Signboards on every lamp post ban people from parking. Yet these top lawyers claim they are not flouting rules, some blame their drivers, some just say they are innocent. But Patriot witnessed and photographed the illegal activity

From an auto rickshaw driver to a parking attendant, a traffic police constable to a senior advocate, one common belief is that lawyers don’t care to abide by the law — while their professional commitment is to uphold it for their clients and ensure justice.

And leading by example are the likes of former Delhi High Court Bar Council chairman, former Kerala High Court Chief Justice and other senior advocates.

The High Court’s order strictly prohibiting vehicles from being parked on the periphery of the Court on Sher Shah Road came into place in November 2017. It said, “regardless of their owners (litigants, officials or lawyers)”, everyone has to park their cars in the underground parking facility in the court premises.

A visit to the court by the Patriot team found the reality to be totally different.

At the five-storey underground parking facility, opened in 2014, a maximum of 1,000 cars are present on a daily basis. This is half of the holding capacity. So where are all the others cars parked? Parking attendant Ravinder knows the answer. He points out, “Lawyers don’t have the time to wait and watch their car being parked. They are in a rush”.

It takes about 5-7 minutes to park the car using one of the 20 lifts at the site. The person drops their car off, the attendants put in the car number and off it goes to one of the free levels.

The system is in place. But instead of taking advantage of it, they park out on the street, where big signboards scream “By order of the High Court, no parking, no waiting, tow away zone” and “Vehicles parked on the road will be clamped” at almost every lamp post.

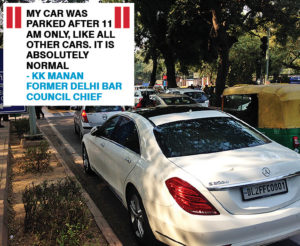

Who is defying these orders? Former Delhi Bar Council chairman and senior advocate KK Manan had his white Mercedes parked outside Gate No. 5 both on Monday, December 3 and Tuesday December 4, for more than three hours while we waited and watched. When contacted, he said, “The cars are allowed to park outside the high court only after 11 am. My car was parked after 11 am only, like all other cars. It is absolutely normal.”

Nowhere in sight is there a sign allowing such a leeway. And Gate No. 5, he must know, is where a major blast took place only seven years ago.

Manan adds, “Cars with chauffeurs are allowed to park on the road, hence I park there.” However, in the notice by the Court it is clearly stipulated that vehicles, especially those driven by chauffeurs have to be parked inside the underground car parking facility.

In fact, we found that during the period between 11 am to 3 pm, a slew of cars came and stopped near the gate. Lawyers got down, took their time to put on their signature black coats, while the car blocked the road, bringing traffic to a halt.

Those that were leaving had their drivers waiting as they gingerly removed the layer of black, put their files in and lowered themselves into the car while the driver put the coat in a hanger.

During peak hour, this dressing and undressing is not just aggravating for those on the road but also seriously challenging for the traffic situation.

Rakesh Tiku, also a former Delhi Bar Council chief, says that with the peak hour being “from 9:30 am to 12:30 pm”, violations such as this cause congestion and a potentially dangerous situation.

It’s not as if the area around the court is a safe zone. Tiku, who was the chief when the Delhi High Court blasts of May and September 2011 took place, blames security lapses. In the first one, there were no casualties. The latter, which took place at the reception area of Gate No. 5, left 15 dead and many more injured.

Lessons should have been learnt from this incident. But around this very same gate, cars block the street during peak hours — a safety and traffic hazard. This includes cars with Government of India number plates and those of the Delhi Government.

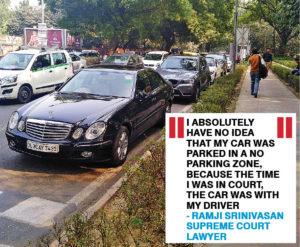

Among them is the black Mercedes of senior advocate of the Supreme Court and chairman of Assocham’s competition committee, Ramji Srinivasan. It was parked outside Gate No. 5 for more than three hours.

The car dropped him off around 12 noon near the gate, and left with him around 3 pm on Tuesday, December 3. “I absolutely have no idea that my car was parked in a No Parking zone, because the time I was in court, the car was with my driver” he said, when contacted.

Another senior advocate Akhil Sibal, son of former Union Minister Kapil Sibal said, “My car drops me off, and when I come out of court, it picks me up again from the gate. So, I have nothing to comment regarding whether my car was parked in a No Parking zone”. His blue BMW X3 was parked outside Gate No. 5 for more than two hours.

A black Toyota Innova belonging to former Kerala chief justice VK Bali also stood in the same area outside Gate No. 5. “I assure you that my car was not parked there for more than 3-4 minutes”, said Bali when contacted.

He went on to say that his assistant rings the driver up “once I’m done with the court proceedings, then the driver comes to the gate to pick me up. It is only then that my car is in the area in front of the court, otherwise it is parked in the designated parking space”. Contrary to his defence, his car was in fact parked close to Gate No. 5, from 12 pm to 4 pm.

Senior advocate Hiren Dasan, whose white Innova was parked for more than an hour outside the High Court, says that he isn’t at all aware of where his car remains parked. “It must have been my driver’s fault, and I will speak to him regarding this matter” Dasan promised Patriot.The order also mentions that the Delhi High Court Bar Association should ensure that cars are not parked on the road. When contacted, its President Navin Uppal refused to comment, adding that he had no idea about the situation.

Near Gate No. 5, there is a notice issued by the High Court, dated November 26, 2018, which clearly states that all must park their cars at the underground parking facility on Sher Shah Road, and for those who do not comply, their cars will be clamped and towed away.

