Why lightning strikes are a bigger fear than Covid in Bihar

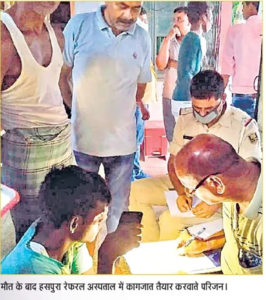

Under the glow of a mobile phone, a relative gathers paperwork for the dead at the Haspura Referral Hospital in south Bihar’s Aurangabad district. That’s how Hindustan, the state’s most-read daily, captured the tragedy of the recent deaths in a lightning strike, through a photograph.

As Hindustan reported, Vipin Kumar, 18, was grazing his three buffaloes in Nanhu Bigha village in Aurangabad when the heavy rains began. As he rushed his buffaloes back home, lightning struck, leaving the buffaloes dead while Vipin himself was declared dead at the hospital in Haspura. In the same police station jurisdiction, Sapna, 8, of Taal village and Arjun Kumar, 14, of Sihari also died from the lightning strike.

Vipin, Sapna and Arjun were among the 83 killed on June 25, in 24 hours of rains and thunderstorms in the state. With around 30 injured, this death roll has been confirmed by the state disaster management authority, though some regional dailies like Prabhat Khabar placed the number of deaths as high as 103.

The official break-up of fatalities showed that 23 out of Bihar’s 38 districts recorded deaths by lightning strikes. Gopalganj had the highest fatalities with 13 deaths, followed by Madhubani and Nawada (eight each); Siwan and Bhagalpur (six each); East Champaran, Darbhanga and Banka (five each); Khagaria and Aurangabad (three each); West Champaran, Kishanganj, Jehanabad, Jamui, Purnea, Supaul, Buxar and Kaimur (two each); and Samastipur, Sheohar, Saran, Sitamarhi and Madhepura with one death each.

Even though the single-day toll of 83 is the highest for the season, 196 lives have already been lost in the last four months to lightning strikes and thunderstorms in Bihar. On April 19, for instance, five people died, according to the state disaster management body. Six died on April 22, and 12 on April 26. On May 1, seven people were killed in a lightning strike, 12 on May 6, two on May 7, and five on May 19.

Moreover, this year is not an exception. Over the last 10 years, lightning strikes and thunderstorms have claimed 2,480 lives in Bihar — an average of 248 deaths per year. According to Prabhat Khabar, there were 221 lightning-related deaths last year, while the number of casualties was as high as 514 in 2017.

While expressing grief over the loss of lives, the chief minister’s office announced compensation of Rs 4 lakh each to the families of the dead, and arranged treatment for the injured. The Patna Meteorological Centre has predicted more rains and thunderstorms over the next 72 hours. Meanwhile, the state disaster management body has released a list of precautionary measures for people facing weather conditions that accompany thanka, as the locals call lightning. An advisory has also been placed in newspapers published from Bihar.

The disaster management body has also developed a mobile app, Indravajra, to warn people about the possibility of lightning-like weather conditions, and has urged people to download it.

Even by the cold logic of numbers, the horror of the deaths and injuries caused by the lightning strikes has gripped citizens far more than the Covid-19 pandemic. Coronavirus has claimed only 56 lives in Bihar so far, with a recovery rate of 77 percent — the third-highest in the country. With 8,488 positive cases, the government has said that 1,81,737 samples were tested, including a high percentage of testing of migrants returning to the state.

The death rate has been well below even one percent of positive cases. If there was no sign of panic in Bihar over the pandemic, the numbers haven’t brought any anxiety either.

On the other hand, the fatalities caused by lightning strikes included people working in the fields: engaged in the active paddy-growing season, or grazing cattle. Besides, at least 26 children died. In Banka district, for instance, three children, Vasudev, Raghunandan and Shashikant, were killed. The loss of cattle — a vital economic resource for farming families — has also been high, particularly in Khagaria, Bhagalpur, Darbhanga, Nawada and Madhubani districts.

The lightning deaths seems to be a deadly prelude to another annual disaster in the offing. With the onset of the monsoon, flood-prone regions around the Koshi and Gandak rivers sense the ominous advance of watery ravages. But unlike floods, the lightning disaster cannot be milked for political blame-games. As in the case of earthquakes, incriminations are out of the question over the preventive role of the government in power. However, relief measures will still be subjected to political scrutiny — more so in a state which is only a few months away from the Assembly poll.

In disaster-hardened Bihar, the idiomatic bolt from the blue now has a deadly regularity that beats its meaning. In its annual scale, the deadly silence that thunderstorms and lightning strikes inflict across the country needs more attention and coverage to improve response patterns, if not for anything else.

It has been documented that lightning is a deadlier killer in India than other extreme weather events, perhaps even the deadliest. More stories must be told on what preceded that sudden snap of death, and told to more people to see how they can escape it.

www.newslaundry.com

(Cover: The photograph in Hindustan)