Almost every aspect of the Central Vista redevelopment plan – its very need, cost, clearances, public consultation – is contentious. But the government is pressing ahead with it even as the Coronavirus pandemic ravages the world

On 20 March, a few days before Narendra Modi put India on lockdown to contain the Coronavirus outbreak, his government changed the law for use of around 90 acres of land in the heart of New Delhi. Reason? To pave the way for redeveloping the Central Vista.

The project, which includes the building of a new Parliament and a house for the prime minister, is estimated to cost Rs 20,000 crore. That the Modi government is pressing ahead with it even as India is battling unprecedented health and socioeconomic crises has sparked criticism, with political leaders and activists demanding that the money instead be used to alleviate the suffering of the poor and marginalised citizens bearing the brunt of the Coronavirus pandemic.

In a letter to Prime Minister Modi and housing and urban affairs minister Hardeep Puri, 60 former civil servants called the Central Vista project an “irresponsible” move at a time when enormous funds are required to strengthen the public health system”. “It seems like Nero fiddling while Rome burns,” they concluded.

But controversy has dogged the project ever since it was unveiled in September last year. Critics have questioned the lack of transparency, the cost, the hasty approvals, the absence of proper public and expert consultation, even the very need and moral justification for it.

The Modi regime claims the buildings erected by the British Raj that house India’s government and legislature are past their use by date and need to be urgently upgraded. But the secretive manner in which it has pushed through the project has cast doubts that it’s driven solely by utilitarian imperatives. One accusation is that it’s Modi’s “vanity project” to leave behind a legacy; another is that it’s a gravy train for builders and babus allied with the regime; yet another is that it’s a capture of the commons by the elite.

However, mostly because discussions about the project are centered on specific aspects — cost, loss of public space, the selection of the architect — the full picture has become hazy. Seen from a wide angle, what does the Central Vista project entail? How will it change one of the city’s most iconic public spaces? Did it go through the proper processes of approval?

Newslaundry examined official records and spoke with urban development experts, government officials, and architects to draw a detailed picture of the scope and import of Modi’s pet project.

Central Vista

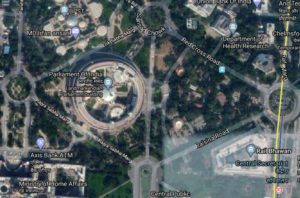

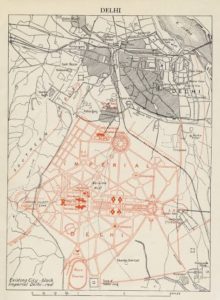

The Central Vista is a 4-km stretch from the Rashtrapati Bhavan to the India Gate in Delhi. Built by the British Raj in the first half of the 20th century, it is designed as an expanse of open, green space surrounded by various offices of the central government, the parliament house, monuments, and museums.

Redevelopment plan

On December 21 last year, the Delhi Development Authority, tasked with managing and developing public land in the city, issued a notice proposing to change the use of 90 acres of land in Zones C and D of the Delhi Master Plan 2021 from “recreational open spaces” to “government offices”.

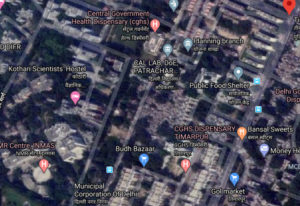

Zone C is also called the Civil Lines Zone and includes the Old Secretariat Complex, which houses Delhi’s state Assembly, and the Civil Lines Bungalow area of the colonial period. It also houses Roshanara Bagh and Qudesia Bagh from the Mughal period.

Zone D, also called the “protected zone”, mainly comprises Lutyens’ Delhi and its extensions, save for the Lutyens’ Bungalow Zone. This is where the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Central Secretariat, Supreme Court, Delhi High Court, Parliament House, and India Gate are located. Zone D also includes public parks and recreational sites such as the Delhi Flying Club, National Stadium, Delhi Polo Club, Race Course, Pragati Maidan, Buddha Jayanti Park, and Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium.

