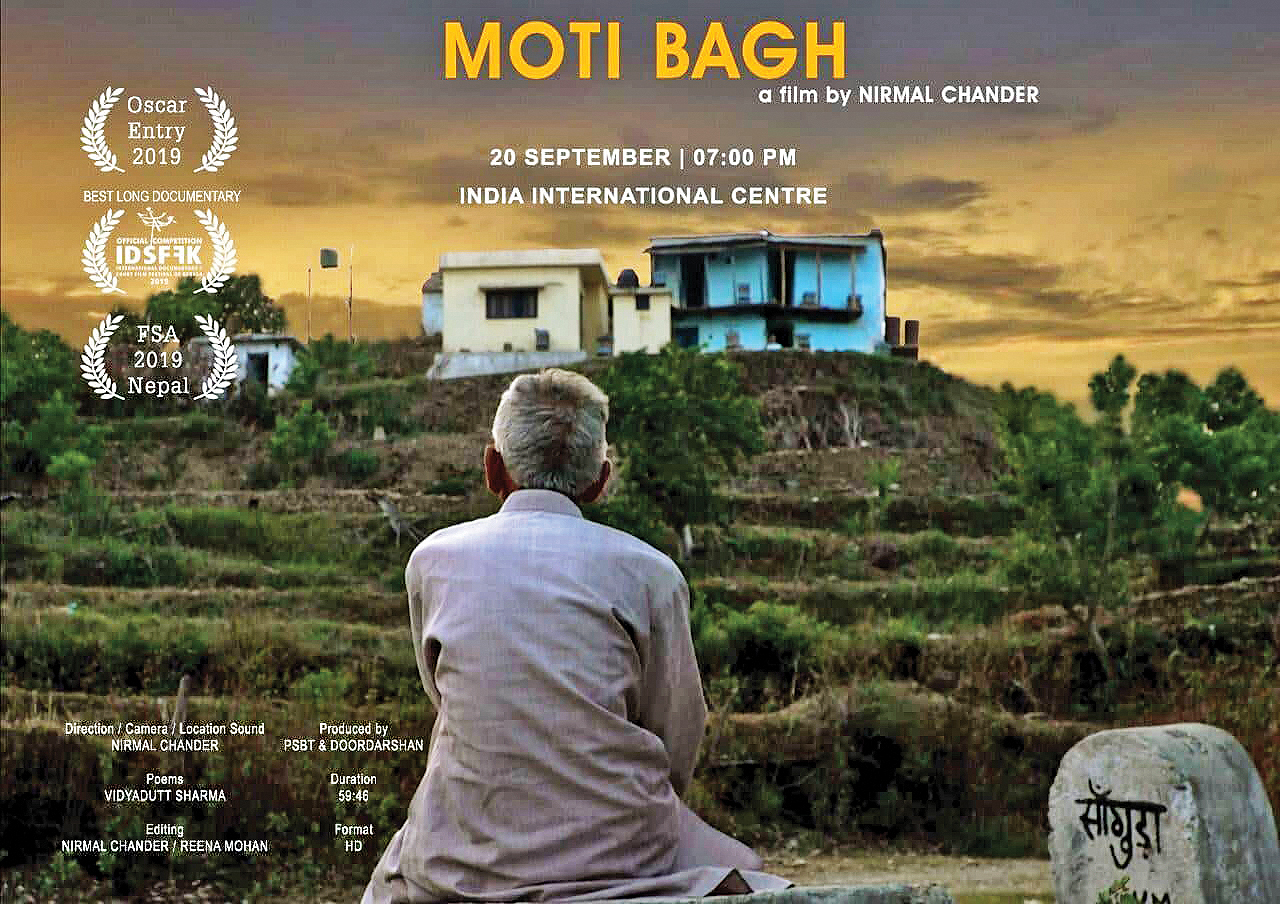

Nirmal Chander’s documentary Moti Bagh, based on the struggles of an 83-year-old farmer, has been nominated for the Oscars this year

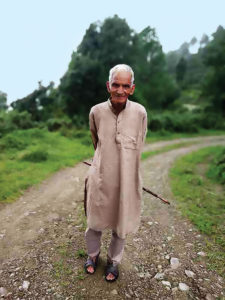

“So many hands in the kitchen, and one in the field – cannot be productive,” says the 83-old farmer. For more than five decades, Vidyadutt Sharma has been struggling to take care of his five-acre farm land in Moti Bagh — which is situated amidst 7,000 ghost villages – as the locals migrate in search of employment and a ‘better life.’ But he refuses to give up on his roots, hoping to bring back Moti Bagh’s lost glory.

