There is very little gender parity in the workplace when it comes to giving women fair compensation, in India. On top of that, there is wariness about the need for maternity leave arising

Ritika, currently an assistant HR manager in an MNC in Delhi, was shocked when a consultancy firm recruiting for a manufacturing company called and asked her all sorts of personal questions. The role of the HR business partner was apparently “a very important position” the caller said repeatedly, and that they couldn’t take a chance with someone who was going to get pregnant anytime soon. “I was so shocked at that point”, Ritika (name changed) says, that she told him she wasn’t planning on having children any time in the near future. He then went on to ask if she had had the discussion with her husband before making such a decision. Before this, he had already asked her age and marital status and obviously deemed her fit and ready to have a baby.

Ritika adds that many a time, potential employees will also ask about how comfortable they are with late working hours, “I don’t know where this comes from,” she adds, “would they also ask this to men?” I think not.

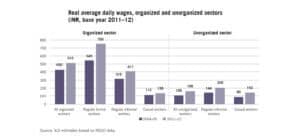

International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) 2018 wage report says that the wage gap has narrowed in India, but it also points to the very important fact that it still exists — and in big numbers. But it’s not just that women are paid less even though they share the same skills set, education and work experience as men, but they are also highly under represented.

In a response to emailed queries, ILOs wage specialist Xavier Estupinan points out that in urban areas of India, while the gender wage gap in public administration is at 38% for lowest job categories, it reduces to 14% as one went up the ladder. He adds, that the important factor to keep in mind, when reading this should be that “although the wage gap shrinks at senior level positions, the women participation rate also declines substantially.”

In sectors, such as manufacturing, the gender wage gap is as high as 43% for elementary occupations and as low as 11% for higher level positions like senior officials and managers. And while in the education sector, we find higher women participation, the gender wage gap continues to be high at the lower occupational levels i.e. around 51% and shrinks to 16% at senior official levels. Further, the issue is that wages at senior level in the education sector correspond to 56% of the value of wages women receive at a similar position in the manufacturing sector.

But to again get things in perspective, even with a decline in gender wage gap at top levels, out of all regular employment in all sectors in India, Estupinan says, the overall women’s share of participation in senior levels hardly reaches 1%!

Why is that many women hardly make it to the top? It could be down to the fact that they have to leave the job market to support families as most still believe in the responsibility of a household solely depending on a woman. ILOs 2018 report ‘Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work’ reveals that women in India, on an average, spend 297 minutes per day on unpaid care work while men spent just 31 minutes.

This thus becomes an important factor why women can’t join the regular workforce when they have so many other responsibilities. In the wage gap, another eye-opening fact is that the age of women and the number of children at home are direct factors for influencing the wage difference. Estupinan adds that as we move up the age cohorts, the gender wage gap increases.

He says, however, that one can’t just point and say that men are preferred over women in the country. The complexity of the Indian labour market is that it carries “still many hurdles”. He adds that women end up working greater share of their time in part-time jobs, yet they draw a lower pay than those who are employed in full-time jobs.

WageIndicator.com found that women below the age of 30 earned 23.07% less than men, while those in the age group of 30-40 years earned 30.24% less than men. Surprisingly, educational qualifications also end up increasing this wage gap.

According to World Bank, in 2014, the total participation of women in the labour force was pegged at only 24.2%. Even though the figures were expected to increase, the astonishing reality is that there has been a 23% decline in the female labour force participation in our country over the last 25 years. With women constituting almost half of the population (48%), these numbers should be a wake-up call for the country.

A paper prepared for the 5th Conference of the Regulating for Decent Work Network last year titled ‘Indian Labour Market and Position of Women: Gender Pay Gap in the Indian Formal Sector’ points to women being undervalued. With a prevalent patriarchal mindset that still believes that a woman is only okay for a more caregiving job than those which require them to be decision-makers or even taskmasters.

The paper also points to the fact that many a time, a top job is not given to a woman, because men don’t like taking orders from them. There can also be “unfavourable social interactions on the job” which can lead to, it says decreased efficiency at work. But one should add that workplace can also be a scenario where women will be vulnerable to sexual, and mental abuse.

This means companies not only have to make a completely unbiased approach to women and men at the workplace but also safeguard women’s safety.

Then there’s the maternity break. When they decide to step down from the regular labour market and come back after a break, they are often offered lower wages compared to their male colleagues, says the paper.

As the beginning of this report tells us, women are often judged for their reproductive age or marital status. What must the government then do? Its Maternity Act of 2017 was lauded, which gave mothers the entitlement of receiving six months leave. But what again shows the disenfranchised nature of care is that there is no law for paternity leave. This reinforces the belief that women are the sole carers for children. Aya Matsuura, gender specialist at ILO tells Patriot that addressing the fact that care work is currently borne mostly by women, is important to be able to foster gender equality in the world of work in India.

She also adds that while paid leave for the mother is a progressive move, the next step should be towards extending maternity coverage to all working mothers.

Women at the end of the day are judged and picked through the long unending queue of potential employees, not just for being mothers, but also for being the age which would mean they are looked at as potential mothers. Then there are the unmarried women, who are again often refused jobs because the potential for them to quit once they get married and relocate with their spouse stands.

And when they do get a job, they are not paid at par with their male counterparts.