The disappointment with the film lies in its inability to actually engage with and address the issues arising out of small town Indian male fantasies and loneliness

“Ayushmann Khurrana’s Dream Girl is on a rampage. The film has minted Rs 16.42 crore on the second day of its release,” gushed India Today on September 15.

Just a day earlier, film analyst Taran Adarsh had tweeted: “#DreamGirl takes a heroic start… Emerges #Ayush-mannKhurrana’s biggest opener to date… Has also opened bigger than several mid-range films [2019] like #Uri [Rs 8.20 cr], #LukaChuppi [Rs 8.01 cr] and #Chhichhore [Rs 7.32 cr]… Fri Rs 10.05 cr. #India biz.”

Adarsh explained the footprints of this success on September 15, tweeting: “#DreaGirl witnesses superb growth on Day 2 [63.38%]… Circuits that were decent on Day 1 join the party on Day 2… Biz at metros, Tier-2, Tier-3 cities go on overdrive… Day 3 should surpass Day 2 by a margin… Fri 10.05 cr, Sat 16.42 cr. Total: Rs 26.47 cr. #India biz.”

The film is supposed to have been made at a cost of Rs 30 crore. Having released in 1,800 screens, it will be considered a hit if it crosses Rs 40 crore: a feat it seems well on the way to achieving within the first week itself.

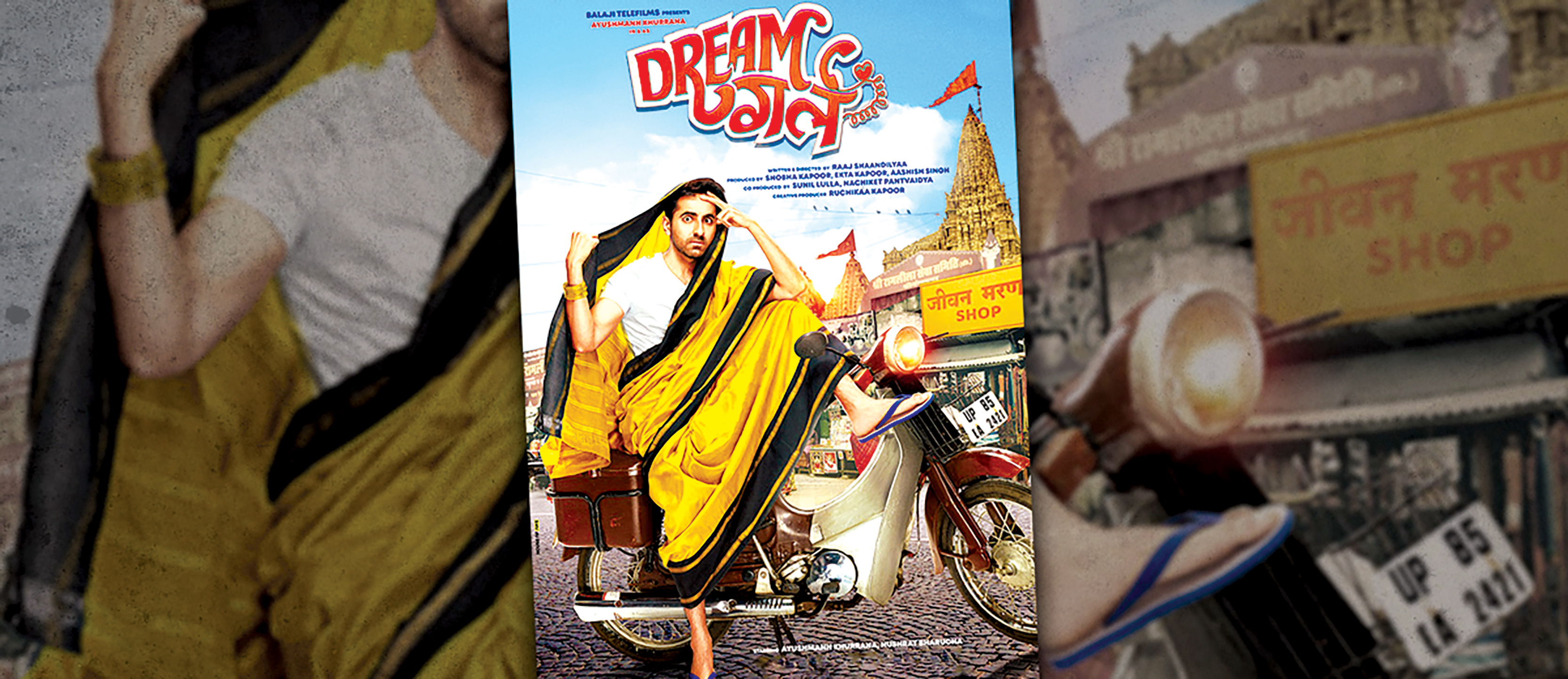

Given the publicity and posters of the film, one thought it was about male cross-dressing and the ensuing hilarity. Previous efforts were always a hit, be it Rafoo Chakkar (Rishi Kapoor), Chachi 420 (Kamal Hassan) or Aunty No 1 (Govinda). Cross-dressing has a long history in Bollywood and most leading men have done it. In fact, early Indian cinema only had men dressing as women to play the female parts as it was not considered a career option for women of good families.

