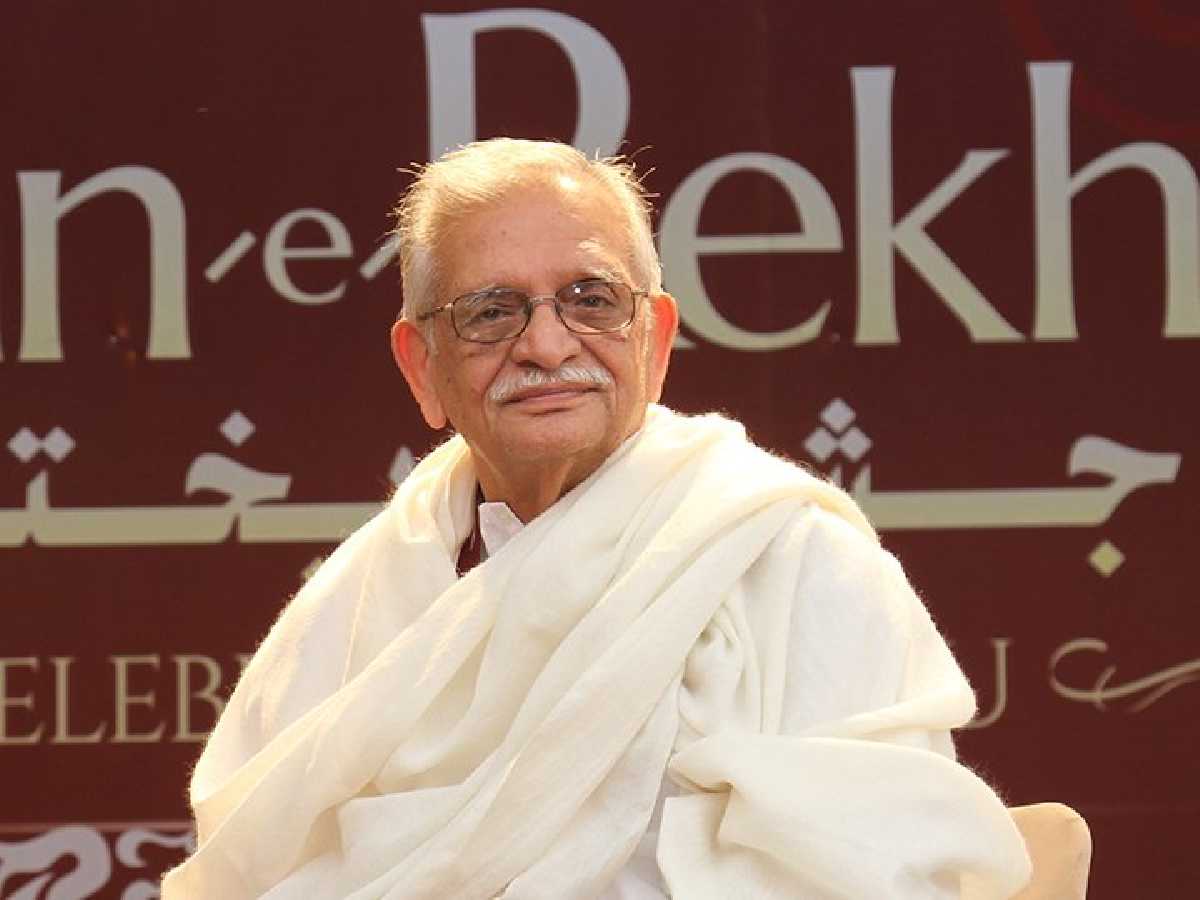

At the inaugural session of the tenth Jashn-e-Rekhta Festival, the hall fell quiet the moment Gulzar began to speak. He spoke as a man looking back at a work he believes destiny placed in his hands. The 1988 television series Mirza Ghalib, now widely regarded as the definitive screen portrait of the nineteenth-century poet, was almost a project that never happened. When it finally did, Gulzar felt the universe had already selected its Ghalib.

“I believe I was meant to make Mirza Ghalib with Naseeruddin Shah,” he said. He remembered how a young Shah had once written to him from FTII declaring himself the rightful heir to the role. “He had written, ‘You wait for me. I am coming to the industry.’”

A long-delayed dream

Gulzar’s affinity for Ghalib is rooted in his lifelong love for Urdu and Bengali literature. For years he had planned to make a feature film on the poet with Sanjeev Kumar.

“Sanjeev Kumar used to say, ‘I don’t need to listen to the script because I know you will not waste me,’” Gulzar said. The project collapsed when the producer withdrew funding. “It didn’t work out,” he added quietly.

The idea remained suspended until India’s television boom offered a new route. Gulzar realised that the episodic format would give Ghalib more space than a film ever could. “You can’t compress Ghalib into two hours,” he said.

