It is time that India starts paying off its debts and focuses on the truth to be told—one series at a time

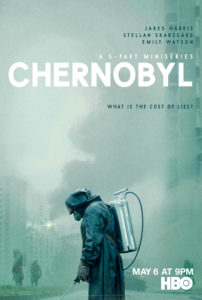

5-part mini-series on HBO

Aired on Hotstar in India

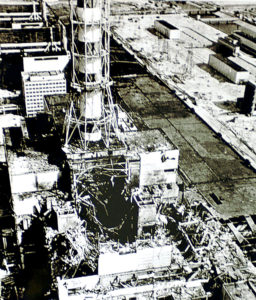

Just as the world was settling down to a life without the fantastic-and-gory Game of Thrones, HBO and Sky sneaked in Chernobyl, a devastating five-part mini-series about the 1986 nuclear disaster in then-Soviet controlled Ukraine.

Since May this year, the series has become the highest-rated show and a cultural phenomenon across the world. It is a brilliantly written, enacted, directed and produced TV series on one of the most devastating catastrophes the world has ever seen.

Chernobyl succeeds because it pulls no punches on what exactly happened in April 1986. Every detail and every emotion that the audience may be interested in has been captured effectively on screen. It is a disaster movie told as a procedural drama—a nuclear disaster: who done it?

The show is very stylised and evenly paced. The dialogues are excellent. There is pathos and poignancy, but there is no melodrama. Ever. The production design is brilliant and true to the period, apparently, the Russians have certified its authenticity even though they have questioned the central narrative and are apparently making their own version of the “truth” of Chernobyl.

What is interesting in the show is the human element of a catastrophe that had no precedent. In times of trouble or disaster, every kind of human behaviour is on display—the timid, the heroic, the lovers, the decision makers, the victims and the plain ignorant and the arrogant. They are all characters in the show.

The key to Chernobyl’s resonance and possible longevity is to serve as a cautionary tale. We would all be well advised to look at our own disasters, relief protocols and responses to quickly understand how to minimise damage and human casualties—especially if there is no precedent to fall back upon.

In India, there have been calls to make a similar show on the Bhopal Gas tragedy that preceded Chernobyl by two years.

On the intervening night of December 2-3, 1984, poisonous gas leaked out from the factory of Union Carbide in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, killing lakhs of people—the many unaware sleeping in their homes. The political, bureaucratic and corporate response of the Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation (UCC) management at the time mirrors that of the controllers of the Chernobyl plant in 1986.

For every Dyatlov at Chernobyl, there is a Gupta in the UCC. For every Brukhanov or other Party Apparatchik, there is a Chief Minister or his aide, a venal politician beholden to party leadership and corporate sponsors in Bhopal, and for every Legasov, there is a journalist Motwani or a safety expert Roy, as shown in the film Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain.

The parallels between the two situations and their responses are extraordinary.

The difference in the two situations, however, is that Chernobyl was a European, first-world nuclear disaster and the UCC gas leak in Bhopal was a South Asian, third-world industrial tragedy. While the former became a human challenge overcome by the world community, every cry for justice in Bhopal ends with procedural or compensatory negligence till date.

As many as eight films—features and documentaries—have already been made on the Bhopal gas leak so far.

Only two of these films were made by Indians. Bhopal Express by Mahesh Mathai in 1999 was the first feature film on the tragedy and remains the most accomplished. The second one was called Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain by Ravi Kumar, made in 2014.

The others were international documentaries: Bhopali (2001), One Night in Bhopal (2004), Twenty Years Without Justice (2004), Secrets and Lies (2007), The Yes Men Fix The World (2009), Litigating Disaster (2004). All looking at different aspects of the tragedy.

The irony of such a devastating tragedy not being documented well enough or exhaustively by the abundant Indian filmmaking talent remains a lacuna. So too is the access to these films—they are not easily available on any one platform.

There is scope, therefore, for an exhaustive, revealing and sensitive mini-series on the subject told with empathy and new narrative/production values that match international standards.

For broadcasters and OTT channels in India, Chernobyl is a lesson in taking a historical event, basing it on meticulous research, especially oral history told by contemporary survivors and using it to tell a cautionary and compelling story.

Towards the end of the show, in Chernobyl, the Soviet nuclear physicist, Valery Legasov says, “Every lie we tell incurs a debt to the truth. Sooner or later that debt is paid.”

This year in December, we will mark 35 years from the day the gas leaked in Bhopal. It is time that India starts paying off its debts and focuses on the truth to be told—one series at a time.

www.newslaundry.com