Alam was assaulted on the night of May 25 in Gurugram as CCTV shows but there are some discrepancies in different narratives

The Jama Masjid in Gurugram’s Jacobpura is more than a century old. With a freshly painted pink edifice, it imposes itself upon the sprawling and boisterous Sadar Bazaar which is criss-crossed by narrow lanes inhabited by hawkers and vendors.

At about 10 pm on May 25, 25-year-old Mohammad Barkat Alam finished reading his namaz at the Jama Masjid and headed back to his room some 200 metres away. As he reached a well-known local sweet shop, he heard yells of “O Mulle! Ae topi wale, ruk!” When the yells got nearer, Barkat saw six men. One of them walked up to him.

“He abused me and said ‘Why are you wearing this topi? Take it off’,” Alam told Newslaundry. “I said I had just read namaz and will not take it off. He said: ‘don’t you understand what I told you,’ and slapped me. My skullcap fell and I picked it up and kept it in my pocket. You can see this in the CCTV. I shouted: ‘Why are you touching my cap? Let me go’. He said, ‘So you’ll shout at me? Now you better say Bharat Mata ki Jai’.”

When Alam protested again, he says, the man told him to chant “Jai Shri Ram” and threatened to feed him pork if he didn’t comply. “He then picked up a stick from the road and beat me. When I pushed him and tried to get away, he grabbed my kurta which tore off in the struggle. He gave me a few more blows. I started crying and then fainted. They fled in different directions and slowly a crowd gathered.”

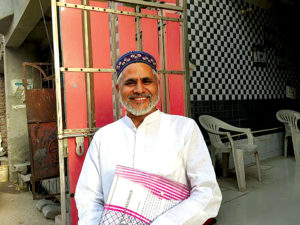

Thin and short, he has a kurta and pyjamas on, with surma around his eyes and a skullcap on his head. “From the way he abused, I could tell that he was a local,” he says.

Alam is from Begusarai in Bihar, where his brother drives a rickshaw. He worked in an L&T power plant in Khandwa in Madhya Pradesh for eight months. “I’m the only one who runs our household. I used to earn ₹5,000 every month in MP, out of which I sent ₹4,000 back home. Then I did not get any work for two months, and I went back to Bihar,” Alam says.

From Bihar, he was sent to Delhi to learn tailoring and continue supporting his family. “I’ve only been learning lately so I don’t get paid. I haven’t sent back any money yet.”

The discrepancies

Despite the details that Alam furnishes, CCTV footage of the incident makes things a little hazy.

According to the Gurugram police, the footage shows one man assaulting Alam but not the other five who he claims stood by and laughed. Gurugram ACP Rajiv Kumar told Newslaundry that a sweeper who intervened and broke up the scuffle also confirmed to the police that there was only one assailant, and he did not see others accompanying him.

Alam says that the CCTV camera is positioned such that it did not capture the five men. A sharp turn in the lane prevents the camera from recording those who stand on the left side of the camera’s field of view.

There’s a second discrepancy. The assailant did slap Alam and displace his skullcap, but he did not throw it on the ground as Alam claimed on NDTV’s show, We The People. A news report quotes Gurugram’s Commissioner of Police Mohammad Akil as saying: “It is unclear in the footage whether the cap fell but the victim has said it did, so we are going by that.”

Alam does not really see a difference between the two stories. What matters to him is that the skullcap did fall on the ground—a claim he stands by.

The third, and probably the biggest, mismatch is between Alam’s statement to the media and his FIR. The FIR does not say anything about the assailant asking him to chant “Bharat Mata ki Jai” and “Jai Shri Ram”. Alam insists he told the police everything on the same night when he was taken to the police station, including the chants, but they simply did not record it.

Newslaundry asked ACP Kumar about the mismatch. “We’ve relied on his account word-to-word and recorded the statement. And chant or no chant, we’ve included Section 153A (promoting enmity between groups on grounds of religion) in the FIR,” Kumar says. Other sections in the FIR include 147 (rioting), 149 (unlawful assembly), 323 (causing hurt) and 506 (criminal intimidation) of the Indian Penal Code.

