In the dusty locality of Priyadarshani Vihar, Taharpur, a straight road leads to a colony which looks just like any residential area – men cleaning their vehicles, women standing in groups to buy vegetables, and kids running around playing.

Over the years, people affected with leprosy from different parts of the country have been rehabilitated in these colonies. They have formed a close-knit community, free of any judgements or gawking.

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, is a chronic infectious disease caused by a rod-like bacteria called Mycobacterium leprae. It affects the peripheral nerves, skin, eyes and the upper respiratory tract, and causes severe nerve damage in the body. The disease is curable and early diagnosis and treatment can prevent disability.

Though India was declared leprosy free in 2005, new cases have been detected. With the intervention of new medical technologies, such cases are under control.

Out of the several ashrams in Taharpur is the Kasturba Gram Ashram which facilitates around 190 families whose members are affected with leprosy. It is located in a one-kilometre radius of the Leprosy Mission Hospital and the Rajiv Gandhi Super Specialty Hospital.

Painful journeys

Most of the leprosy patients here are old and have no recollection of how they ended up in this place. Like Chandrasar, who has been living in the ashram for 50 years, having been diagnosed with leprosy when he was 20.

Originally from Gulbarga, Karnataka, he hopped on a truck and came to Delhi, having been told that the national capital has free treatment for leprosy.

He met his wife Lakshmi* at the ashram, who had been left there with her siblings and leprosy-affected mother. “Baba was alone and it was tough for my mother to take care of all my siblings, so I married him”, says Lakshmi. They now take care of her nephew’s daughter who is studying in Class 12.

Yesbavadey, originally from Tamil Nadu and in his eighties now, sits outside his house enjoying the evening breeze. He too has no memory of how he got infected with leprosy.

Probably the oldest member in the ashram, he recollects, “I was working in a private firm in Bombay and came to Delhi with my wife and children. I had pain in my joints and ulcers, but didn’t know that it would turn into leprosy because no one knew much about the disease at that time.”

Paneer Selvam hails from a small village in Tamil Nadu and was diagnosed with leprosy at the age of 11. Selvam had a hard life in the village. He was admitted to Sacred Heart Leprosy Hospital at Kumbakonam, and against his wishes, was not allowed to continue with his studies.

Not giving up on his aspiration to study, he got admitted to a hospital in Chengalpattu, where he started a job under a medical superintendent for a monthly salary of Rs 500. He learned printing technology while staying there.

For the past 25 years, he has been living in the ashram along with his wife and three children. He met the love of his life, his wife Devi Priya, at Mother Teresa Leprosy Ashram. Her father was a leprosy patient who got admitted to the ashram, where he was in charge of a dispensary.

Devi Priya’s father wasn’t aware that Selvam, too, was a Tamilian. “When I told him I am also a Tamilian, he was very happy. He said he would like to marry Devi Priya off to a Tamilian”, recollects Selvam. “Before the death of her father, with the money I had saved, I organised everything and we got married in 1998 at a church”, Selvam says.

“Only a leprosy patient can understand the struggle of another”, said Girdhari Lal, glancing at his wife. She is from Almora in Uttarakhand. They met when he was working with a doctor in Punjab, and later became life partners, supporting each other through life’s trials and tribulations.

“She was a very sturdy woman, from the hills”, added Lal with a smile on his face. She was diagnosed with leprosy very late when her eyes started to droop. She used to work in the fields, but with leprosy, heavy work caused visible damage to her hands.

Lal is the secretary of another colony in Taharpur. He was diagnosed with the disease when he was studying in Class 8 when doctors visited his school for a checkup. He didn’t have any deformity and was diagnosed in the nick of time. He relocated to Punjab, where he had to undergo surgery on his leg. Lal returned to Delhi in 1978, intending to make his daughter an IAS officer.

Stellar role of NGOs

Sasakawa India Leprosy Foundation (S-ILF) provides livelihood, education and skill training in an attempt to restore the dignity to those affected with leprosy. “The initiatives which have to be done by the government are now done by these organisations”, says Lal.

Before the interventions and rehabilitation, leprosy sufferers used to beg on the roads, displaying their disabilities to evoke sympathy. However, help from the community and NGOs has helped many stand on their own feet.

