The ongoing redevelopment in Sarojini Nagar has brought major changes in the lives of two families whose children spent their entire childhood in the area. Here they revisit the past and tell Patriot how much the area’s trees and plants matter to them

The vine from which he used to pluck grapes has disappeared. The lemon tree is dead now. Medicinal plants and herbs like fenugreek and coriander are nowhere in sight. It’s an abandoned locality, with plaster peeling off the walls, and almost no sign of human existence.

The Sarojini Nagar area is currently undergoing a complete makeover. The houses are empty, the lanes are bereft of human and vehicular movement. Once, there was life everywhere. It was inhabited by people from various cultures and backgrounds, united by their jobs with the central government. This was where they were allotted accommodation, and which became home for years.

Until one fine day, when they heard about the redevelopment. Households had to relocate or buy/rent their own homes. Not only was a way of life over, Sarojini Nagar’s entire ecosystem collapsed. Monkeys, birds and cats were deprived of their habitat.

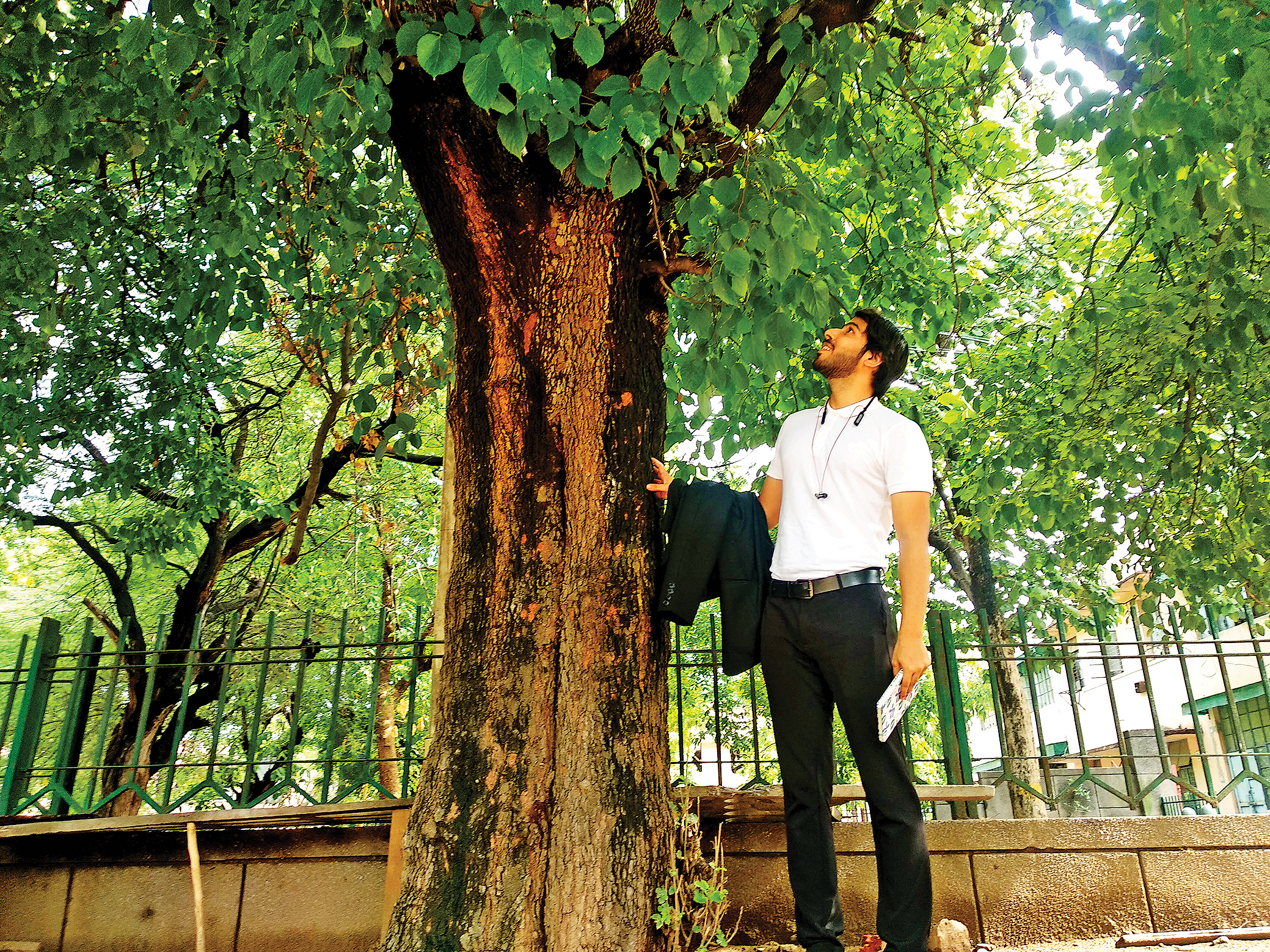

“You see those yellow flowers? During the monsoon, Amaltas was a riot of colour. I think they’ve trimmed the tree,” says a nostalgic Karan Tripathi, who spent his childhood growing up in Sarojini Nagar.