The third discrepancy gained traction after police commissioner Mohammad Akil claimed in a press conference that Alam’s statement might have been “tutored”. When asked why the police think this, ACP Kumar points to the discrepancy between the victim’s FIR and his statements in the media. But who could’ve tutored him? Without providing a name, Kumar says it’s those appear with him in “viral videos” and have been “accused by others in the Muslim community of ‘inciting religious passions’”.

These clues point to one Haji Shahzad Khan, who runs a Gurugram-based organisation called Muslim Ekta Manch. Shahzad was the reason Alam’s story made it to mainstream media. Khan was also seated beside Alam when he made an appearance on the NDTV show We the People on May 26 after the assault.

The next day, Monday, Khan called Alam to his home in Gurugram so that he could provide bytes to media channels.

Plea for secularism

Haji Shahzad Khan resides in a small urban village in one corner of Gurugram. His verandah walls are adorned with pictures of him with smiling dignitaries. There’s also a small, old poster of the Indian National Congress pinned to a bulletin board—a collage with a smiling Rahul Gandhi and Khan himself. He says has no official links with the party but has friends who work for it.

Khan claims he is a social worker who helps not just Muslims but also Hindus who approach him with problems. He often channels their plight to the media and claims to cover legal fees for those who need it. The money, he says, comes from his construction business.

“Those who can’t help themselves, we help them. People come from Manesar and Ghitorni to meet me and seek help,” Khan says. On the table in front of us of lie letters penned by Khan that document multiple cases of harassment faced by Muslims.

A snapshot of Sadar Bazaar

Sadar Bazaar in Jacobpura is the oldest, cheapest and most crowded market in Gurugram. During the day, it’s thronged by shoppers and vendors. “The only fights I’ve witnessed here are those between the customers and the shopkeepers,” says Ram Lal, who works at the sweet shop outside which Alam was assaulted.

While the shopkeepers and traders are predominantly Punjabis, poor migrants from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar form a significant demography in this part of town. Hindus and Muslims live cheek-by-jowl and lead interconnected lives. Sanjay, for instance, runs a juice shop just outside the Jama Masjid. When I protest that the water bottle he sells me isn’t cold enough, he says it’s because he has to bring excess water bottles these days. “Inka roza hai,” he says, pointing towards the mosque, “so we bring extra bottles.”

Everyone Newslaundry spoke to in the market claims to have heard about Alam’s assault but did not witness it. Then again, the market usually wraps up by 10 pm, around the same time the assault took place.

At the end of the street where Alam was assaulted is a one-storeyed house with BJP posters and saffron flags. “The assault did take place, but it was only a drunkard brawling with another person. The rest have been spun by their people,” says a man seated outside, while another nods in agreement.

However, a paan seller near the mosque named Shaukat Ali tells me that right-wing groups create a ruckus at the bazaar’s meat market every year during Navratri. “They go up to these meat shops behind the mosque to ask them to shut down,” he says. Media reports corroborate this. The Sanyukt Hindu Sangharsh Samiti, which includes the Shiv Sena, Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Hindu Sena, is responsible for these anti-meat drives. In fact, another meat market nearby was shut down a few years ago because of a temple in the vicinity.

Both Alam and the police have established that the assailant was in a drunken state when the incident occurred. There are about six alcohol shops in the area that surrounds the mosque. While some owners beg ignorance, others say they have heard about it.

Alam appears frail and nervous, his confused countenance giving away the pressure of toeing the line drawn by relatives, community leaders, and the police. This battle of narratives has taken its toll on him. “I want to go home now,” he says. “This incident happened right after I came here. I’m now afraid. My brother says I should go back to Bihar.”

The assailant, meanwhile, remains on the prowl.

Read the full story at www.newslaundry.com