The girls of Mangolpuri don’t think twice before standing up to confront anti-social elements in their midst — or take refuge in safe houses when in dire straits

Mangolpuri is a region of north-west Delhi known to be steeped in crime, a reputation it established soon after those living in Turkman Gate were resettled there in 1976. Uprooted from a place where employment was easily accessible to the outskirts of the Capital, perhaps they had little chance to build a better life.

Now, its younger generation is fighting back – not the boys or men but the women. With a little help from the ‘Safer Cities’ initiative launched by the NGO, Plan India. What they did under this was pathbreaking, i.e making people accountable to their own communities.

Usha Devi, one such woman who decided to be part of this, believes that in two years, the lives of Mangolpuri’s women changed drastically. Devi, 50, is a mother of two girls. Her home is one of the 103 inducted in 2016 to give women in distress a safe place until the concerned authorities are alerted. “Whether it is day or night, I am there to help”, she says, adding that this year alone six cases have reached her doorstep.

Sapna, Devi’s 18-year-old daughter, is also happy. Since her home became a safe house, no one troubles them. Her confidence is visible when we make our way out from their one-room home with a bed, cooler and essentials lying around, to their shop (also a safe house). She bolts her door, no padlock, nothing, adding with a grin that no one would dare intrude. “They know we will not sit quietly,” she says with obvious satisfaction.

Devi tells us though, that being open to strangers any time of the day was not always easy. One night around 12 am, a girl started banging on the door. “Initially I was a little apprehensive as neighbours had warned that people will bang your door for help and then come and ransack your house. But when she started crying, I decided to open it.”

She discovered a girl who was being followed by two boys. She confronted them, called the police and saw that the boys were arrested.

It isn’t just cases of molestation, stalking and eve-teasing that come to safe houses. There have been family disputes, kidnapping, and child physical abuse which have come up in these last couple of years since the initiative started.

Why don’t the girls or families approach the police instead? “They don’t know if and how the police will help. They are generally scared that the police will not listen and just ignore them and their problems,” Devi answers.

What could be another factor, according to the young girls who are part of the ‘Girls champion of change’, is that there aren’t enough personnel patrolling the little lanes of their area anyway. And these safe houses are easily available for a woman when she’s in trouble.

Let’s look at the police presence. The police at Mangolpuri, which has a population of 7 lakh, have 14 beat teams for the entire region with one beat patrolling one block, some looking after two. Each beat has 4-5 personnel, with ranks ranging from Constable to Assistant Sub Inspector. While the mornings are mostly devoted to looking at schools and visiting senior citizens, their evening patrols are largely in parks. This is where a lot of boys, drug users and alcoholics hang around. There are also other spots vulnerable to teasing, snatching and such. But clearly, it’s not enough, as a constable at the Mangolpuri police station points out.

He says that while the sanctioned staff for the station is 150 personnel, their current strength is just 70. Out of this they have only four women constables and two investigative (women) officers, quite inadequate for the given population. And this is one of the factors to blame for the high crime rate in this outer district of the Capital city, because “if our visibility is there then crime will be less”.

The young girls, though, feel quite empowered now. “After ‘Safer Cities’ has come through, we have achieved a lot”, says Preity, a 12th class student who also plays touch rugby at the state level. “There used to be a lot of eve-teasing, but now we girls are aware that there is a law against it. We first understood what eve-teasing is and then after that we learnt that this shouldn’t happen and what should be done to stop it. We work with a lot of people to stop such things”, adds Anjali, an MA second year student.

“When we were in 9th, a lot of boys would stand outside and tease us”, Anjali admits. “Though no miracle has occurred to stop such activities, it’s in a lesser scale and we do feel much safer.”

Plan India’s partner here is AV Baliga Memorial Trust, which works at the grassroots. Jyoti Kandari, coordinator of the project with the Trust, says that with their extensive work in the area, they understood that girls had to first be made confident. “The police asked how would they know that one particular area was a hotbed for crime if no one complained?” Kandari says that this was a huge problem. “People didn’t file proper complaints. When and if someone did make a phone call, the police would reach but no one would be ready to speak out”.

“If eve teasing or harassment happens and one doesn’t complain then the boy will become a repeat offender and do this to someone else”, Kandari says, adding that the problem lay in the way girls were being raised. “Girls are sent out with the notion that they shouldn’t talk back, or react if they are teased, and if someone teases then you change your path but don’t fight back.” What is essential — as has been explained to these girls —is that they know their rights and have a voice that is heard.

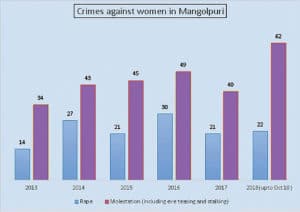

The official numbers for crimes against women vary from year to year. Some years they seem to be falling, but the next year get pulled back up again. But the police station has one thing to say about it — numbers cannot point to an increase in cases of crimes against women. Since the December 2012 gangrape case shook Delhi, Head Constable Amit Kumar says that people have become more aware and are reporting crimes.

The police themselves are “more active in the community”. This is through schemes such as Parivartan, “which teach self-defence and strive to impart stronger character traits in girls to be able to fight off unwanted people and to raise a voice,” Kumar says.

He believes people have been emboldened, which means more are coming out to complain. In 2015, 21 rape cases were reported in Mangolpuri, 30 in 2016, 21 again in 2017, and then 22 (till date) in 2018. Molestation cases (which includes stalking and eve-teasing) numbered 45 in 2015 and 49 in 2016. In 2017, molestation and stalking cases were 28 and eve- teasing at 12 while this year, until now, the cases of molestation and stalking are 50 and eve-teasing at 12.

On the ground, if you listen to the voices of the girls, and case workers of the NGOs, things are getting better. The reality, though, is that women are still being harassed or abused – of course, now there is help at hand.

Manish, who is now in BA second year, offers himself as an example of how perceptions can be changed, and how important it is to do so. He says that he used to think that girls “are nothing”. Recounting his not-so-proud past: “We would be a group of boys in school who would find girls to go behind, and pass comments”. He now proudly claims to defend girls and stops his friends from messing with them. “I tell them that girls are just like us and you must not treat them the way you do”.

Manish believes the problem lies with the feeling boys have that “they can do anything”. But, through proper education “this can change”. He is part of the team that goes and identifies problem areas. The team’s concerted efforts have ‘cleaned up’ areas like the Bhagat Singh Stadium which was a reservoir for “alcoholics and drug addicts”. It has been transformed into a place where they can exercise and play. They have also seen to the deployment of CCTV cameras on hot spots and street lighting in some.

Today’s Mangolpuri shows that if there were more safe houses, more training for boys and girls, and more police involvement in communities, Delhi as a whole will become a safer city. But only a collective effort can make a change.