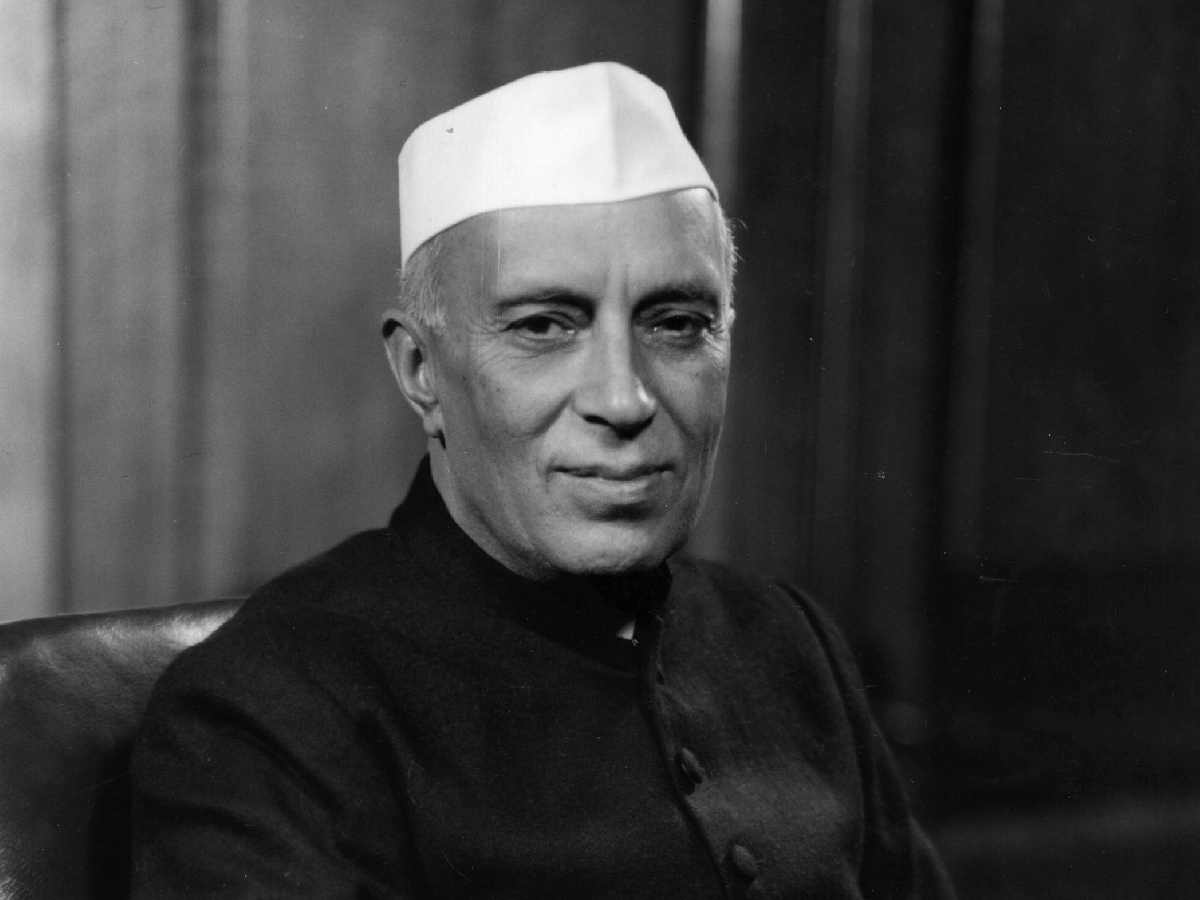

Imagine a Delhi without Buddha Jayanti Park, the Nehru Memorial Library, the Zoo, Nehru Planetarium, or even Rajghat. This might have been reality if Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru hadn’t invited two visionary young architects to help shape the capital’s landscape. During Nehru’s visit to America in 1949, a young architect, Rana Man Singh, attended one of his lectures. At the time, Rana was apprenticing with the legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright, having recently graduated in architecture from the JJ School of Arts in Mumbai. After Nehru’s talk at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Rana, along with Wright’s wife and daughter, had the chance to meet him. Introducing himself, Rana was met with an enthusiastic response from Nehru: “You are returning to India after your studies, aren’t you?” When Rana replied yes, Nehru simply said, “Meet me when you come.”

Also read: Celebrating Children’s Day: Bridging the divide with today’s digital generation

Meeting Nehru at Teen Murti

Rana continued training and working on various projects, including the design of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, before returning to Delhi in 1951. He began teaching architecture at Delhi Polytechnic in Kashmere Gate, which later became the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA). A year later, Rana met Nehru at his Teen Murti residence. Nehru recognised him instantly and asked, “Are you back?” Rana informed him that he was teaching in Delhi. “Very good,” Nehru replied. “We must put you to work.” Within weeks, Rana was appointed to the Central Public Works Department (CPWD).