However, Dream Girl is not about cross-dressing. The only time Khurrana does cross-dress is when he is playing the mythological characters of Sita and Radha in local stage performances for which he is treated with reverence in the town of Gokul (Mathura). Instead, Dream Girl is about a call centre where the unemployed Karam (Ayushmann) gets a job as “Pooja” for his ability to mould his voice into that of a woman. At the other end of the line are various men who are addicted to Pooja’s soothing voice and “friendly” chats. There is even a woman, Roma, jilted in love by a man, who turns to Pooja for succour.

The hilarity then is in the unravel as Karam/Ayushmann gets caught in his own web of seduction and everyone wants a relationship with Pooja. Some of the scenes are genuinely funny and there is a healthy dose of advice on love being a great equaliser and of appreciating and reciprocating the love of those we have in our lives rather than those we fantasise about. Between these complexities is a romantic track with Mahi (Nushrat Bharucha) who is willing to stand with her man as the climax upends his identity as Pooja.

The film is written and directed by Raaj Shaandilyaa making his debut as a director. Ayushmann is effortless and so are his co-actors, especially Annu Kapoor and Vijay Raaz.

The disappointment with the film is in its inability to actually engage with and address the issues arising out of small town Indian male fantasies and loneliness. It would have been a brilliant film if Shaandilyaa had even touched on the lives of the others at the call centre: Pooja’s colleagues, all of whom are women. It would have also been interesting to see the playout of the fantasies, not all ending in marriage with Pooja but contextualised in the socio-economic and political environment of the fictional town of Gokul (Mathura). All these could have been moulded into a satire instead of ending up as a simple slapstick comedy. It’s like eating poha without that extra dash of lemon or chole bhature without the onion and green chilli.

On Quora a few years ago, a user named Navin Kabra wrote: “…by and large, it appears that Indian men are pretty simple as far as sexual fantasies are concerned. From the report (of a survey conducted by India Today), we find out this—most men in small towns will remain virgins until they get married. Their spouse is their only sexual partner and if she is ready, they are satisfied. Surprisingly, their ideal sex partner is their spouse and not some film star or sportsman.”

Similarly, writing about young love in small town India, Santosh Desai says that during a research project in North India, he found that love and crushes were openly admitted even if they were considered out of bounds of possibility: “It allows the mind to explore possibilities that the body cannot and in doing so, it opens up pathways in the imagination that might otherwise have been stifled completely … The crush lives in an intermediate space between fantasy and experience, the commonplace and the taboo, the inconceivable and the impossible.”

This is the theatre and premise of Dream Girl. This is also the space where Dream Girl flounders because the climax unravels in a speech about loneliness and acceptance but it conveniently glosses over what Desai calls the pace of change in small town India: “Like many other things in India, change comes slowly, and in a covert and muted form. The radical comes hidden within the apparently mundane. Changing a system that is intricately organised so as to keep things in place requires stealth and time. In doing so, both sides find their own victories—things change while they remain the same.” No easy solutions here.

It is understandable that the filmmaker wanted to keep the content simple and cute for a family audience but it is this very audience which is being addressed through the fictional town of Gokul (Mathura). A more nuanced telling could have also been a takeaway for them to understand and appreciate change and bring acceptance in its wake.

The fact that Ayushmann Khurrana has become a flag-bearer of the niche and yet mass world of middle class India means that we are going to see a lot of unconventional films from him. Next up are Bala about premature baldness and Gulabo Sitabo about two warring puppet sisters-in-law whose shows become redundant with the advent of computer games and TV. It is exciting that such films are getting traction and making money at the box office but once the euphoria about the niche becoming mass or the mass becoming niche settles down, we can only hope that filmmakers will also address the nuances of these issues and not just focus on the uniqueness of the ideas.

Not since Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s films have we seen the fun and frolic of the Indian middle class. One can therefore be hopeful about the slice-of-life genre being revived with a whole new generation of ideas, filmmakers and audiences.

www.newslaundry.com