It is rare to come across a movie where every character is portrayed with so much sympathy, so much life, that their oppression does not steal them of their humanity and imperfections.

Pakistani movie Joyland, the brainchild of director Saim Sadiq, is one such gem. The movie is a result of powerful script and mature cinematic grammar. There are moments of poetic visuals, but they never overshadow remarkable social commentary of a patriarchal and homophobic society.

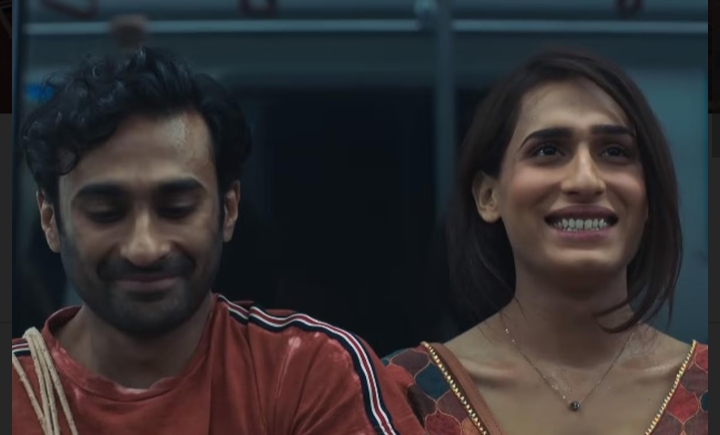

At its heart, Joyland is a story of a damaged family, repressed desires, conflicted sexuality and gender identity. Within ten minutes of the movie, we know that the story follows the lives of a lower-middle class family of Ranas in Lahore, whose patriarch Rana Amanullah (Salmaan Peer) yearns for a male heir. What unfolds within the central theme are the layered experiences of every family member, with Haider (Ali Junejo), the younger son of Amanullah, being the focus of the story. Saleem (Sameer Sohail), Rana’s elder son and another patriarch, wants a son from his wife Nucchi (Sarwat Jilani), who gives him another daughter when sex determination test goes wrong.

What is so remarkable about Joyland is its refusal to villainise any character. When Nucchi fails to provide a male heir, both Rana and Sameer do not blame her for it and there is no drama around the subject. Nucchi is never guilt-ridden because of it and Saleem loves her the same. The conversation around the son is only brought up in the family when Haider’s wife Mumtaz (Rasti Farooq) gets pregnant with a son.

The story around Mumtaz and Haider reflects how personal lives are tormented by an oppressive society and how emotions that may otherwise seem personal spring from the political nature of a community. There are no attempts to portray a definite ‘oppressor’ in Joyland, and the gloomy atmosphere throughout the movie marks the presence of society’s own imperfections, to which each person contributes. Both the characters almost feel personal, struck by dreams, desire, and tragedy.

“The beauty of Joyland is that it is not a singular narrative. In its very novelistic approach, it presents to us a basket of characters all of which are tied together by the same leash of gender and conformity. It doesn’t attempt to name things – as experiences that are so personal can seldom be named. To put an umbrella of ‘womanhood’ or that of ‘being transgender’ would be to reduce the characters and their struggles to be very one dimensional and I’m glad the film attempts to stray away from that,” says filmmaker Anureet Watta, whose movies around queer community have won international awards.

“The film is explosive, at every turn a new layer is unveiled and the characters are never looked at with pity but with dignity, as if the character has been made a close friend of the family,” she adds.

If Joyland does not villainise any character, it does not victimise them either. In Haider, we see both a victim of homophobia and a selfish man. He is not the typical ‘innocent gay man’ but also someone who puts himself first at the risk of others. When he falls in love with transgender Biba (Alina Khan), he is bothered by Biba’s decision for surgery – even when Biba sees herself as a woman. There is no hint of remorse in him for what he does to his wife Mumtaz. Yet he is portrayed with kindness, and Mumtaz (and Biba) forgive him for his conflicted sexuality because he is someone who has never spoken up, even for himself.

“It is amazing to see a script so powerful that it humanizes every character and treats them with empathy. It does not confuse political with personal, and suggests that both go hand in hand. The script speaks of so many things at once, yet does not sound complex. It is as if life itself is portrayed on the screen with its multiple layers,” says Vandana Khatri, a script writer based in Mumbai.