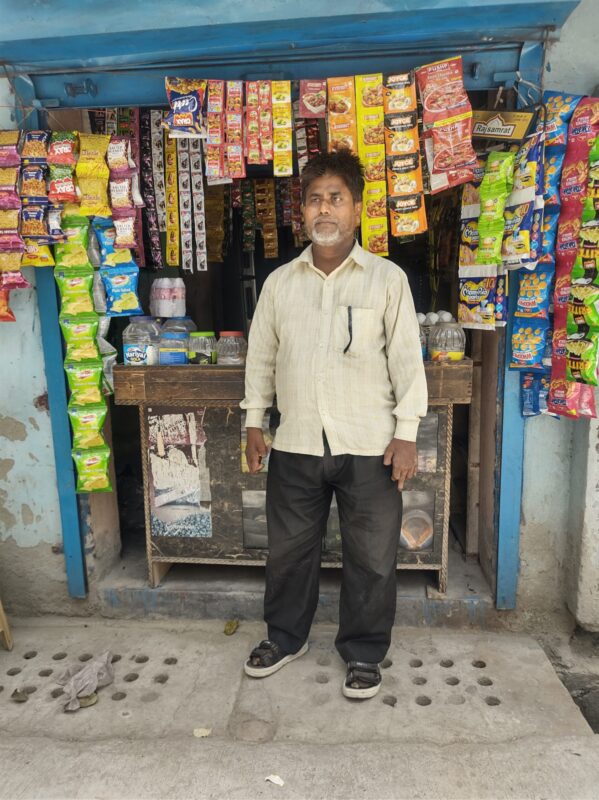

Parvez Alam owns a small general shop in the colony which was an initiative by S-ILF. It is his only mode of income apart from the pension for handicapped persons. He says he got infected with leprosy as a reaction to the black fever medicine, after which he made two attempts to end his life.

He came to Taharpur after he had a severe injury to his leg while herding buffaloes. After getting his leg treated, he started riding a cycle rickshaw to make ends meet. But for the last two years, the shop has been his sole source of earning a livelihood.

Akash* is a CA student who is receiving a scholarship from S-ILF. Both his parents are leprosy patients, and his mother works in a school to run the family. But he wasn’t confident enough to disclose to his friends earlier that he was residing in a leprosy colony.

He says, “I never disclosed my address to my friends when I was in school because of the fear of judgement. Now, I am more confident and my friends know where I come from.”

One of the S-ILF staff said that when they used to send letters to their students staying in the hostel, they asked them not to write their NGO’s address on the envelopes.

“The situation is changing now, but more awareness and interventional programs are necessary to make more changes in the society”, the official said.

In need of security

The leprosy patients are given a monthly pension of Rs 3,000 by the Department of Social Welfare. Under the Rehabilitation Centre for Leprosy Affected Persons (RCL), persons cured of leprosy – who are categorised as disabled people – can avail of the pension based on the eligibility criteria.

“The problem is that though there are these pensions, many are not receiving them”, said Selvam. “How can we manage to live solely on the amount given by the government?”, he questions.

Those who are handicapped are only eligible for the pension of Rs 2,500 under the general category and not the RCL pension.

“We have children who depend on us, we have to take care of their schooling and fees. Apart from the pension, there is no help from the government for our children”, Selvam adds.

He further said that he, and others like him, can somehow manage schooling, but college education and fees are unaffordable. Even after completing their studies, many offspring are not able to pursue careers.

Stigma related to leprosy still prevails in society. It often surfaces during the time of admissions. “Certain schools don’t allow admissions, saying that we do not come under their area when we clearly are. It’s just that they don’t want students coming from this background”, says Selvam.

There are several non-profit organisations and mission agencies which help in providing free education in Noida. “It’s better for the children also, they’ll get an education which we can’t provide. They were enrolled from the age of six. Were allowed to visit the children only once a year, so that other students studying there didn’t get disturbed”, informs Lal.

Another issue faced by the leprosy rehabilitators is land ownership. They have been relocated to these ashrams by the government, but none of these houses are under their name. They live in constant fear and insecurity as they have no legal rights on the land.

Lal says, “We have been fighting since 2016 to get these plots under our name. We have talked and sent letters to all the officials, and until now, there have been no initiatives.” Talking about his sole request to the government, he says, “The next generation should not suffer like us, they should be given ownership to the property after our death.”

For more stories that cover the ongoings of Delhi NCR, follow us on:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/thepatriot_in/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Patriot_Delhi

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Thepatriotnewsindia