The DDA’s proposal was certified by the Modi government through its 20 March notification, which changed the use of 3.9 acres of land in Zone C and 86.1 acres in Zone D. Of this, 24.5 acres were reserved for recreational use and 65.5 acres for “public and semi-public facilities” such as government offices, places of religious gathering, centres of education or culture, and hospitals. Now, 80.52 acres will be at the government’s disposal and only 9.54 acres will be reserved for the public.

The redevelopment project involves Plot 8 in Zone C as well as Plots 2 to 7 in Zone D. According to the notification, Plot 8 is government land near Timarpur on Lucknow Road. It will be developed into a recreational district park.

Plot 2 opposite the Parliament House is a recreational park for the public. Here, the new triangular parliament building will be erected.

Plot 3 is south of Dr Rajendra Prasad Road and encompasses the National Archives, the custodian of India’s official records and South Asia’s largest archival repository. It will be modified to build government offices on around 5.88 acres and a park on 1.88 acres.

Plot 4 is between Dr Rajendra Prasad Road and Janpath. It’s the site of the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, which will be demolished to construct office blocks on 22 acres and a park on 1.88 acres.

Plot 5 is east of Man Singh Road and south of Ashoka Road. It is where the Ministry of Defence is housed in Raksha Bhawan. The plot is earmarked for government offices.

Plot 6 is north of Maulana Azad Road and east of Janpath. The plan is to pull down the assortment of existing buildings on the plot, and build office blocks on 22 acres of it and a park on 1.88 acres.

Plot 7 is north of Dalhousie Road near the South Block. Its use has been modified from “recreational play area” to residential area, most likely to build a new house for the prime minister.

Controversially, the DDA’s notice for changing land use came nearly three months after the Modi government had issued a tender for redeveloping the Central Vista. This means the government saw the process of land change and all that it entails – public consultation, for one – as a mere formality.

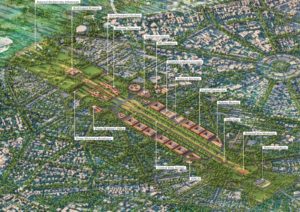

The tender, issued by the Central Public Works Department, or CPWD, in September 2019 and inviting bids from national and international architects, stated that the aim was to “replan the entire Central Vista area from the gates of Rashtrapati Bhavan up to India Gate”. The focus, however, would be on constructing a Parliament building by 2022, redeveloping a “common Central Secretariat” by March 2024, and upgrading the “public facilities, amenities, parking, and green spaces of the Central Vista to make it a world class tourist destination by November 2020”.

As to why the Parliament House and the Central Secretariat needed to be replaced at all, the tender listed many reasons from “acute shortage of office space” to inefficiencies of the structures to “difficulties in coordination” among ministries.

The job of overseeing the redevelopment project was entrusted to the Central Vista Committee, originally constituted in 1962 “to advise the government in the development of the Central Secretariat Complex and the Central Vista”.

The committee approved the project in a meeting on April 23 where none of its non-government members from the Indian Institute of Architects and the Institute of Town Planners were present. What was the hurry to clear the project in the absence of the outside experts?

“The importance of the project in the nation’s interest and the timescale for its implementation,” the minutes of the meeting stated by way of an explanation. Rather egregiously, the minutes didn’t record any discussion about the project.

Balbir Verma, who represents the Indian Institute of Architects in the Central Vista Committee, was not convinced. “Such an important meeting to consider the proposed designs for the Parliament building – which happens maybe once in a hundred years – was held in the absence of all non-governmental external experts under the guise of urgency by ignoring the request for postponement of the meeting for a few days until lockdown restrictions had been lifted,” he complained. “What is the point of having experts on your panel when their opinion is not being sought on such a historic project?”

Khan Habeeb Ahmed, president of the Indian Institute of Architects, would not take questions on the Central Vista project.

The developer

The CPWD tender specified that only firms that had worked on projects worth over Rs 100 crore could bid for the Central Vista project. In addition, they were required to have worked in India for at least 10 years and be able to deposit earnest moneyof Rs 50 lakh. The chosen company would be paid Rs 229 crore for its services.

