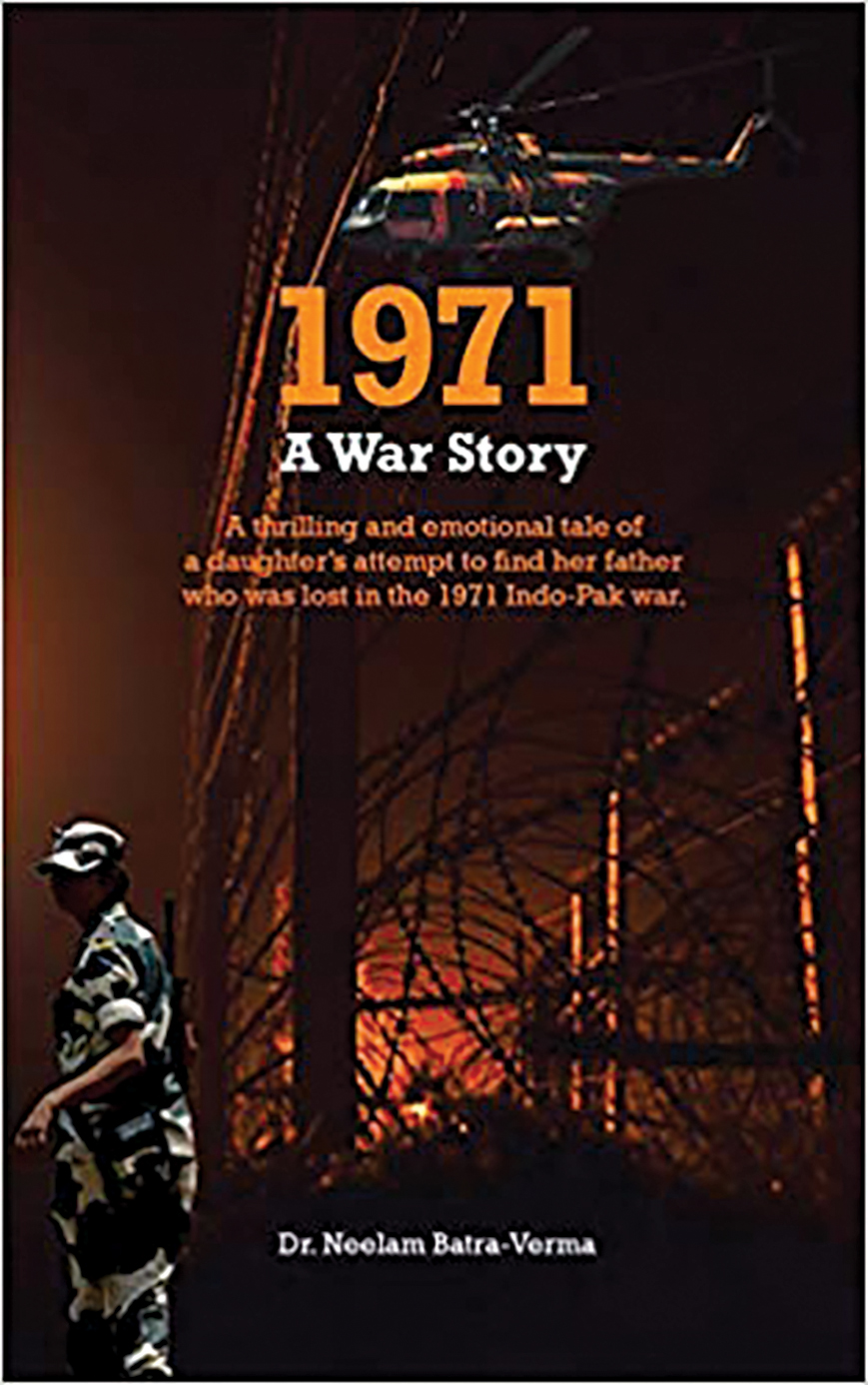

When a soldier goes Missing in Action, only families seem to care. A fiction based on this searing fact

This work of fiction is based on facts – in fact, it was inspired by the author’s meetings with families of defence personnel who went missing in the 1971 Indo-Pak war. It was propelled by her anguish she felt on learning that neither of the neighbouring countries’ governments paid much heed to the pleas of the families that their beloved sons were languishing in Pakistan jails.