Another thing that makes Joyland an honest movie is its nuanced exploration of womanhood. Mumtaz is a bold and feisty woman, and in a way, someone who compliments Haider’s lack of expected masculinity. In the beginning of the movie, when Amanullah asks Haider to sacrifice a goat to test his masculinity, it is Mumtaz who takes the knife from him and sacrifices the animal when he fails to do it. Throughout the movie, when Haider does not speak for her, she speaks for herself.

Biba, the famous trans character, is someone who does not let her gender identity define her. She knows what she wants in life and she is not ready to compromise with it. She also does not sympathise with Haider to the point of harming herself, which makes their relationship more complicated and humane, and does not reduce these characters — categorically belonging to LGBTQ+ community — to mere political imagination where the personal is overpowered by the collective image of a people.

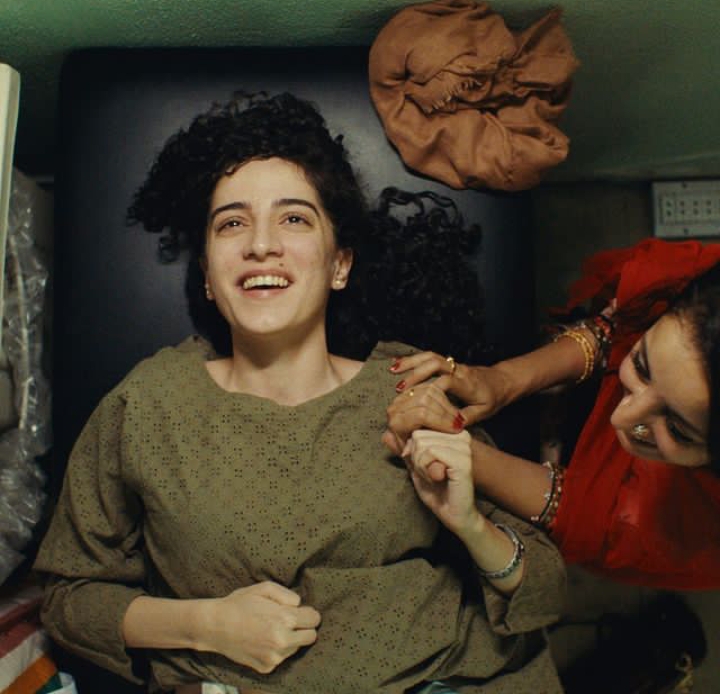

The character of Nucchi makes the movie an honest depiction of womanhood. In the beginning, she comes off as someone who is narrow-minded. It is not Salmaan and Amanullah but Nucchi who asks Mumtaz to stop working when Haider finds a job. But as the movie progresses, Nucchi is the only comfort for Mumtaz. There is no bitterness in both the characters because of the previous episode (Nucchi asking Mumtaz to give up her job).

It shows the complex ways women exist in a patriarchal society. The female friendship in the movie constantly gives warmth and hope. It is not shown as a friendship by default often marked by jealousy in the presence of a ‘dominant male’, as is typically portrayed, but an active, growing understanding of another person who exists in similar circumstances. In Nucchi, there is an existence of both rebellion and submission. She speaks up, yet never so loud, until it’s too late.

The merit of Joyland is supported by its international acclaim. It is the first Pakistani film to premiere at Cannes Film Festival and it received a standing ovation after its screening. It is also the first Pakistani movie to be shortlisted for Best International Feature Film at 95th Academy Awards and has won many international awards.

“It is absolutely amazing to see a film like Joyland, which puts such a nuanced understanding of gender at the centre of it, be appreciated at a global level. So far it has felt like, at an international level, the films that touch upon queerness are often coming from a very white and elite perspective and thus, [even] while one tries to but it is hard to find resonance with them,” says Watta.

However, the movie faced backlash from the Pakistani government and society. It was banned by the Pakistani government in November 2022 and was released after minor cuts.

“The film was fantastic but many people here didn’t comprehend it correctly. It puts light on several messages and themes, including the limitations imposed by patriarchal society, family expectations, and other issues. It’s intriguing how the film depicts individuals navigating their identity and sexuality in a restrictive environment,” says Shehzor Narejo, a film student from Pakistan.

The film is set to hit theaters in India in March 2023.