The battle to cast Naseeruddin Shah

Gulzar first noticed Shah in an FTII diploma film and immediately recognised the “inner depth” needed for Ghalib. The producer, however, pushed for someone “more handsome”. Gulzar refused.

“I told him I need a good actor for this. And he will play the role very well.”

When the disagreement escalated, Gulzar made it clear he would leave the project if Shah was rejected.

The turning point arrived when Shah walked into a meeting and reminded Gulzar of his old letter. He also remarked, teasingly, that Sanjeev Kumar had once been “too fat” to play Ghalib. Then he delivered a blunt ultimatum:

“Do you think if I’m told I can’t play this role, I will let anyone else do it? I will take the fee I’ve asked for and do this role. Otherwise, I will not let anyone else do it.”

The producer was furious. Gulzar, however, saw exactly what he needed.

“I told him, ‘Babuji, this was Ghalib who just got up and left. This man has the attitude of Ghalib.’”

Shah’s portrayal went on to become a benchmark of literary biopics. Gulzar places it alongside Pestonjee and Sparsh. “I don’t see Naseeruddin Shah in these,” he said. “I only see those three characters.”

Sanjeev Kumar’s shadow over the project

The Rekhta session also revived memories of Gulzar’s long creative partnership with Sanjeev Kumar, whom he directed in Parichay, Koshish, Aandhi and Mausam. Gulzar recalled first seeing the young actor, then only twenty-three, playing a father in a stage production of All My Sons. Prithviraj Kapoor had been impressed as well.

“He used to complain, ‘Why do you cast me as an old man?’ But that is how we became friends.”

One memory from Parichay remains vivid. After filming a scene in which Kumar had to cough blood, Gulzar told him: “Hari, I am not a king or a Nawab, but I will give whatever you want.” Kumar replied with a smile: “Stop eating paan.” Gulzar did.

Kumar died in 1985, three years before Mirza Ghalib was released.

Poetry, loss and the language he returns to

The session also offered glimpses of the emotional landscape that shapes Gulzar’s work. He recited poems and spoke of childhood memories: never having seen his mother, carrying a lifelong “vacuum”, and being scolded for writing poetry even though his father secretly cherished seeing his name in print.

These reflections revealed the undercurrents that inform his writing, from longing and loss to affection and a meticulous care for language. Some stories, he said, “wait for the right moment and the right people”.

A life shaped by letters

Gulzar (born Sampooran Singh Kalra in 1934) is one of India’s most prominent Urdu poets, lyricists and filmmakers. Born in Dina (now in Pakistan), he moved to Bombay after Partition and worked various jobs, including painting accident-damaged cars, while writing for the Progressive Writers’ Association. Shailendra and Bimal Roy encouraged him to enter cinema, and he made his debut with the 1963 film Bandini, writing Mora Gora Ang Layle.

His collaborations with SD Burman, RD Burman, Salil Chowdhury, Madan Mohan, Vishal Bhardwaj and AR Rahman have produced some of Hindi cinema’s most enduring songs. Jai Ho earned him both an Academy Award and a Grammy.

‘Give me the life you’ve used’

Speaking about the relationship between a poet and their audience, Gulzar said: “Before the poems, I have a relationship with all of you. That’s why the poems are born.”

He recalled someone drawing a tiny plant on his cigarette case. “Come and see,” he said, “that plant has blossomed.” For him, poems grow from such gifted fragments of life.

Calling himself a “junk dealer”, he said: “Give me the life you’ve used. Give me the moments you’ve lived. I’ll take them.”

He then recited lines that held the audience still:

“Pick up the broken sleep of the night, collect the pieces of dreams that fell from the pillow.

Opening the folds of your turns and keeping them fixed, that is my job.”

Where wounds hide in words

“Many wounds are hidden inside rosaries,” he said. He added that he has hidden “many pains in thoughtful words” and that poems protect him from vulnerability.

“I’m sitting wrapped in poems. Without them, I am naked from within.”

Audiences often search for reality in poetry, he observed. “The reality is what’s been delivered to you. The inner reality, that is what matters.”

Revisiting his own work, he joked, gives him “allergies”. “The dust of old thoughts rises and I sneeze for days.”

Yet old poems, he said, still carry “the scent of winter quilts dried in the summer sun”. He remembered an early metaphor about a street juggler. “When I was young, he seemed like God. And now, when I’ve grown up, God seems like a juggler showing his tricks.”

Gulzar admitted he rarely returns to his old notebooks. “Sometimes when I hear a poem in someone else’s good voice, I wonder, was it me who said that?”

With typical modesty, he added: “If I had even ten per cent of Javed Sahib’s memory, I’d be a more successful poet.”

A poet shaped by his people

To the audience, he offered a final thought about the give-and-take that shapes his writing. His poems, he said, are crafted from moments borrowed from others and returned transformed.

“You have so much. I just come like a junk dealer and pick from your life. I return to you boxes and bottles of junk life filled with poems.”