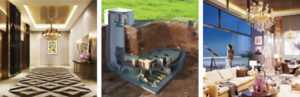

An apartment block under construction in Delhi is being marketed with a USP — it will have a nuclear bunker. Which provoked Patriot to find out what the rest of us can do to save ourselves in case of a nuclear war

Less than a kilometre from Shadipur Metro station, in a setting unlikely to produce any sense of grandeur with its rough, unpaved roads and billowing dust, lies the site where by May 2022 the ‘super luxury hotel residence’ called Raheja Navin Minar will be ready for occupation.

But pray, why should we care for apartments (which are under construction), even if they call themselves a “seven-star hotel branded & managed residence” or that it is in collaboration with Leela Hotels?

It’s a startling feature advertised alongside its swimming pools and ‘helipad restaurant’ — an underground nuclear bunker — which caught our attention.

We went to see where it all may happen. After a couple of questions by the man standing in military-esque fatigues behind the blue tin barricades, we were allowed in. With the delivery date of the project still almost two years away, there isn’t any building to see. The only standing structure along the path is an old bungalow into which we weren’t allowed.

Someone working with the developers told us that information on the nuclear bunker “was exclusive and shared only to the buyers”. Our efforts after that to contact the developers and the sales team yielded no results.

We just wanted to know: Why a nuclear bunker? What made them decide to build a structure which perhaps — and hopefully — would never be used and lie vacant with provisions like food, and water stocked up for its residents? Seems wasteful, a desperate attempt to stand out from the crowd. And perhaps a great selling point to a doomsday prepper which a YouTube search reveals would interest many Americans but no Indians.

The explanation might lie towards the border. This year, with conflict heating up between India and Pakistan and a lot of war rhetoric, a question does arise about the safety of the population if an attack were to happen.

The downhill trajectory in relations between the two neighbours began early this year when on February 14 a suicide attack on CRPF convoy at Pulwama left 40 personnel dead. India has accused Pakistan based Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) for the attack.

After that came the response by India called the ‘Balakot airstrikes’ where it went after the “terrorist training camps” by crossing the LoC. The relations between the countries never emerged out of the fiery cauldron and have gone further south after India announced in August 5 the revocation of special status of Jammu and Kashmir under article 370.

Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan warned not just India but the “whole world” of consequences if two nuclear-armed states have “direct military confrontation”. Basically, reminding everyone that both were armed to the teeth. A few days later though he said Pakistan would “never start the war” with India which was then called as being taken “out of context” by Pakistan foreign affairs ministry spokesperson Mohammad Faisal who tweeted that “there’s no change in Pakistan’s nuclear policy”.

India’s defence minister Rajnath Singh in his part said that the country’s long-held no first use nuclear weapons doctrine could change, “depending on circumstances”.

So, in all this war posturing which many news TV channels in India quite enjoy, the question remains: Would we survive to see the next day?

Some answers come from Prof. R Rajaraman, Emeritus Professor of Theoretical Physics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, who has written extensively on subjects of fissile material production in India and Pakistan, and the need for nuclear disarmament.

He puts it plainly, that there is “no prospect at all for saving the public from a nuclear attack”. Yes, there were anti-ballistic missiles which can stop the bomb from reaching but once it lands “there is not much one can do except for the political and military elite”.

There would be space, Prof Rajaraman says, “for a limited number of people and their command centres and the various electronics, and not for the public”, he adds that it’s “not because I know it in fact but because I know it would be impossible (to have everyone protected)”.

What he says isn’t just fluff. Much before we started thinking about such a situation, he along with Z Mian and AH Nayyar had written a paper called ‘Nuclear Civil Defence in South Asia: Is It Feasible?’. Published in Economic and Political Weekly in 2004, it points to the practicality of nuclear civil defence in south Asia.

It talks about how India and Pakistan “must seek to protect their citizens” from nuclear fallout while also pointing out the challenges that the two countries would face in order to do so.

In 2016, Sputnik — a Russian government owned news agency — had reported that Delhi Police planned “the creation of a control room that could secure data and communication against an attack using WMDs such as nuclear, chemical and biological” due to “perceived vulnerability of important communications and data networks in the case of airborne attacks in the capital city of India”.

In February this year, as things started heating up, it was reported that India is building more than 14,000 bunkers for families living along its border with Pakistan in J&K. This report had also quoted an official as saying that the bunker would be helpful only for ordinary shelling.

Prof Rajaraman thinks that even thinking about a way to save a larger number of the public would be “silly because it will not be possible. Nothing can be done.” He adds to this some very practical questions: How such a large area such as a city like Delhi would be able to be covered with bunkers, when one does not know where the bomb would hit. How many bunkers would be built for the entire population? How do you stock them with food?

When one looks at the property in Delhi and its promise, if the underground bunkers are built of the right depth and material, individuals inside would be protected from the blast. But how long would they stay inside, protected from the elements?

One must understand the nature of a nuclear blast. Prof Rajaraman explains that depending on the level of radiation, one may be able to get out from the bunker even within a day. “Most important thing is (to avoid) the original blast and the heat wave of the bomb. There will be some heavy radiation in the first few seconds but after that the problem is the fallout. If you are given normal protective suits you can come out (of the bunker).”

