context, the kind of a neat solution you would expect to find is what movements such as the India Against Corruption offer: a law, more ruthless than it appears at first glance, which an unelected Lokpal would implement through a giant bureaucracy. The Lokpal would have the power to police everybody from the prime minister to the lowly government official. They would have the powers of investigation, surveillance and prosecution. In a nation where marginalisation is socially sanctioned through caste and class hierarchies, a call for pushing the state apparatus further back in the name of fighting corruption is not a good idea. As ideas go, however, it is surely simple and can be sold to the public without any accouterments of nuance.

Financial corruption does not exist in a vacuum. To realise that corruption is coded in the social system and is borne of inequity of privilege, and that’s the reason for our developmental rut, is to look in the mirror and accept that your privileged identity is part of the problem. This means questioning your parents, your religious philosophy, and the basic ideas you have held dear since childhood. It is much easier to find problems outside of us. In case of financial corruption, there’s a larger base to drive a revolution and everyone gets to think of themselves as a victim. Unlike in the case of social change, where the first step is to acknowledge privilege and, by extension, accept one’s own culpability. Birthing revolutions that seek to shape society are difficult because social structures are a part of us.

I am not sure if Kejriwal, while he was racking up all his glowing academic qualifications, ever had the time to reflect on these critical questions before launching his crusade against corruption. Sad as it’s, STEM education in India doesn’t provide the student with the tools for self-examination. It’s evident that Kejriwal finds it difficult to look beyond the immediate black and white and examine the situation deeply. His steadfastness in not commenting on the citizenship law protests is a glaring example. When an infantile argument is made about the protest at Shaheen Bagh causing traffic jams, Kejriwal’s first response is that the Delhi police is not under his control and that he would have taken care of the problem had it been.

Why a protest happens and why it is often about much more than the immediate demand it makes of power is a question that requires deeper examination. Protests, from the Dandi March to the Yellow Vests, are a display of the sheer power of public opinion. When an entire community is facing an existential threat – as the citizenship law and the National Register of Citizens seem to be for India’s Muslims – comparing it with traffic jams is naively dishonest at best and cruel at worst.

Since democratic institutions are set up to reward electability and not wisdom, we get leaders who are electable but lack acumen. Politicians enthrall us with simple slogans such as “Make America Great Again” or “Achhe Din” because they can mean anything to anyone as long as we don’t scratch the surface.

Kejriwal has been successful when it comes to breaking down issues into nuggets and offering simple solutions, not unlike Narendra Modi, who of course isn’t much of an examiner of human condition either.

Politicians like Kejriwal or Modi succeed because they would rather urgently tackle a problem they see than waste time weighing up all its aspects. So, Jan Lokpal or demonetisation gains public appreciation for trying to fix a visible social malice with a simple solution that does not need any intellectual investment. The philosopher king is good for a long-term vision but bad for the next election. Being noncommittal is politically prudent, for then you are everything to everyone and never too much of anything.

Politics as a mirror of the culture

“Politics is downstream of culture,” says the father of the modern American Alt Right, Andrew Breitbart. What he means is that our politics is a mirror of the culture it emanates from. To expect an Indian politician to completely put aside religion is to have him forsake any chance at getting elected. Unless there’s a strong ideological reason that drives a politician to stand with the minority group, there is no electoral benefit in publicly showing such support. This goes for Kejriwal as well. After all, ideology isn’t what moves him, it’s a sense of correcting problems as he sees them. His is the view of a technocrat, not someone who can weigh social equations. The problem is not Kejriwal, the problem is that the idea of majoritarianism has won mass support in India.

However, Kejriwal is also clearly a bit of an anomaly, which is the reason for this hullabaloo around him. It seems he is moved by more than power; he wants to change how politics is done and govern in the best possible way he knows. I do not doubt his intentions, just his understanding of what really ails our society.

Politicians are generally reflections of the forces undergirding the society. An elected politician represents the mandate of the people. This mandate allows them to veer within only a limited bracket of opinion. Of course, some of them transcend it, but there is no politician worth their salt who would present an opinion that’s too far from the mean of the constituency they represent. Kejriwal wants to fix healthcare and education which is a noble goal in a poor country. He is not bothered by questions about the idea of India or its social fabric and caste hierarchy.

What it means to be an Indian, per Kejriwal.

After 70 years of independence, we seem for the first time to be debating what it means to be an Indian. While the evolution of the citizenship law protests has started to respond to this question, at the political level it seems the non-Hindutva forces still do not have an answer. The opposition parties at some point will have to present their version of what it means to be Indian. Kejriwal, for now, seems happy letting the idea be defined by the BJP, while he creates a different niche for himself. This raises a key question: does the path that India is on bother Kejriwal? He supported the removal of Article 370 in Kashmir, so that tells me the answer is no.

So, who exactly is he a leader of and what precisely is his idea of India. I think we will find the answers in the next few years. But my fear is that the idea of India Kejriwal might offer wouldn’t be much different from that of the BJP. After all, his cultural background is the only philosophy that dictates his worldview and that background is steeped in the homogenised North Indian, Hindi-speaking notion of India.

This deconstruction of Kejriwal – one of India’s most successful anti-BJP politicians – isn’t to say democracy is inherently biased to thoughtlessness. Jawaharlal Nehru, for one, took decisions whose benefits only become apparent years after he was gone. But Nehru came out of the freedom struggle and, therefore, could afford to credit his reputation towards the greater public good. Modi also came in with a lot of credit as the Hindu Hriday Samrat and he has taken decisions – demonetisation, Goods and Services Tax – that have demanded much public patience.

Similarly, Kejriwal earned credit from his anti-corruption movement and has largely been a force for good in Delhi. However, when it comes to taking ideological positions, he comes up short. That’s simply because he doesn’t find provocative any issue where he must take a side after examining all its sociopolitical causes and consequences.

In spite of being dead for 56 years, Nehru seems to still offer the only credible idea of India that could take on Hindu nationalism. Since Nehru’s death, India has longed for a leader who would uphold what’s right regardless of whether it’s popular. A statesman who thinks not of the next election, but of the next generation. Kejriwal is not that leader.

www.newslayndry.com