“Home means torture cell for us. Going back to Myanmar means wilfully walking into a lion’s den,” said Thomas, a Chin refugee living in Delhi for the last 12 years.

Inside the congested bylanes of a west Delhi locality, refugees from Myanmar’s Chin state are struggling to live with dignity since fleeing persecution at the hands of the state forces. In India, in search of refuge, they have found themselves in the throes of racist abuses and misery.

“If we return to Myanmar, we will be chopped into pieces. The state’s forces ensure that every part of our body is tortured before we are killed. And then our corpses are mutilated for the army’s entertainment. That is our situation,” said the 37-year-old.

Thomas, who runs a small grocery store for a living, is among the few thousands of Chin refugees living in West Delhi’s Hastsal village near Bodella.

Chins are an ethnic Christian community originally from Myanmar. They inhabit a mountain chain that roughly covers western Burma through to Mizoram in north-east India (where they are related to the Mizos, Kuki and others) and small parts of Bangladesh.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), India has registered between 3,000 and 4,000 Burmese living in Delhi, also primarily Chin, and estimates that over 600 Burmese are finding their way to Delhi each month.

“We are here because we fled to save our lives from the Tatmadaw (Burmese military) violence. We didn’t come here for fun. But, people in Delhi never fail to dehumanise us by calling us names and denying us apartments and our hard-earned wage,” said Lawman, a 31-year-old factory worker.

Lost fortunes

Samuel was a general physician at Matupi, one of the nine townships in Chin State, and was one of only three doctors in his entire locality. He belongs to a family of doctors who also happened to be the first responders at medical camps since 1990s when the military-led government began to aggressively persecute Chin Christians, cracking down on proselytisation, destroying places of worship, and attempting to forcefully convert believers to Buddhism.

Today, Samuel works at a medicine store as a compounder earning Rs 15,000 a month.

“I fled Burma (Myanmar) in 2020. When the world was battling pandemic, the Burmese were escaping butchery. My wife and I were working as doctors at one of the camps at the border adjoining India’s Mizoram, which is far more porous as Mizoram takes us in with open arms. We wanted to stay back and work for our people like my ancestors have done, until our neighbour’s house was burnt and their child was brutalised in front of us as a warning for all those who were working against the state’s forces,” said the 34-year-old.

Samuel, along with 11 of his family members, crossed over to India from Mizoram’s border that lies just 50 kilometres from the Chin state, in February 2020 and lived in the Northeast state for two years.

“Because of Mizoram’s proximity to Chin, India becomes our safest bet to ensure survival. We left everything behind, except for important documents and some money. But in Mizoram we couldn’t make much of a living as we were living in camps. We decided to come to Delhi with hopes of a better life,” he said.

The Mizoram state government and the NGOs have declared their determination to host the Chin refugees, calling them their ethnic kin and “brothers”, and have mobilised local support.

Here in Delhi, Samuel had initially spread the word about his medical proficiency, but “no one trusted” him.

“It’s as if a refugee loses all his knowledge, after losing his degree as soon as he crosses the border. I was forced to take up the job of a compounder because I have to run the household,” said Samuel, whose wife, a former doctor, is a homemaker now.

Samuel and his brother, who now works as a manager of attendance at a factory in Hastsal village, are the breadwinners of the family.

“Even though it is just around Rs 20,000 that we earn here, it’s not the lack of money that bothers us but the glaring disrespect,” he said.

Thirty-eight-year-old John and his family of eight lives in a 350 square feet house in Hastsal village.

“We were farmers back home and never had to worry about food. But look at us here! We don’t even have proper washrooms per family. We hardly earn around Rs 15,000 and depend on our community as a whole to survive,” said John.

Dire condition

John usually works at a glass factory in Hastsal during the day and spends the evening at Thomas’s grocery store to help him with online payment. “Most of us don’t even have bank accounts so this online payment is a huge problem for us. Plus, even though we can create a bank account with the help of a refugee card, the process is extremely tedious for us,” said John.

Majority of the refugees depend on ration distributed at the Don Bosco Refugee Assistance Programme at Bodella. The ration is sent by the UNHCR.

“We don’t even have money to buy food and basic groceries. Everything is spent on rent and electricity. Firstly, we don’t get flats easily as landlords blatantly tell us that they don’t want to invite ‘refugee problem’.

“Secondly, even if we get apartments, we are constantly threatened for money. Everyone knows about our hardships but no one wants to help us. In fact, we are thrown out of our flats when we fail to pay the rent or delay the payment by a week,” said Mike, who runs a small eatery.

“This eatery that I have opened is only to help my fellow people so there is no profit margin. How can I ask for money from my brothers? And locals are not so keen on eating here because there is so much stigma attached to us. We don’t get into arguments here because we fear consequences. Most of us are living here in Bodella because of its proximity to the Don Bosco Refugee centre,” he said.

The Chin refugees hope to leave India ‘at the earliest’. However, they are waiting for their exit visa from the Indian government.

“We fled absolute persecution in our home, but we don’t like it here because of how we are treated every day. But we are unable to even leave. The government does not give us exit visa so we are suffocating here,” he rued.

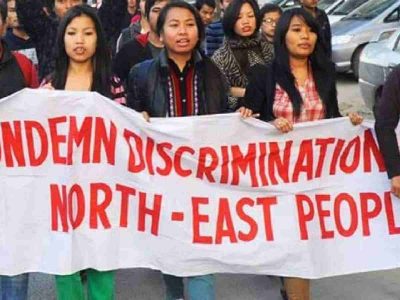

Racist slurs and intimidation

While India generally tolerates the presence of Burmese refugees, it does not afford them any legal protection, leaving them vulnerable to harassment, discrimination, and deportation as the country is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, nor does it have a domestic legal code to identify and protect refugees.

“We face disgusting racist jibes here. The moment we step out, people call us ‘aye Nepali’, all the time,” said Lamchin.

“We understand how people make fun of us. Even when we commute for daily needs, people hurl racist slurs like “Chinki” and “Chinaman” at us and we cannot even react because no one will hear us and we will face deportation, which means death for us,” he added.

For the women, beyond poverty and racism, there is a constant ‘sexual threat’ that restricts them within the four walls.

Laena Pi was working as a house-help at a local household near the Bodella market for over five years until 2019 when she had to quit her job due to ‘dangerous circumstances’.

“I used to work full-time at their (former employer) place till 2019. Initially, there was no disturbance and I was treated well by the lady and her children. Her husband, who worked in Agra, used to visit them every two weeks and that was never my headache until he shifted his work to Delhi around November, 2018. Two-three weeks into his stay, he began with his sexual innuendos and on many occasions cornered me in the kitchen. When I raised it with the landlady, she told me that my head is pre-occupied with such things, which is why I was making up stories. Meanwhile, the man never stopped with his lewd gestures. On January 19, when I requested her to intervene, he slapped me. That’s when I quit and let go off my salary of Rs 7,000,” she said, in broken Hindi.

“The problem is that no one comes to our rescue. The police make a mockery of us. Above all, it’s extremely difficult for us, especially women, because a handful of us working here struggle to communicate as we can barely speak Hindi or English,” she recalled her ordeal.

Most of the Chin women living in the area alleged similar incidents of sexual threat from locals.

“They target us for how we look. There is an absurd idea that we are sexually promiscuous and can be approached for sex. The (Chin) women here have to return to their homes before dark because we are harassed on the road, often molested. People openly say vulgar things like our women are available for multiple men because 10-12 people live together. We don’t live like that out of choice. It’s because we don’t get apartments and are forced to squeeze into one room sets,” said Sheon, translating for his wife Mani.