From Buddha Jayanti Park to Shanti Vana

Between his return and 1964, the year of Nehru’s death, Rana worked on numerous significant projects. These included Bal Bhavan (1953) and the first India Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1964. Among his other major projects were Buddha Jayanti Park (1956), Shanti Vana Samadhi (1964), the India Pavilion at the Montreal Expo (1967), the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML, 1964), Nehru Planetarium (1980), the Nehru Memorial Library Annexe (1983), and the National Library in Kolkata (2005). The NMML is now known as the Prime Ministers’ Museum and Library Society.

Following Nehru’s death, Rana was entrusted with the design of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML). “Rana knew that his creation would be compared with Teen Murti, designed by Robert Tor Russell, who also designed Connaught Place, Western Court, Eastern Court, Safdarjung Airport, and many other buildings. Teen Murti was practically in shouting distance from the building Rana was designing. He did not disappoint his admirers with his classic design of NMML,” says Bakshish Singh, a veteran architect.

The distinctive design of NMML

Rana ensured that all library visitors could enjoy views of the lush lawns and manicured gardens, opting for larger windows to create this connection to nature. While many of his contemporaries, including Joseph Allen Stein (India International Centre, India Habitat Centre, and Triveni), JC Choudhary (Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi), CK Kukreja (Jawaharlal Nehru University), and Shiv Nath Prasad (Shri Ram Centre for Performing Arts, Akbar Hotel, and Tibet House), were inspired by architects like Edwin Lutyens and Le Corbusier, Rana sought to create something new and distinctive. “Rana was far ahead of his time. For NMML, he used wooden flooring, which was unheard of in the 1960s. Walking on wooden flooring is less tiring,” says Bakshish Singh.

Delhi indeed owes a great deal to Rana for the beautiful landscaping of Buddha Jayanti Park. In the early post-Independence years, Delhi saw a wave of new construction. At a meeting at Vigyan Bhawan to discuss how India would celebrate the 2,500th year of Buddha’s enlightenment, it was decided that Delhi should have a large garden symbolising the teachings of Lord Buddha. The committee, led by Vice President S Radhakrishnan, requested Rana to design the proposed garden, having been unimpressed by other submissions. Sadly, Nehru did not live to see his dream project in its full glory. Rana ensured that all visitors to the park would remember it for its calmness and peacefulness, qualities that echoed Buddha’s teachings.

Though not a trained landscape architect, Rana designed Buddha Jayanti Park in the southern part of the Delhi Ridge with a deep understanding of the natural landscape. He took inspiration from Buddha’s final sermon: “Anything that you do has to respond to nature.”

Also read: Crackdown on old vehicles: Over 5,000 automobiles seized to curb pollution

Nehru’s encounter with Habib Rehman

While Nehru met Rana abroad, he encountered another young architect, Habib Rehman, in Kolkata in 1949. “Nehru’s direct impact on India’s modern architecture is little known. My father, Habib Rahman, had the privilege of working closely with Nehru between 1949 and 1964. Nehru greatly admired my father’s Gandhi memorial in Barrackpore, which he inaugurated in 1949, and he later arranged for him to move to the CPWD in Delhi,” says Ram Rahman, Habib Rehman’s son, a noted contemporary Indian photographer and curator.

When Nehru rejected Rehman’s Design

Nehru’s direct influence extended to the Rabindra Bhavan buildings (1961), which house the three Akademis — Lalit Kala, Sangeet Natak, and Sahitya — designed by Habib Rehman. Nehru encouraged Rehman to develop a design that drew from Indian traditions while embracing modernity. It is said that Nehru even rejected Rehman’s first design, as it resembled an office building.

Habib Rehman’s work has left an enduring mark on Delhi’s cityscape, with buildings distinguished by their modernist aesthetics and functional design. His creations, including Dak Tar Bhawan, the Zoo, Vikas Minar, AGCR building, UGC building, and R.K. Puram Sector-4 flats, reflect his distinct vision. He also designed the Mazar of Maulana Azad and was responsible for selecting US-educated landscape architect Vanu Bhupa to design Rajghat.

Both Rana Man Singh and Habib Rehman made lasting contributions to Delhi’s landscape, reflecting the spirit of Nehru’s vision for a modern India. Their unique talents, fostered by Nehru’s encouragement, continue to shape the city’s character and inspire future generations of architects.