Just seven weeks later, on October 25, the tender was awarded to HCP Design, Planning and Management Pvt Ltd, based in Gujarat. It was chosen out of six firms by a panel of town planners, engineers and architects formed by the CPWD.

Immediately, eyebrows were raised. The tender wasn’t open per se, one of the main accusations went, because its specifications were tailored for large architectural firms that had worked on a Master Plan.

“The opaqueness in this project is in stark contrast to the IGNCA competition,” noted Anuj Srivastava, a retired army officer who teaches at the School of Planning and Architecture in Delhi. “Then, the International Union of Architects monitored the design competition and it was judged by an international jury. Here, the process was rushed. Eighty percent marks were given on the basis of a technical presentation that was just a concept. The entire process was flawed.”

The IGNCA is widely considered an example of a democratic urban design process.

The Modi government’s handling of the Central Vista plan also diverges greatly from how it went about erecting the National War Memorial and the National War Museum close to the India Gate. The cabinet approved the project in 2015 and a multistage global competition was held in 2016-17 to pick the architect. Construction did not start until necessary consultations had been held with the capital’s urban bodies and a detailed project report prepared. This was done even though the project didn’t entail largescale demolition of heritage architectures like the Central Vista project does.

Still, the Delhi High Court pulled up the government, observing that every building site depicted what was being built, but the construction at the India Gate was being carried out in a secret manner behind “big walls”.

Considering all this, the government should “press the pause button” on the Central Vista project, argued Srivastava. “The entire process needs to be restarted,” he said. “There has to be an examination of its urban design aspects, the necessity of the project, and expenditure.”

It hasn’t helped the government’s case that Bimal Patel, head architect of HCP Design, has given differing ideas of what the plan entails. In an interview with the Indian Express in January, Patel said, “As we go around making this major change, we will try to do it in a way that it is not a rupture with the past. What we are trying to do is to respect history, perhaps even strengthen the original intent by using architecture to strengthen the original diagram.”

The following month, in a presentation at the CEPT University, Ahmedabad, where he is the president, Bimal took a different tack. “If we look at Central Vista today,” he said, “it is disorderly and incoherent, particularly in the flanks.”

His plan, Patel suggested, was to bring order and efficiency to the Central Vista. The redevelopment would also be a “commemoration of 75 years of India’s independence”.

On March 12, delivering a talk on “Modernising Indian Cities” at National Firms Archives in Pune, Patel said the redevelopment plan had evolved over the previous months. In an earlier sketch of the plan, the chambers for MPs, IGNCA, Central Conference Centre, National Diversity Arboretum and the vice president’s had not been marked.

As per the latest plan, once all their work is complete, Falguni Budhraja of HCP Design explained in an email to Newslaundry last month, the Central Vista will have a new Parliament House, new residences for the prime minister and the vice president, Prime Minister’s Office, chambers for MPs, a Common Central Secretariat housing all union ministries, a Central Conference Centre, and a National Biodiversity Arboretum. The North and South Blocks — which house the PMO and the ministries of home, defence and finance — will be converted into museums. There is a slim chance of a path being laid from the National Stadium to the Yamuna river.

Project cost

Questions about the total cost of the Central Vista project were asked in the Rajya Sabha on 19 March, and in RTI applications but the government has refused to reveal it. According to the Print, however, the government has allocated Rs 20,000 crore for it. For perspective, that is as much as Kerala plans to spend to ease the economic hardship caused by the Coronavirus outbreak. India’s total allocation for the health sector, at Rs 67,111 crore, is just a little over three times as much.

The CPWD, which oversees the project, saw a three-fold rise in its budgetary allocation this year to nearly Rs 3,033 crore. That the allocation for the redevelopment plan does not show in its budget, however, has raised questions.

Madhav Raman, an architect and urban planner, explained that once money is allocated to a ministry in the annual budget, the minister sanctions its use for different projects. The sanction is granted either on the basis of detailed project reports and feasibility studies or on the central cabinet’s collective and informed decision.

