Good journalism needs to dissect bad science

Do you want to burn those pesky belly fat? According to NDTV, fruits, tulsi tea, juices, nuts, homemade drinks, laughing, NDTV special belly-shrinking citrusy tea, seeds, hung curd, ghee, vegetables, quinoa, cumin, carbon dioxide, chicken soup, milk, raw garlic, egg and frankly almost anything left in your kitchen will help. These are just some of the articles published by NDTV in the last couple of months that have the word “belly” in their title. A short teaser for NDTV’s inventory of 400+ articles on vanquishing the stubborn belly fat.

If you are beginning to think NDTV must be the industry leader in this absurdity, you are mistaken. In this very competitive spot, portals like Times Now and The Times of India have their own niche. Superfoods, fad diets, natural detox, organic goodness, magic juice/tea, weight pills, etc., are routinely packaged with clickbait titles and spewed across the Internet. These articles are often based on poor or no scientific evidence.

The modus operandi is simple. Take some relatively healthy food, add some token terms like antioxidants, good fats, high metabolism, lean fibre and voila! You have made a clickbait cash cow. Not only are these articles woefully misleading, but are often home to ridiculous ideas that have not been vetted by good science.

Good and Bad Science

If you look at these articles carefully, you’ll find a recurring theme. They will take a colloquially healthy food item like veggies or fruits and oversell its inherent nutritive value with flowery phrases like superfood and claims that have little basis in science. This overestimation of research in part stems from the inherent flaws in nutritional epidemiology.

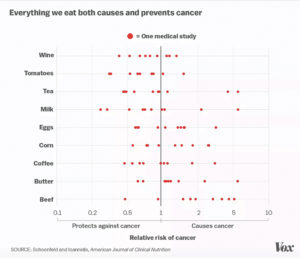

Let me illustrate this with an example. You would have often seen headlines that say “research shows that food X increase/decreases cancer risk”. This “X” is sometimes coffee, sometimes wine and sometimes some food you really like. Turns out, you can replace “X” with almost any food. In this interesting 2013 paper, prolific researcher John Ioannidis found that 40 of the 50 most common ingredients used in cooking have scientific studies that associate them with some form of cancer risk. Most of these studies are too small, not reproducible, biased or methodologically flawed for the conclusion they draw.

The lack of reproducibility and the inherently complex nature of nutrition makes it difficult to conduct robust research. This 2018 review by John Ioannidis is a good primer on the subject. This lack of rigorous and meticulous research is used by news portals to churn articles with eyeball-grabbing headlines that are far from the truth.

It is good journalism’s responsibility to tackle such bad science. Consider this front page Times of India article that claims that skipping breakfast increases the risk of heart attacks by 35% which, according to the same article, is more than obesity (33%). The research paper that TOI cites assumes causality and does not address flaws like confounding variables. Good journalism questions this before printing outlandish claims like this which would petrify any reasonable cardiologist. This 2016 New York Times piece on skipping breakfast is an excellent example of how good journalism dissects bad science.

Good Journalism and Bad Journalism

There have been many instances of articles with freakish claims citing a paper published in predatory journals. Rigorous peer review is the hallmark of good science. It is essentially a group of unrelated experts who vet your research claims thoroughly before it gets published as a scientific paper. Predatory journals happily skip this phase and publish any bizarre paper for a high fee. Most reporters don’t appraise the credibility of such papers and happily publish a piece on them for some cheap clicks.

Good journalism critically reads the entire research paper they and not just the accompanying PR release. They also don’t recycle misleading content from habitual international offenders like The Daily Mail. Editors should also screen the paper for conditions like adequate sample size, funding, randomisation, blinding, conflict of interest and highlight the shortcomings if they decide to print it anyway.

Providing a platform to these unchecked claims robs the readers of genuine advancement in science. All these articles on belly fat no longer seem comical when you take a look at India’s obesity epidemic. Studies show that more than half of the folks in urban settings like Delhi are obese. As the precursor to cardiovascular ailments, type two diabetes, several types of cancers, obesity is a nightmare for an already paralysed healthcare system. The average reader of NDTV or Times of India is concerned about their belly. This perturbation of obesity is the bait that the above examples rely on. Why would you not trust the belly shrinking citrus tea if the otherwise credible NDTV is saying so? For something that is so dangerously prevalent, bad journalism should not be the most accessible source of remedies.

The clickbait model This issue becomes more intelligible when you dive deeper into the economics of the clickbait model. When your income is reliant on traffic, you’ll do anything to increase it. Even if it means disguising lifestyle pieces as health journalism. Most news houses survive on clicks. It doesn’t matter how, more the clicks your piece gets, more the money you mint. A detailed well-researched piece is no good on the balance sheet if it can’t get the readers to see the damn ads.

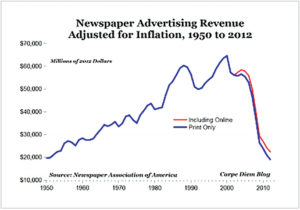

Frankly, news can no longer survive on advertisement which was, for now, its only source of sustenance. The advent of the internet was the death knell of print media. The graph below is an alibi of this downfall.

The shift from print to digital is equally bad as large companies like Google, Facebook and Amazon swallows 60% of the ad revenue. This has made digital advertisements a wasteland akin to the one in Mad Max. Hundreds of different news portals have sprouted up, all of which are fighting with preposterous clickbait headlines to get our attention.

The current model that relies on ad money perpetuates bad science. Unlike the subscription or the donation model, where the incentive is on good articles that increase subscription, the clickbait model relies on you clicking the article, not necessarily liking it.

As most news portals shift their strategy to digital-first, this neighbourhood gossip in the name of health reporting will increase substantially. Along with the spread of misinformation, loss of credibility is one of many consequences of bad science. If your reporters are busy writing about the next fad diet, who will cover important health issues like drug pricing and universal coverage? Corporate pockets are the only ones that benefit from this model of chasing clicks.

If the advertisements sign your paycheck, you’ll be serving them, not your readers. News cannot sustain the way Youtube does. It is far more important than that. Good science needs good journalism and good journalism needs our help.

www.newslaundry.com