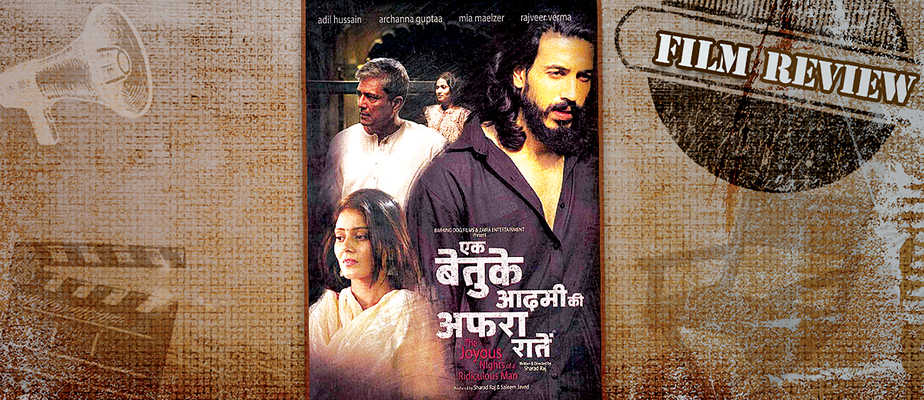

Ek betuke aadmi ki afrah raatein attempts to locate communal riots in a wider historical legacy of the nation state, while investigating individual stories of caste and subjugation through gender

Fyodor Dostoevsky is on a slow and laborious walk in Muzaffarnagar and Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. He notices another gentleman, Munshi Premchand, savouring the lives and detailing the quirks of its residents. They meet in an unpredictable twinning of alienation and angst in the independent film Ek Betuke Aadmi Ki Afrah Raatein (The Joyous Nights of a Ridiculous Man), written and directed by Sharad Raj.

The movie blends two short stories by Dostoevsky, White Nights and The Dream of a Ridiculous Man, with Premchand’s Bhoot. It’s an ambitious mix held together by two serious and, perhaps, insidious narratives of contemporary India — communal violence and caste.

The film is strong on commentary. It prefaces “love” and “post-modern alienation” with sex and violence. It also attempts to locate communal riots in a wider historical legacy of the nation state, while also investigating individual stories of caste and subjugation through gender.

Sharad Raj is a veteran television creative director and producer. This is his debut film, and it’s an ode to his muses during his days at the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune, ranging from Alain Resnais to Andrei Tarkovsky, Yasujirō Ozu to Ritwik Ghatak. In an email, Raj says, “I always start with an image. The mise-en-scène of the long take is something that naturally comes to me and that became the cinematic idiom for the film.”

A mix of elements that, on first sight, may be incongruous are brought together in a setting that is unhurried and slow. The film’s pacing seems to be a throwback to the many art films of the 1980s and early 1990s. Unfortunately, the “long take” is the film’s undoing. The story has a lot of heart and an emotional core which, if explored with better mounting and pacing, would have actually made for a more compelling experience.

Ek Betuke Aadmi Ki Afrah Raatein is about Gulmohar (a very wooden and raw Rajveer Verma), an alienated/post-modern character who runs a photo studio in Muzaffarnagar. Here he encounters the prostitute, Anita Muslim (excellently portrayed by Bangladeshi actor Mia Maelzer). They start a physical relationship which allows Gulmohar the chance to understand the subaltern voice of a woman twice suppressed — first as a Bangladeshi Muslim refugee in India and then as a prostitute with a child.

Anita is a complex character. She has a lover, Ajay, and is saving money to marry him, hoping to escape her binary oppression and live a decent life. Yet it is this love that eventually causes her death in the riots of Muzaffarnagar in 2013, where she’s betrayed by Ajay himself.

The Muzaffarnagar riots are contextualised in the film as a legacy. Starting with the communal violence of Partition in 1947 and during the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, the lives of poor Muslims, especially the women, are not so different even today. Unfortunately, the riots are merely a tangential plot device in the film. This takes away some of the immediacy and horror of such violence. Without the drama of action and reaction, the film is reduced to a tedious watch.

Unable to deal with Anita’s death and forced to address his own helpless anguish at not saving her, Gulmohar leaves Muzaffarnagar and takes to roaming the streets of Lucknow. Here, he encounters Gomti (Archanna Gupta), who is waiting for her lover to come and rescue her from a life of misery and entrapment. Gulmohar and Gomti relate to each other’s pain and desolation.

Gupta gives an effective performance as Gomti, a young woman seduced by her own stepfather (who also happens to be her brother-in-law). The stepfather, played by Adil Hussain, is a Dalit shoemaker and, in the course of the film, his character succumbs to the only power he is actually able to wield — the power to control his stepdaughter. When he is confronted with his incestuous behaviour and rejected by Gomti, he gives up his own life rather than lose his moral authority and power as her father and lover.

As a character, Gulmohar is deeply curious about the world. He constantly interacts with it through television, and even participates in the making of news as a photographer, but he is unable to relate to his surroundings. His alienation makes him the eponymous Restless Man. Yet, when the time comes, he chooses life and his engagement with it.

Ek Betuke Aadmi Ki Afrah Raatein is strong in its portrayal of small-town India and it raises important questions on the tight control over the thoughts and bodies of its young, especially women. It is also effective in highlighting the personal cost and horror of violence.

The film has been funded and produced through crowd-sourcing and has been screened at various film festivals. It will get a wider theatrical release in France soon.

www.newslaundry.com