The protagonist is one such wife, who lives like a widow yet believes that her husband, a pilot with the Indian Air Force, will come home one day. Anita’s childhood is recreated with loving detail, giving today’s reader a glimpse of what life was like in the old days. As in:

Minister Indira Gandhi had announced that every village would have at least one television set so all villagers could get together and watch in a community hall. The villagers had asked the pradhan (headman) to send an application to the state government. But since Shikha’s family had allowed everyone who wanted to watch the Sunday movie, no one really cared much. Shikha’s father Babu Ram would take out the television on the verandah of the house and open the main door. People would bring their own mats to sit on, while children would just sit on the bare ground. There would be pindrop silence in the village when the film was on. Only the occasional moo of a hungry cow or the bark of stray dogs could be heard till 10 pm when the film ended.

It would also amaze the present generation how hard girls had to fight to go to college, especially in rural Punjab. The spectre of marriage hung over every girl’s head right from her teenage years, as if their lives would only start once they were hitched to a man, which seems ironical when they became widowed at an early age, either due to disease or war. Young girls would barely know what the real world outside their homes was like before being plunged headlong into events beyond their control. It happens, in this book, with three girls who are the best of friends but whose inchoate dreams are shattered as they sink into lives of quiet despair and emotional deprivation.

The book tries not to demonise Pakistan in the usual cliched way that an enemy country is usually described. There is a couple on the other side who helps Anita’s daughter in her quest (see extract). However, the descriptions of life in Pakistan are close to the bone, especially in the way a woman wandering around alone is treated. The inevitable happens, but it happens in a place where human rights are supposed to be protected, not violated.

However, the real aim of the author is to hit out at the indifferent attitude of the politicians and military bureaucracy. There is a lecherous army officer who is not squeamish about propositioning a pregnant woman. There is an association of ex-servicemen formed to trace 54 missing defence personnel of the Bangladesh war. But it does seem that there is an astonishing gap in understanding between the armed forces and people in general. The former are prepared to sacrifice even their lives to defend the borders but society does not spare even a thought for the families of those who go Missing in Action. If the book bridges this gap, it would be a worthwhile reward for such a heartfelt enterprise.

Extract:

After all security formalities had been completed, Salim started chit-chatting with the jailor as if they were long lost friends. Parveen Ahmed, a big thickset man with a small goatee, was the very epitome of a god-fearing man who valued his service to his country – his only goal in life. They were served tea and biscuits, a rare occurrence. While Aju merely nodded as the conversation meandered around Salim’s difficult cases, which included looking for missing persons, Sultana’s humanitarian efforts, the weather and finally the political situation in Pakistan. “There is simmering tension between Nawaz Sharif and Pervez Musharraf after Kargil. Pakistan had to withdraw because of the Prime Minister. Musharraf thinks if they had the political backing, things would have been different,” Ahmed was saying.

“Kya pata, Mian,” Salim said casually, sipping his tea. “One cannot clap with one hand. Prime Minister has to bow to international pressure. We know that Clinton was so mad at Nawaz that he refused to meet him at the White House. In fact, Washington did not invite Sharif Mian to visit. He went on his own, as he was scared that there might be another military coup. I read somewhere that Clinton was mad at Pakistan for having started the war, which could turn nuclear anytime.”

“But Clinton could have asked India to withdraw too,” continued Ahmed.

“Why would India have withdrawn,” countered Sultana. “India was winning the war militarily. They were on safer ground. Had we not withdrawn, India would have killed so many of our soldiers or the mujahideen, whatever India calls them.”

“India can say what it wants. But in the end, it was our soldiers’ morale that went down,” said Ahmed.

“Had Pakistan not bowed to Clinton pressure, the United States had threatened to shift its historic alliance with Pakistan publicly towards India, which would be a big blow on our economy and reputation,” said Salim.

Aju had merely nodded at the conversation, doing her best to stay calm and not arouse suspicion at the portrayal of India as a villain. Finally, they were escorted inside the prison. Aju looked around the sprawling ground and high brick walls, with so many people crammed inside like stuffed dolls. It was very noisy, with guards patrolling the area. “We don’t keep Indian prisoners with the locals,” the jailor was saying. “Sometimes local convicts read the news and attack them. We have to be careful.”

Aju knew the jailor was lying. It was not only the convicts who beat up Indian prisoners, but the staff themselves was known to treat Indians like animals. She had read and heard about the treatment meted out to Indian prisoners in this and other jails of Pakistan. Political enmity prevailed inside the high walls big time.

“For how long are the Indian people kept here?” Aju asked.

“It depends. Till the time the court sentences them, depending on their crimes. The rule is, once they have served their sentence, they cannot be kept here. We have to send them back to India,” the jailor informed.

“Is every person who is arrested produced before the courts?” Sultana asked.

“Of course,” the jailor said proudly. “That is the law.”

As fact mixes with fiction, a very believable scenario is painted of survival in enemy territory as part of a nomadic tribe.