If a handset is stolen, the number will be blocked and be registered on a central black list. But the tradeoff is that your personal data could be easily leaked

When one speaks about privacy, one thinks about one’s home, one’s bedroom — and of course, goes without saying, one’s mobile.

One thing that follows us here, there and everywhere we go is our mobile phones. See parents on the Metro trying to divert their unruly and bored child using smartphone as a bait, or hundreds of people walking past with eyes glued on their phone or ears plugged with earphones. Mobile phones are ubiquitous even in villages where government’s initiative to build toilets have not reached.

The mobile’s reach is not always a boon. It has resulted in some very negative consequences like fake news spreading like wildfire and targeted attacks after rumours spread.

Now, there is a new development. The government will soon be registering all phones with International Mobile Equipment Identities (IMEI) numbers — a 12-digit number that each mobile handset carries — into the Central Equipment Identity Register (CEIR).

This registration of the number into a centralised database, the government says, will ensure that when a mobile is stolen, it will be marked on a black list when the Department of Telecom (DoT) is contacted. This means that the handset would be unable to access any cellular connection in the country, acting as a deterrent to the theft of these devices, as they would be of no use.

Currently, according to Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI), the number of active wireless subscribers in April 2019 is almost one billion — 999.68 million to be precise. This makes the registry a huge task.

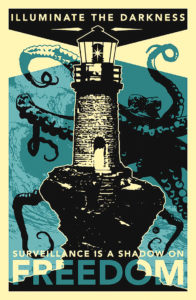

However, there is also the question of privacy: With all IMEI numbers in a central registry, could it open a floodgate of surveillance? Ritesh Bhatia, a cyber security expert and cyber crime investigator tells us that from a privacy perspective all our locations are easily detectable. Surveillance, he says “can be done anyway, so why would they need this?”.

Even so, he goes to say that a central registry would be open to misuse because “Data in different silos is safe, but once you bring them into one central bank, you’ll have to be extremely careful”.

Privacy has been the bone of contention with other security enhancers like CCTV cameras, which people believe more of would mean more chances of individuals being under surveillance. Even when the AAP-ruled Delhi government announced more CCTV cameras to ensure better safety of women, people brought up privacy.

The biggest fight in the question of privacy has to be about Aadhaar and its controversial requirement to receive benefits, to file income tax, amongst others. The most extreme comparison has been with Nazi Germany’s IBM records of all Jews which ensured people could be identified when the time came.

Gopal Krishna, lawyer and national convener of Citizens Forum for Civil Liberties, was one of the signatories in petitions challenging the government’s stand making Aadhaar mandatory. In an emailed response, he tells Patriot his views on the new registry.

Krishna uses harsher words than Bhatia when speaking about the implications of having such a central registry. He terms the ministry’s approach as “callous towards protection of absolute fundamental right to personal liberty and privacy”.

In a centralised database, Krishna says, the certainty that leakage would take place is given. “It is wise to keep sensitive data in diverse silos as decentralised data because convergence all the data is bound to have adverse implications for personal liberty and national security.”

He also draws the verdict of the Supreme Court on right to privacy and UID (Aadhaar) number, which “dealt with such aspect of meta data collection”. He refers to the Court underlining “how foreign intelligence agencies have been accessing metadata”, which was revealed “in the disclosures by Edward Snowden and WikiLeaks.”

CEIR, he says, when accessed and analysed, can lead to the creation of the “profile of an individual’s life, including medical conditions, political and religious viewpoints, associations, interactions and interests, much more than would be comprehensible from the content of communications.”

Even so, the difficulty in stopping this from happening lies in the fact that “legislative and judicial safeguards have afforded communications metadata a lower level of protection”, he points out.

If one looks at what exactly the initiative sets out to achieve and how it would do it — by blocking the IMEI digit — then here too, Krishna believes that the ministry has not factored in that these numbers can be chanced via an ‘IMEI cracker’ which can be procured through online forums.

Bhatia though believes that a majority of those who will steal the devices do not know how to crack the IMEI yet. He gives the example of the One-Time Password (OTP) requirement which was started on online transactions. “The crime went down. It took people long to come up with a different way to commit the crime”, he says.

He instead believes that such an initiative would keep vital data within one’s phone inaccessible, when stolen. “Somewhere on the phone, people store notes and passwords which are then used to access emails and bank accounts”.

What he points to being a problem instead is its execution. How the database will be constantly updated with new phones joining the fray every day, with almost a billion phones in the country already.

Krishna, though, fears the breach of database which would mean “breach in all aspects of personal and national life” at a time when citizens are facing “an unprecedented onslaught from the provisions for profiling and other related surveillance measures being bulldozed by unregulated and ungovernable technology.”

Unlike Bhatia, who thinks it is by and large a good initiative, Krishna is very sceptical when he says that “the proposal cannot be given any benefit of doubt” because the government “has failed to enact the privacy and data protection law”.