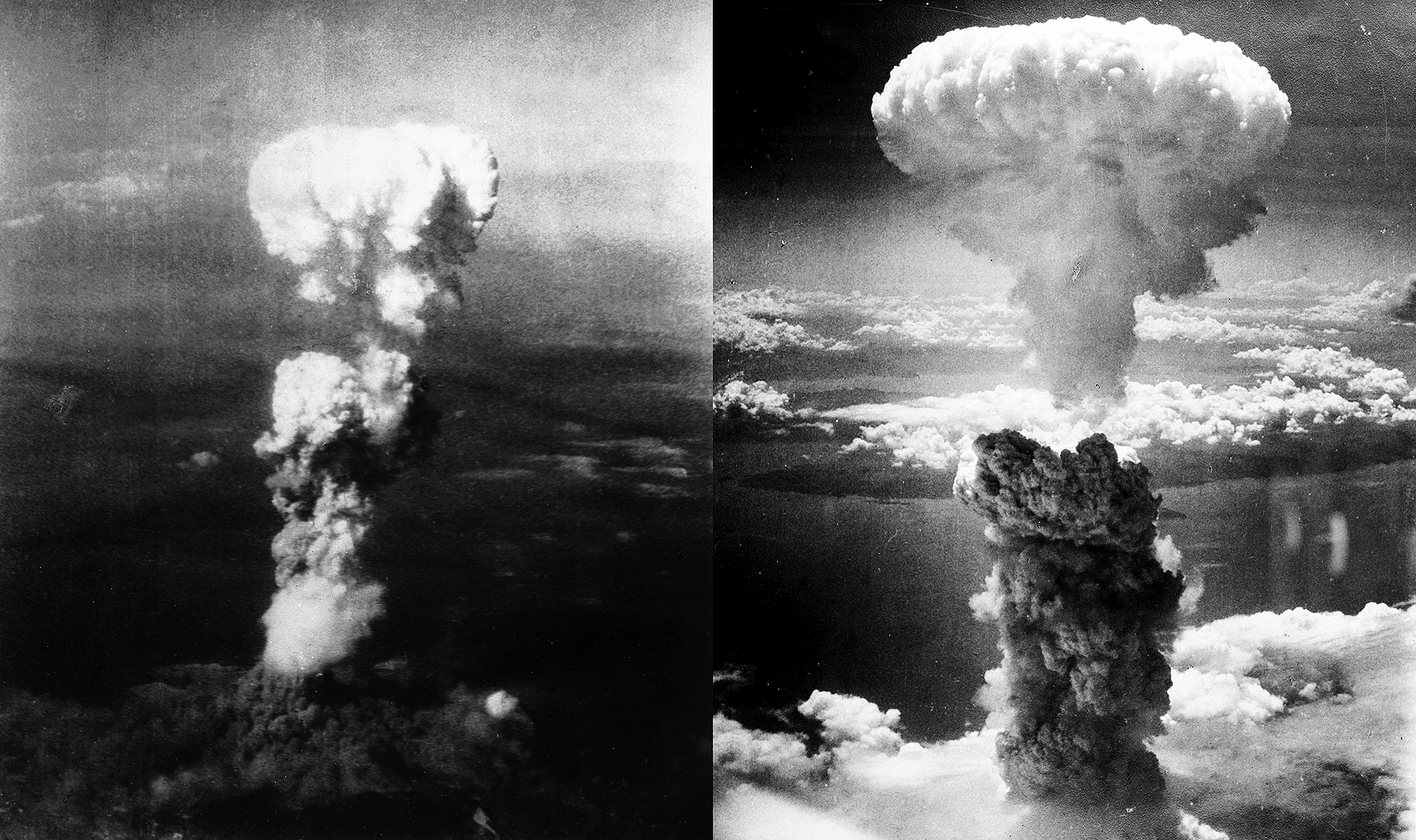

But this would happen only if it’s a low intensity blast. If it’s one like the atomic bombs used in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the disaster would be too far-reaching to have many survivors. The yield of the weapons made by India and Pakistan is “usually taken to be similar to those used” in the two attacks, i.e., in the 10-20 kiloton (kt) range.

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace had in a 2015 report said that Pakistan operates four plutonium production reactors; India operates one.

“Pakistan has the capability to produce perhaps 20 nuclear warheads annually; India appears to be producing about five warheads annually.” And the two countries together have at present more than 100 warheads each the size of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

If push comes to shove, one can only imagine what the scale of the disaster would be with just a few of these bombs dropped, let alone all.

Even when one bomb is dropped within the 10-20 kt, the inner zone around the nuclear explosion spreads out to distances of 1.5 km and would be more far-reaching, depending on the topography of Ground Zero, the wind and rainfall.

Even countries like the US and the UK which were pushing its people to build their own nuclear bunkers in the 60s “abandoned the idea”, says Prof Rajaraman “to save the public. Of course they didn’t say so in public”.

In Delhi, there’s at least one shelter all can run to: Delhi Metro’s underground stations. When they were being built, the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation were instructed “that the underground tunnel” must be “damage proof against any possible attack”.

But what happens after that —who will survive outside, what the fallout would be — cannot be known or fathomed. Prospects look grim for majority of the public. Thus avoiding war should be the first priority of our government rather than jingoistic warmongering. A bunker can only do so much, that too for a relatively small populace. What would be left for those who survive could just be an environment impossible to live in.