“The ministerial allocation of Rs 20,000 crore does not seem to have yet happened,” he said. “The project budget, which is essentially being prepared by the consultant, has not been framed. Every CPWD or housing affairs ministry tender has an estimated project cost that is publicly displayed on the notice inviting bids. That’s missing here.”

Key concerns

Concerns about the Central Vista project span almost all its aspects. But the objections that have gained most attention relate to the violation of the law change use law and the grant of clearances without public consultation, absence of expert input, and the need for a project that the critics argue would squeeze out common folk from the heart of the capital.

The 18 May letter by the civil servants raised many of these objections. The project, they pointed out, would irrevocably destroy precious heritage, cause severe environmental damage, and rob the public of recreational spaces. Moreover, the former bureaucrats noted, the plan wasn’t offered for public consultation or expert review.

Referencing the letter, the National Alliance of People’s Movements, a coalition of progressive organisations and movements, on 20 May demanded the withdrawal of the environmental clearance granted to the project. It claimed that the union environment ministry’s Expert Appraisal Committee, tasked with granting green clearances, hadn’t adequately considered the 1,300 or so objections submitted to it about the “ill-conceived” project.

The NAPM also argued that the project violated Unesco’s 2003 “Declaration on the Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage”, to which India is a signatory.

The DDA’s December 2019 notice had invited objections, to be filed within a month, to its proposal for changing the use of 90 acres of land. It received 1,292 objections, the gist of which was that the need for the project wasn’t established beyond reasonable doubt, that the environmental damage would be too high, and that demolishing heritage buildings was unnecessary.

But opposition to the project had been growing well before the DDA issued the notice. In November 2019, a group of architects, urban planners, lawyers, and activists opposed to the demolition of heritage buildings formed a collective called LokPATH. It built enough pressure to force a change in the redevelopment plan restricting the demolition to the National Archives; National Museum; IGNCA; Jawaharlal Nehru Bhavan, which houses the foreign ministry; and Rail Bhavan. In the first plan of HCP Design, several other heritage structures such as the North and South Blocks and the Parliament House were marked for destruction as well.

The critics reject the government’s claim that the structures set to be demolished are too old and inefficient for contemporary use. The Jawaharlal Nehru Bhavan, they point out by way of an example, was completed just about two years ago. Rail Bhavan spent nearly Rs 50 lakh only last year to install a rainwater harvesting system. Several other buildings such as Shastri Bhavan and the IGNCA have similarly been renovated and retrofitted in recent years, at considerable expense to the taxpayer.

“The Central Vista redevelopment project will recreate this space into a barricaded zone. The recreational, open spaces where government officials can be seen lounging around in the evening will be decreased,” said Rajeev Suri, an environmentalist and urban governance activist, who is fighting the project in the Supreme Court. “The living heritage, which is a source of our pride and nationhood, will be completely wiped out.”

In his petition, filed on April 9, Suri denounced the government’s March 20 notification as a “brash move” that would rob citizens of “a vast chunk of highly treasured open and green space in the Central Vista area available for public, semi-public, social, and recreational activity.” This, he argued, violated Article 21 of the Indian Constitution which guarantees the right to life, “the right to enjoyment of a wholesome life”.

Suri had already challenged the DDA’s notice changing the land use in the Delhi High Court. A similar petition had been filed by Anuj Srivastava. Justice Rajiv Shakdher took up their pleas on February 11 and directed the DDA to inform the court before notifying changes in the Master Plan.

In response, Hardeep Singh Puri declared that the government would not allow the project to be “derailed” and insisted that it was entirely transparent.

“It was not a stay. It did not restrain them from doing anything except they couldn’t do anything without informing the court,” Suri said of the high court’s direction.

Still, the government felt “fairly constrained” by the direction and moved an application before the high court’s chief justice.