“When I was young, my sister used to think that the sky ends beyond that tree. Because we could not see anything beyond, it was double its current height,” he continues. “Imagine this tree which is completely dried up, used to be lush green, with crazy yellow flowers all over it. Look at it now.”

Like others in the neighbourhood, Tripathi was witness to the evolving flora in the area. When the residents left, the trees and plants also lost their former glory. The fact is that these trees and plants were being looked after by the residents, apart from being maintained by gardeners.

Tripathi recalls that one of their neighbours had marvellous gardening skills. Everyone in the colony simply called her ‘Daadi’. “All she wanted was to be around plants. She would help us with manure and seeding and tell us that we shouldn’t water a sapling until it’ three days old.” The lady herself nourished cherry and grape trees in her backyard, which today is overgrown with weeds and a sparse cover of grass.

Whiling through the neighbourhood, Tripathi reminisced about the trees he could identify from memory. He points out henna trees, which are rarely seen in the city. “There’s no way that a tree just dries up,” he says. “That’s definitely been cut up.”

Looking at a playground in front of his home, his eyes light up. “We used to camp here — get some stuff from our houses and put up tents, because it used to be so green. Now, there are only a few tufts of grass.”

Suddenly, he rushes up to the tree which he planted in his childhood. “My tree,” he calls it, “among the 15,000 trees here.” Next to it is a mulberry tree planted by his sister, from which they used to pluck shahtoot.

When the Tripathi family shifted to their new home in Kaushambi, his mother’s emotional connect with the plants was such that they hired another truck just for carrying the plants.

Recalling the days before the evacuation, he says, “Any empty patch you’d see, would have greenery. So much of it has been cut down.”

It was small consolation for him that so many people unanimously protested against the felling of the trees in Sarojini Nagar last year. Though the authorities modified their plans to allow some big trees to survive, it amounts to mere tokenism.

Going down memory lane, Tripathi says, “It was never an individualistic idea — no ‘my tree, my plant’. Neighbours would say, ‘Come and pick the fruits.’ I can tell so many stories about the guava tree in that block. Then with the mango tree in another block. It was not just a tree, a lot of narratives unfolded from generation to generations.”

He remembers the previous Mahashivratri, his mother couldn’t get home-grown jujubes. He reminded her: “In Sarojini Nagar, you just had to come out of the house and get them.”

While the Tripathis were able to take all their plants to their new home, another former resident Sneha Ganguly had to give away 200 out of 250 potted plants she had at the time because the verandah of her new home could not accommodate all the plants. Currently living in the swanky new multi-storey apartments in East Kidwai Nagar since March this year, she says, “These trees helped building a bond between neighbours, whom otherwise we wouldn’t know, because everyone’s so busy.”

“We had our terrace garden. We had our own coriander. In winters, we would have cabbage. Now the place to which we shifted is very boxy. We have been given two small and medium sized verandahs into which all the pots can’t fit,” she regrets.

Moreover, “We had seasonal vegetables in a kishti, which is slightly bigger than a pot. In these apartments, you can’t fit any of those.” So giving away almost 200 pots to relatives and friends was a task the Ganguly family had to perform reluctantly.

So how did they choose which ones to keep, and which to give away? “The tulsi plant is very important, we carried it with us. We kept jasmine plants too. The plants that were mostly decorative and some varieties of which we had more than one, we gave away,” says Ganguly.

They managed to transfer a champa tree with a lot of difficulty. But the plant that was used to flowering in an open space now no longer flowers, because of inadequate sunlight. This is true of other plants. “They’re surviving but not flowering. When you have to bring them to a smaller area you have to re-pot them, trim them down. So in a way you’re restricting their growth too,” she says.

Recalling the past, she says “The neighbours downstairs would call their backyards a safe haven. And it was so beautiful. In the evening, we would sit up on the terrace and we would hear the chirping of birds, not the sounds of construction. Her new building has no park, and it will take at least three years for the construction to be completed.

On the new set of people who would move in, she says, “A lot of people have many years left in service, and might be able to stay in the redeveloped Sarojini Nagar. But they won’t get the same kind of environment which we got while growing up.”

It’s not just the Ganguly family that feels sad about the complete change of lifestyle, but their gardener too, who has been with the family for over 18 years. He is not happy with the turn of events. He wonders, “What did the government do?”

Although she’s grateful to the government for the accommodation which it provides to its employees, she can’t help concluding, “It’s not living when you are in a matchbox 24×7.”