With the law decriminalising suicide coming into effect on May 29, those who are depressed will have a better shot at coming out in the open and seeking help

It was as early as the age of three that Sanchana Krishnan’s parents noticed how she struggled to sleep at night, talking to herself, trying to make herself feel better. Now almost 25, she says that she vividly remembers being terrified of the dark, sometimes struggling to sleep — a paranoia that persists.

By eight, her mother had decided to take her to a therapist, for which she received a lot of flak from the family. It was only when the Internet entered their household that Krishnan began figuring out what was going on. “I learnt that people can actually understand minds,” and that she could learn about it too by taking psychology. In 11th grade, when she did, Krishnan came across bipolar disorder and saw how it related to her own self.

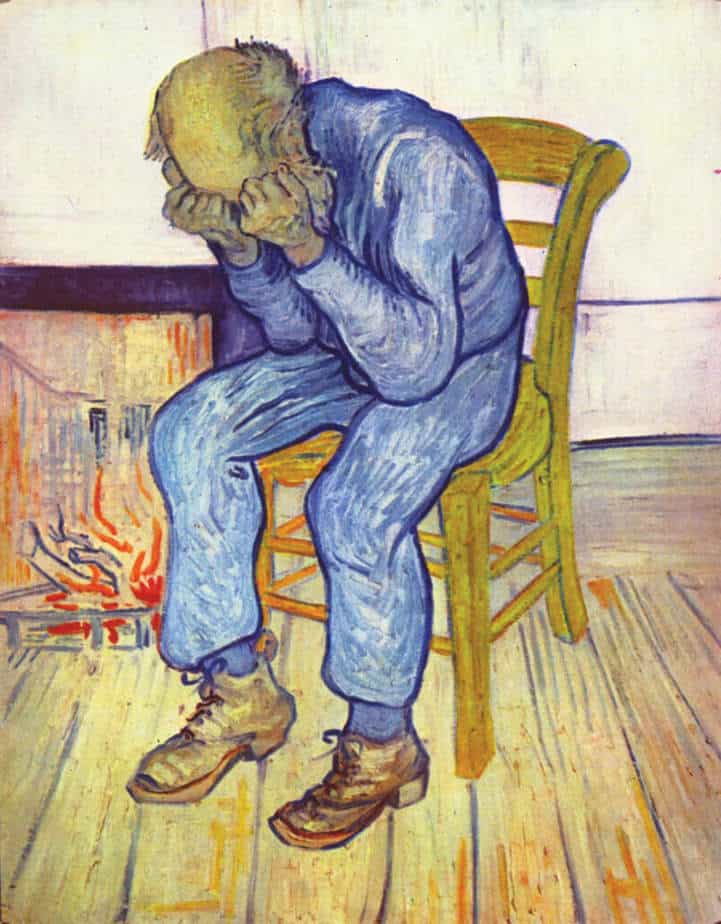

“It gets exhausting, you sometimes wish to be like everyone else; I have to pick myself up all the time.” Expressing just how it is to live with bipolar disorder, she candidly points out: “When I get depressed, my tendency to self-harm happens. Medication makes me numb, and I get scared of its effects. Sometimes I overdose and knock myself out for some time”.

For now, she’s making the most of her own experience and understanding of people’s needs with a mental health advocacy group she started called Okay, Not Okay. Krishnan says “no one should struggle in silence” and that this group would provide people help, “empowering them, so they don’t feel victimised.” Because if you don’t talk about your problems, as Krishnan puts it, “You’ll stew in your own soup.”

And that’s also one of the things which the new Mental Health Care Act of 2017, which came into force on May 29, will do. The fact that attempt to commit suicide is now decriminalised will allow people to speak up, Krishnan believes. India was amongst the very few countries that could, under law, sentence someone to a year’s imprisonment or fine, or both, for taking the extreme step of attempting to kill themselves. This in itself, she says, was evidence that the government stigmatised mental health.

Vikram Patel, a leading researcher on mental health and professor at Harvard and London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, reiterates that the amended law will allow people to seek help without any fear. It is also “a recognition by the government that mental illness is not voluntary”, Patel adds. The earlier Act of 1987 focused on protecting people from those that were mentally ill. Now it’s about “enshrining care to those living with mental illness” and give them “freedom from discrimination”.

Patel, who won the 2014 Sarnat Prize for his contributions to improving mental healthcare in developing countries, had revealed the burden of mental disorders in low- and middle-income nations and showed a strong link between mental disorders and poverty.

There is still a huge gap in resources available to those living in rural areas — where they can often face discrimination. Dr Johann Alex Ebenezer, a psychiatrist who extensively worked in rural areas of Madhya Pradesh, said that the resource crunch was acute. There was shortage of medicines, and he was the lone psychiatrist in four districts with 75 villages.

India has at least 50 million affected by mental health problems. In sharp contrast, there are 0.30 psychiatrists, 0.17 nurses, and 0.05 psychologists per 1,00,000 mentally ill patients.

One solution to counter this dearth in the rural set-up could thus be the promotion of non-specialist healthcare workers, that can work on the field. One of the areas that Sangath — an NGO co-founded by Patel — works in is training of individuals to deliver psychosocial interventions for a range of mental health conditions.

But where all the resources of the government currently stand, he believes the promise in the act, to provide free and fair treatment to all those below the poverty line “is ambiguous” and far from reality.

One way it could stand by its “duty bound” promise of providing care, treatment and rehabilitation, psychiatrist Dr Starlin Vijay Mythri says, would be by way of its inclusion of AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy).

The government instututions that do exist currently, still function in an asylum system, Starlin says, where there’s a lot of stigma attached. “There’s confinement of patients, with families not allowed for visits.” A councillor who has worked with a shelter home for mentally ill destitute women was in bad shape before her organisation stepped in.

“Patients were living in a pathetic condition, and the entire place smelt of urine”. While there were 40 staff members for the 100 patients admitted, they were clearly not looked after. They also found out that the lone visiting psychiatrist would prescribe the wrong medication.

So, while the Act is a much-needed change of law, on ground there’s a lot of work to be done by the authorities.