BR Ambedkar’s exhortation to Dalits – Educate, Agitate, Organise – is given context and meaning in this anthology of poetry and stories

Growing up, I had seen the world through a casteist lens. To be more specific, I viewed classmates who got admission through reservation as ‘lesser students’ because being upper caste, I was building my beliefs on a hollow notion of merit.

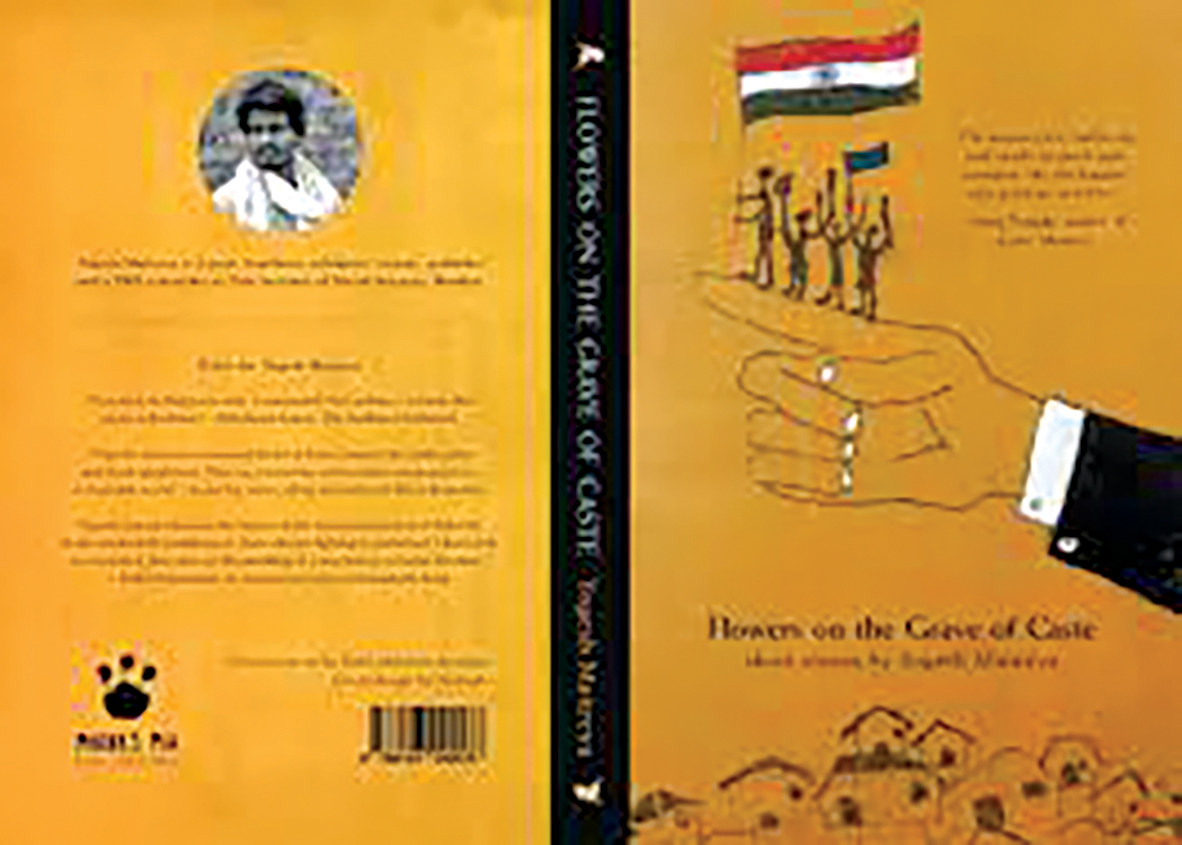

Yogesh Maitreya’s collection of poetry as well as stories introduced me to a whole new world of Dalit literature. The way he uses Ambedkarite principles and describes atrocities on lower caste people has completely changed the lens through which I view the world. In his recent book Flowers on the Grave of Caste, Yogesh has drawn parallels to ground realities in educational institutions as well as society – realities that we as upper caste people are never exposed to it.

In the first story ‘Re-Evolution’, Yogesh has thrown light on how a young boy Milind instead of taking up a job goes back to his roots to educate children (message of Dr BR Ambedkar) and is killed by a local landlord due to caste hatred. The protagonist Baliraja has to go through torture at the hands of the state machinery not because he had committed some crime but because he belonged to a lower caste. Upper caste Patils always suspect him of every theft that takes place in the village. Baliraja’s wife Mariaai is subjected to rape by the Patils and burnt alive in the hut.

The story throws light on Babasaheb’s emphasis on education, as Baliraja wants his son Eklavya to pursue his dreams and study — unlike the traditional Eklavya who gave away his thumb. Readers are left pondering upon the life of a lower caste individual in the scenario when even the state machinery works according to the dominant upper caste.

In the story ‘Caste’, Yogesh has brought into focus how people are reduced to mere subjects of research and about the character of pseudo-Marxists who are not comfortable even eating in the company of lower caste people. A character of the story Gargi asks, “How do people live here?” to which the protagonist replies, “Not by choice, obviously. In your comfort lies the history of their discomfort.” The writer has subtly pointed out the hypocrisy of the Left-wing movement which talks about socialism but in reality is reluctant to uplift the lower caste which in their terms is the “labour class”.

In ‘The Sense of the Beginning’, the protagonist of the story Kabir falls in love with a girl of a different religion, Saira. Their love gets no recognition outside the academic space they are residing in. Kabir’s rejection puts him through a difficult existential crisis phase where he turns to smoking weed. Kabir’s hostel-mate Siddhartha also goes through the trauma of being mocked by the administration of the elite institute for his lack of fluency in English. Eventually, Siddharth takes his own life.

In ‘Life is Beautiful,’ the author has thrown light on how the Brahmins get reservation in every white- collar job in India whereas a lower caste person has to drop out of education because of lack of funds and resources. The protagonist Vishnu falls and dies in the same manhole which Nagraj was repairing. The author shows how people cannot even dream of education because of the vacuum created by the monster called caste and are forced to take up jobs traditionally prescribed for them by the regressive Manusmriti.

In ‘Flowers on the Grave of Caste,’ the author has painted a picture of caste being a notion created by humans after birth. When a person dies, he has no caste or religion.

‘Educate, Agitate and Organise’ is the longest story in this anthology. The author shows how even the city of dreams Mumbai fails to fulfill the dreams of a lower caste person when he is unable to get justice by the legal machinery. The protagonist somehow reaches Delhi, where in the academic campus he is made aware of the corrupt minds in educational institutes. The author also introduces a strong character of Ashoka, who comprehends Babasaheb’s life message: Educate, Agitate, Organise.

This book is a must-read for everyone and an eye-opener for upper caste people who always bring the notion of merit in discussions. Here Ambedkarite principles are beautifully potrayed through simple stories in English, a language of elite and upper caste people. The author has shown how it feels to be born in a marginalised section of the society and the atrocities committed on them. The stories send a chill down the spine, giving readers a clear picture of how caste works in different contexts of Indian society.