The migration crisis in Uttarakhand’s Pauri district, from the eyes of this strong-willed man, is the subject of Moti Bagh. Directed by Nirmal Chander, the documentary has received a direct entry to the Oscars this year. Chander is an award-winning filmmaker who has been making documentaries for over two decades.

His family comes from Uttarakhand, giving him an intangible bond with the place. So, what brought him back to his roots? During his visits, he had no intention of documenting the ongoing migration crisis in the region. He believes his film addresses other issues as well. “Obviously, migration is a big issue, but so are environment, water crisis, food, security, animal menace and many more. So, it’s not just about one thing. They are all interconnected.”

Chander usually tends to approach his films through his characters — and what they are engaged with. “I don’t think like ‘this is the issue, and who will fit into this issue.’ Rather, here’s my character and what he’s engaged with,” he explains. The protagonist happens to be his uncle.

“So, if you look at my uncle, he’s not somebody who’s migrating – he’s a solution to the migration. I thought I don’t want to make a film only on migration but also about life there — and the way it’s being lived — honestly or forcefully, what you believe in, what you stand for. The film is also about that,” he muses. He was filming on and off with Sharma, but wasn’t focussed — as he was trying to figure things out while doing so. After he got financial support from Doordarshan and PSBT, he started filming and it took almost one and a half year to finish the documentary.

The filming process was an eye-opener for Chander, which still remains with him. He feels he started connecting with the rhythm of the place. Coming from a city — where everything is fast-paced, makes sense, or one has to pretend to make sense, the hills were quite unlike all this. There, nothing has to make sense, he believes.

“You also start re-thinking about yourself. So, all these things start reflecting in the way you shoot or in the way you address the issue. I hope that all these will come out in the film — that connection and warmth, not only with the characters but the surroundings as well,” says Chander.

His protagonist is much more than just a farmer. Sharma is a writer, an activist and a poet. He is dedicated, passionate, a driven individual who believes hard work never goes waste — it will give one a good night’s sleep, if not garner any other results. “Writing a book is an easy task, but to grow a tomato is not,” he says boldly in one scene.

Many shades of this strong-willed man have been perfectly captured by Chander. And being an articulate person, the farmer never shies away from voicing his opinion. Moreover, his poems – which have been sung by Sharma himself in the film, have been woven into the narrative. Talking about this, Chander says, “His poetry connects the social fabric around him — the caste equation, the environmental issues and more. I wanted to bring these forth through the character —so that it hits you hard, you understand the characters, their predicament, what they are engaged with and can relate to it,” the filmmaker explains.

This poetry, coming from the local milieu, tells a lot about the place, the people and the essence. In a scene, Sharma sings in the backdrop of a wildfire. Through his song, we come to know that they’ve heard doomsday will come and everything will be destroyed. “But what worse will happen? It’s already all gone,” the grief-stricken farmer sings.

Then there’s a poem he recites about his deceased wife, about how they’ve been there for each other during good and bad times. “From environment to emotions to social structure – these poems depict them all. Also, life will always be difficult but there’s always poetry in it. It’s about how you take it and make sense out of it,” says Chander with hope.

Another crucial character in Moti Bagh is Ram Singh — a man who assists Sharma in farming, and has been taking care of him for 18 years. He’s from Nepal, and now lives in the village with his wife and daughter. “For me, Ram Singh is a very important character because he was one person who came in from outside, found a life here, earned money to educate his kids and plans to build a life back in his hometown, whereas the locals are leaving.”

But Chander is quick to add that he has nothing against the villagers who migrate. “I am not questioning why people are leaving – it’s fine, it’s their choice. We, the city people, can’t sit here and say ‘No! you have to stay there and save the mountains for us whereas we’ll go there as tourists, just to have good time.’ But what I am saying is that Ram Singh is keeping your land and soil alive, is feeding you — but you still see him as an outsider.”

He is undoubtedly happy about Moti Bagh’s direct Oscar entry. “But I’m happier because more people are showing interest in it. And I think it’s an important story to be told, as we all know where farming stands in India, the state of farmers and how this profession has lost its glory. So, if it helps in spreading the word and people wanting to see it, then that’s what I find more exciting,” says Chander.

“Whatever happens at the Oscars, it’s okay — it’s a race, you are in it or out of it but people’s interest in it is good for my character and documentary,” adds the filmmaker, who seems unfazed by fame. Coincidentally, his next is about a legend who too was unfazed by fame till her last breath — classical musician Annapurna Devi — celebrating her life, work and the person she was.

“Especially in the world of instrumental music, which is male dominated – Annapurna Devi has a special place and standing, which no one has. Her story needs to be told to people because she was somebody who broke the whole image of a performer. A performer, for us, is somebody who wants claps and appreciation from the audience. But she shunned everything, and said ‘I don’t need all this. For me, music is a spiritual journey,’” concludes Chander.