The next day, the CPWD sought environmental clearance for the new Parliament House, which it said would cost Rs 776 crore and take 12,700 workers around 260 days to build. The “tentative cost” has since been increased to Rs 922 crore, with the CPWD claiming it was necessitated by “modifications in the concept plan”. Again, the change was made without the public being informed.

On February 25, the high court asked the central government and the CPWD to respond to Srivastava’s plea that trees must not be cut to build the new Parliament House. In response, the Expert Appraisal Committee deferred the decision on granting the green clearance to the proposed building.

Three days later, however, a division bench of the court gave relief to the government, saying the DDA need not inform it before notifying changes in land use. The order was passed without hearing the petitioners.

“The court could easily have served us a notice to appear within 48 hours or so but they decided not to,” Suri complained, adding the ex parte order removed the “little protection” provided by the single bench. He explained that the particular clause that directed DDA to inform the court before making any changes was removed.

Suri challenged the order in the Supreme Court, describing it as “bad in law”. “The big argument from the bench at the Supreme Court was to appeal in the same court that had given the order,” Suri said. “We didn’t want to go back since the high court was not going to change their mind on an order that was blatantly in favor of the government. Somehow, we managed to convince the Supreme Court that this matter should be heard by them.”

On 6 March, the Supreme Court invoked “larger public interest” to transfer all pleas regarding the Central Vista project to itself.

The pleas filed by Suri and Srivastava were to be heard on March 18 but that did not happen because of the coronavirus outbreak.

Suri’s other petition, filed in the Supreme Court on April 9, was taken up on April 30. At the hearing, Solicitor General Tushar Mehta asked, “Parliament is being constructed…Why should anyone have any objection?”

So, what has this legal battle achieved so far? “When the high court dismissed the plea and the matter went to the Supreme Court, the previous standing basically became status quo,” said Rajiv Bhakat, an architect and an urban designer. “The previous standing was that there should have been a change in the land use order for that piece of land which is exactly what was being contested in the high court.”

“Basically,” he added, “it gave the DDA the privilege to go ahead and change land use while waiting for the courts to reopen.”

This scenario only favours the government and its agencies which have often employed the doctrine of fait accompli to achieve their aims, Suri argued. “You brazenly do something,” he said, explaining the doctrine, “and then you say we have done it, ab jo penalty dena hay de do.”

On the ground, this manifests in many ways. The DDA, for one, is required by law to consult the public widely before changing the use of land, but it has often disregarded this norm, in spirit if not in letter. The CPWD and the Expert Appraisal Committee have similarly drawn wide criticism for violating rules and processes.

In 2016, a Rs 32,885-crore plan to redevelop seven colonies in the city under the DDA’s housing scheme was pushed through without consulting the public in any meaningful way. For the same project, which involved felling at least 14,031 trees and was overseen by the CPWD, environmental clearances were granted allegedly in violation of the rules. Similar was the case with the East Kidwai Nagar project, which cost an estimated Rs 5,000 crore.

In the years since, legal battles have revealed irregularities in both the projects, from the way approvals were obtained and environmental impact assessments done to how the Master Plan 2021 was violated.

Similar violations have marked the Central Vista project as well.

The DDA held the mandatory public hearing on the project in early February. “It was a sham,” alleged Narayan Moorthy, an architect in Delhi who participated in the proceedings. “Usually, the DDA conducts hearings with all objectors in a large hall. But this time they seem to have purposely called just 20-30 of us at a time for an hour each,” Moorthy explained. “We calculated that since 1,292 people were dealt with over two working days, each of us got two and a half minutes. Is that enough time for something this complex? Obviously, it was a sham exercise. If it were a real public consultation, we would have been able to ask questions and the DDA would have given us answers. Here they refused. They said their job was merely to record our objections and convey them to the appraisal committee. And they didn’t allow the objectors among us to record the session either. When one of us asked if we could get a copy of what they were writing down, he was refused.”

Moorthy complained that they were given barely a day’s notice to appear for the public hearing and that it was conducted in “a mechanical manner with no rationale given for the change of land use”.

