How popular songs in Bhojpuri legitimise sexual harassment.

Earlier this month another case of a viral video of a girl being molested in Nalanda district of Bihar was reported. Within a span of three months, it’s the third such case. Earlier videos of girls being molested in Jehanabad and Gaya went viral in April and May, respectively. Even seen with resigned indifference to everyday crimes, the nature of these cases reveal something more. Their point of departure lies in the fact that they show the stretching of the public sphere as the site for display of sexual violence.

In a state where sexual harassment has been generally cloaked under the charade of public posturing with respect for women, recently there have been definite signs that this brazen show is now becoming a competitive arbiter of social clout. One way to look at it is to see its grotesque legitimisation in current popular culture.

Have there been recent indications in popular culture in Bihar — particularly in the realm of male revelries — that have turned certain forms of sexual harassment into competitive demonstrations of social power? If we take the pop music scene in Bhojpuri, one of the five languages—Maithili, Magahi, Bajjika and Angika are the other major languages and dialects spoken in the state — the answer isn’t difficult.

The Bhojpuri pop music industry—the appeal of which cuts across all parts of the state and neighbouring Jharkhand and eastern UP—has been coming up with songs that sound like anthems for the claims of different social groups for harassing women.

Using castes or caste-revealing surnames as social claims on women, the songs tend to valorise caste-empowered sexual misconduct. As with all inter-caste rivalries, this has triggered a dubious race among different castes to have such a song written and sung, validating their claims.

Often performed as dance numbers in orchestra— generally with all-male attendance—the raunchy lyrics validate the right of caste groups to harass women dancers and, by extension, other women too. Sample different versions of chartbusting songs whose lyrics are a mix of khari Hindi and Bhojpuri.

Cheerleading the harassing exploits of “Babu Saheb” (a sobriquet used for Rajputs in Bihar, Jharkhand and eastern UP), the popular number has the key line: “Babu saheb ka beta hai, stagewe par chumma leta hai” (He is Babu Saheb’s son, he kisses on stage itself).

If other castes felt left out of this competitive right to harass, the song has been followed by at least three versions. For Brahmins, the lines are: “Pandey Ji ka beta hai, chumma chipak ke leta hai” (He is Pandeyji’s son, kisses while holding you tight).

The influential landlord caste Bhumihars (mostly having roots in Bihar and eastern UP) have been appeased with a version which celebrates abduction as well, as the lyrics go: “Hayeen dabang Bhumihar, utha le jayem jabari” (I am the strongman Bhumihar, [I] will abduct you forcefully).

But that doesn’t mean that such brazen musical statements are restricted to the upper castes. The Yadavs have a version in their name, as the song goes: “Yadav jee ka beta hai, jahan man kare wahan chumma leta hai” (He is Yadavjee’s son, he kisses wherever he wants).

Much before caste identities were used in musical assertions of sexual harassment, a popular Bhojpuri number celebrated the impunity that comes with something cutting across caste lines: political power. The song was echoing the licence, which even family members and associates of elected leaders flash, while treating their constituencies as fiefdoms to harass.

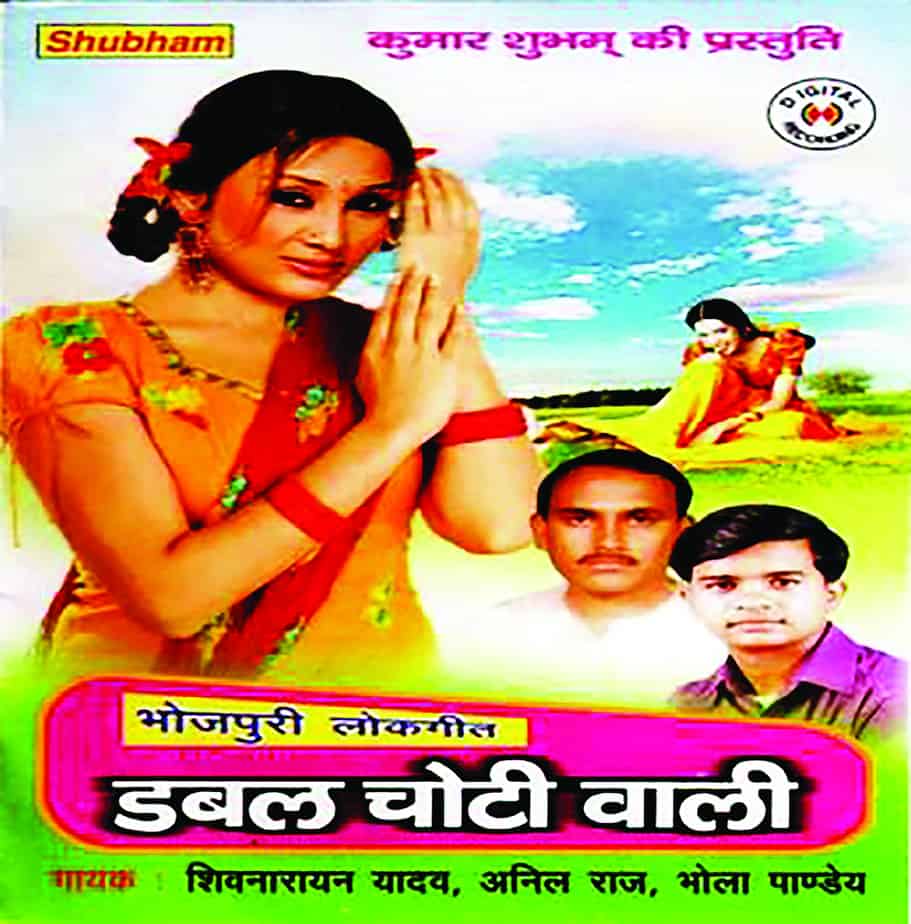

This criminal sense of entitlement that political patronage to crime brings can be felt in this 2008 number. The song opens with these lines: “Kaka hamar vidhayak hawue, na derayeim ho, O double choti wali tohke taang le jayeim ho” (My uncle is an MLA, I fear nothing. O double-braid girl, I will abduct you).

A definite tinge of sadness, laced with nostalgic lament, creeps in when one juxtaposes contemporary Bhojpuri pop music scene with times when Bhikhari Thakur enriched Bhojpuri folk music, theatre and art. However, with all its vulgarity and bawdy imagery, the matrix of social power reflected in these songs expose fault lines which have been part of sexual exploitation in the region.

Writing in Republic of Bihar (Penguin, 1992), Arvind N Das identified women as staple casualties in the pattern of the production of violence in Bihar, particularly rural Bihar. He wrote, “Indeed sexual oppression is a significant part of class oppression in Bihar. So much so that when landlords organise gangs to carry out gohar, they include at least a few people who are known rapists.”

In a way, these Bhojpuri pop songs mirror the deeply entrenched notions of social power, in which women can be claimed as one of the entitlements. For all practical purposes, for women at the centre of such musical assertions, life is still “short, brutish and nasty”.

www.newslaundry.com