The traffic constable posted in the area says when visitors and their drivers are asked to move they generally abide, but “it’s the lawyers and their drivers who don’t”. “We warn the lawyers every day, but they don’t pay any heed to our warnings at all”, he added.

He said 100 challans are sometimes cut at the area worth Rs 600 each a day on an average. But it does not work as a deterrent, as “these lawyers are rich, and Rs 600 is not a big deal for them”.

For him, no day goes by without warning people, asking them to move and issuing these challans. With only two clamps, there’s nothing more he can do.

An auto driver in front of the High Court says that he, along with many other drivers linger there waiting for customers until a traffic policeman chases them away. “But it is only us that they target. These lawyers get away with everything. No one tells them anything”, he adds.

ACP, Traffic, Central District, Ramphal Bhura says that they “make as much effort to keep violations in check”, with “maximum challan that we can do”.

Explaining the psychology, another senior officer in the traffic police said that despite multi-level parking, people would rather park on the street than spend five extra minutes to park their vehicle. Exactly what the parking attendant said.

Advocate Tiku, agreeing with our findings, added that many lawyers preferred to park outside on the road, “despite being issued directions to park in the parking area, time and again”.

Furthermore, he cited that at Gate Nos. 7, 8 and 9, lawyers with Delhi HC stickers are provided with free parking space – “an area which can accommodate about 800-900 cars”.

Where lies the problem? “Hindustani mentality”, which is all about the “shortcut” he says.

He is not so concerned about the security situation. With frisking and bag checking taking place before anyone enters, he says the “situation is much better than earlier”.

The traffic violations, though, are a glaring truth about how the lawyers themselves do not abide by the law which enables them to earn their Mercedes and BMWs. The Delhi High Court, which passed these orders, has to look away when such violations take place right under their noses.

After the blast at Gate No. 5…

At 10:14 am, September 7, 2011, the lives of 79 people changed and 15 stopped – some that very moment and some in the following days and months.

Among the 79 were Imran and Rashid Ali, cousin brothers who with Ali’s father and elder brother had come to the Court from Khureji close to the Ghaziabad border for the first hearing of a case filed by their sister against them.

The blast left Ali’s right arm almost immobile. The little strength he has to just clench his fist returned after almost two years of therapy. Imran lost hearing in his left ear. Rashid’s father is also hard of hearing, and his elder brother has now recovered after numerous surgeries for his leg injury.

To this day, Imran and Rashid fear crowds. “I think something may happen again. So, I get out of there and stay at home”. Imran was just 27 years old when the blast took place. Now, his dreams show reruns of those traumatic minutes: people with their arms and legs torn off, some their heads. “I can’t speak to anyone about it. Who will listen?” he asks.

Imran, who works at a garage in Vaishali, thinks his brother’s life has been affected more. Rashid was then just 24 years old. “I stay at home most of the time,” he says. “Earlier, my life was good, Imran and I used to work in my father’s shop in Karol Bagh. Now only my father looks after the shop.” Rashid does not go there anymore.

They had also been promised help to secure jobs, “We didn’t get it, nor has anyone come to us again to ask about our welfare. I can’t live the same way I used to earlier. Slowly I have recovered from the mental impact that this blast had on me. Even when a tyre bursts, I get so scared. I still have so much fear in me”, a visibly affected Rashid tells us.

It took him a month to be able to speak to his family again and another to go back home in November that year.

Imran says they didn’t believe Rashid would make it. “We thought he was gone. But he recovered after a long struggle”.

The aftermath

“It was around 10:10 am when we were at the reception area to get the pass made. We got it done and while moving on to sign in a register the blast happened”.

Thinking about that fateful day, they dwell on the security lapses and point out that officials couldn’t see a lone briefcase just lying there. They hope everyone has become more vigilant.

But the traffic nuisance, they say, is still evident. “Cars are still parked outside, and a crowd congregates. Big lawyers with their big BMWs and Mercedes park their cars there because they don’t care about the law.”

After the blast, Rashid lost consciousness. Imran took him to the hospital in a police jeep, where treatment was good. But after a month or two when they returned, the questioning begun.

“NIA (National Investigation Agency) were after us saying you all are Muslim — as we were four members of the same (Muslim) family. They started questioning us, what happened, how did it happen?”

Rashid believes that if they weren’t injured, they would have instantly been put into prison. But the harassment continued. “People from different security agencies would come home, or call us for questioning. It happened at least 10 times.”

For their injuries, the two brothers received compensation of Rs 2 lakh each. Rashid’s father and elder brother got Rs 20,000. They later went to Court, with Imran getting Rs 7 lakh more in 2015, after four years of the blast, and Rashid getting his in 2017.

“My lawyer Gaurav Bansal worked really hard. The government did not want to give us more cash because in earlier blast cases the compensation had been this amount,” Imran says. His lawyer argued that they had come to the court that day to get justice.

Bansal argued that those who are living keep suffering. “They also thought that the families who lost their loved ones should be compensated with Rs 10 lakh and not those who survived.”

Both Imran and Rashid have disability certificates, receiving Rs 2,500 in disability pension, clearly not enough when you pay rent of Rs 5,000, as Imran does. So, he works “extra hard”.

He also went to court for his children’s education. “After the blast the government said they would look after it, but it never happened.” A newspaper then declared they had won the case, but “I went to fill a form and they denied admission.”

While they say that the government didn’t keep its promises, they don’t have the energy to fight anymore. With more than half their lives in front of them, they have adopted a more pragmatic approach towards their situation.