In effect, he noted, “this means a bureaucrat sitting in his office will now decide and that’s going to be our reality. We can’t even go there and say that no, please don’t do this.”

If that wasn’t enough, a day before the March 20 notification was issued by the government, the DDA suspended all public hearings with “immediate effect till further notice” in view of the coronavirus pandemic.

Still, the Expert Appraisal Committee went ahead and approved the building of the new Parliament House in a meeting on April 22-24. It justified this claiming that the old parliament building was in “dire need” of retrofitting.

How the committee deals with clearances for other buildings in the Central Vista project remains to be seen. In recent weeks, it has cleared major projects in video conferences without having its experts conduct field visits and listen to the concerns of the affected people.

In the Central Vista project, though, the “primary issue” relates to the use of public space rather than green clearances, argued Moorthy.

“India’s early planners, in 1962, reserved for the public some plots that the British had earmarked for government offices, thus strengthening the vision of this being the people’s space. Two-thirds of Rajpath and the hexagon around India Gate was acquired and the erstwhile princes’ palaces there transformed into sociocultural centers for the public. This is where the National Gallery of Modern Art and the Patiala House Courts stand today,” he said. “The idea was to give back the centre of Delhi to the citizens. When an Indian thinks of his country, the picture that probably comes to his mind is that of India Gate, Rashtrapati Bhawan, North Block, South Block. It’s sad that a democratic government of India is doing worse than what even the colonialists did. A colonialist such as Edwin Lutyens still left space for the public. Today, they are putting up government buildings on the whole space.”

Pawan K Shrivastava, the maker of such films as Naya Pata and Life of an Outcast,gets what Moorthy is talking about. “A city is made by the memory of its people, by the nostalgia they attach to it,” he said. “Public spaces have people’s memories attached to them. If you go to India Gate at night, you see people having brought homemade food in these spaces. There are traditions attached to these spaces. If the government encroaches on them, they seize away an important part of people’s lives.”

He recalled shooting his first film near India Gate. “People are able to relate to the landscape,” he said, by way of an explanation. “The cultures attached to this land should be preserved and protected.”

Along with Moorthy, Srivastava also attended the public hearing on the Central Vista project. “There were some DDA officials and some representatives. Their names were not written anywhere, so we asked a few of them,” he said. “They said the hearing was not a question and answer session and they would not be giving a response.”

Instead, the officials videographed the session and noted down the objections and suggestions. “We came away with the feeling we were not given a proper hearing. They could just listen to the objections, disagree with them, and carry on with it.”

That’s when Srivastava decided to move the high court. “Central Vista is no more British than the English I am speaking,” he said. “Change is an evolutionary process, but to indulge in largescale demolition and construction in such an iconic area of heritage is against all norms of conservation.”

He rued that the DDA was going ahead with changing land use “despite concerted and informed opposition”. “Change in land use has to be carried out with due deliberation for a particular reason, it cannot be based on an architectural firm’s design,” he added. “Change of land use was the first concrete step that the government took with regards to this project. A change is only supposed to happen when there’s a need felt for it. In this case, the sudden change from open, public and semi-public usage of spaces to government offices is not justified. An authority need not given a reason but when such a large portion of land is involved in a heritage area, there should be a reason for it.”

That isn’t all. Moorthy pointed out that the DDA’s 2019 notice also made modifications to the Transit Oriented Development Policy of the Master Plan 2021. The policy is aimed at optimising the use of land in the city by planning housing complexes and workspaces in a way that reduces traffic congestion, thereby creating “walkable, livable and breathable spaces”.

That doesn’t sound so bad, right? Well, as Moorthy explained in an article in the Wire, the modifications remove the protections given to preserved historic zones such as “the Central Vista, the colonial leafy environs of both the Lutyens’ Bungalow Zone and Civil Lines, and the Walled City of Shahjahanabad”.

LokPATH has since raised objections to these modifications in a complaint to the DAA.

Newslaundry reached out to Puri as well as officials of the DDA and the CPWD for comment, but none of them responded. The report will be updated if a response is received.

www.newslaundry.com