Why did a film chronicling the life of India’s most celebrated cricketer Sachin Tendulkar fail to leave a lasting impact?

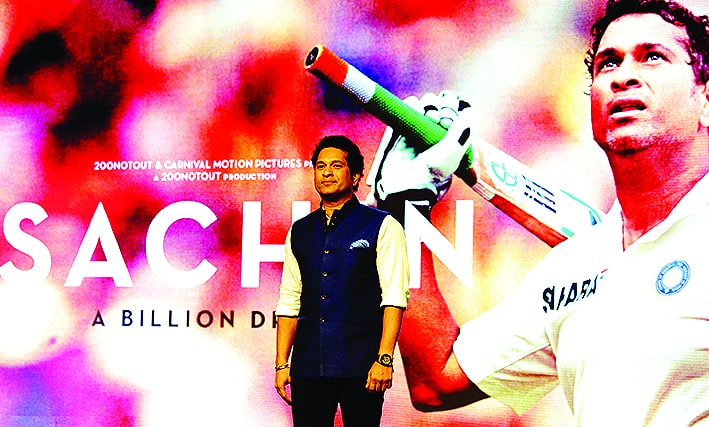

Exactly a year after the release of James Erskine’s ambitious docu drama Sachin: A Billion Dreams, jury is still out on why did the film chronicling the life of one of India’s most celebrated icons didn’t leave lasting imprint. Was it limitation of sporting documentary as a new genre for Indian audience? Or was there something about the carefully cultivated persona of the film’s subject itself which didn’t let Erskine foray into aspects which would have made it a more engaging narrative?

With benefit of hindsight, one may now see that perhaps Erskine couldn’t overcome the awe that clouds anyone seeking to tell the larger-than-life Sachin story.

Three years before the film was ready for release something should have warned director James Erskine that his new muse wasn’t the cinematic material that the life of a flawed cycling icon had been for his documentary Pantani: The Accidental Death of a Cyclist (2014). That was also the year when Sachin Tendulkar, arguably one of the most enduring legends in cricket, had come up with his autobiography Playing it My Way: My Autobiography (Hodder & Stoughton, 2014). While the book revealed nothing that fans didn’t already know, it reinforced what even his admirers, such as journalist and novelist, Manu Joseph conceded they always knew about him, “He carries within him the fear that makes men good, the fear of being seen as bad.” In denying people untold aspects of his 24-year-international career, Tendulkar ‘s autobiography had failed George Orwell’s test for judging autobiographies — “an autobiography is to be trusted only if it reveals something disgraceful”.

That’s one of the problems with Erskine’s almost two-and-a-half-hour long biographical documentary film Sachin: A Billion Dreams — it ends up as a visual extension of the icon’s autobiography. That’s a risk you incur when you seek the support and involvement of the subject too much in the project, as was evident in the hagiographical nature of two sports biopics which were released in 2016: Azhar and MS Dhoni. The danger was lurking somewhere as you saw Tendulkar on a promotional overdrive for the film. Despite offering far superior production values and narrative finesse of a documentary, the film doesn’t manage to escape that trap.

However, using a non-linear narrative, the film isn’t devoid of its moments. It benefits from access to the legend’s family videos. It also showcases that the batting maestro can be very articulate when he chooses to be, especially when he evocatively recalls his bond with his father and the pain of losing him in the middle of his illustrious career. It’s striking that he struggles with absence of his father with a feeling which is more likely to agonise late bloomers rather than child prodigies like him — the fact that the father wouldn’t be there to witness what they achieve in later phase of their lives.

After a point, such collage of family memoirs become cloying, partly because they have already been repeatedly served for public consumption in India over the last two decades of Tendulkar’s conquest of public imagination. Here you get a feeling that Erskine is playing the role of India columnists for The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal — producing primers to understand and interpret India for foreign media consumers.

Perhaps realising that what the documentary has in name of a narrative is already popular history, the film succumbs to the temptation of linking it to pop-sociology and clichéd tales of post-liberalisation India, even sneaking in the subtext of post-Independence chronicles of a poverty-stricken young republic. So you have the coincidence of Tendulkar’s rise with the influx of money in Indian cricket through global telecast rights and leading brands lining up to woo popular cricketers for endorsement of their products. Such exercises in appropriating cricketing tales for larger social analysis have been a convenient tool in hands of writers and academics alike since CLR James wrote the classic Beyond a Boundary (1963), or closer to home, Ashis Nandy’s The Tao of Cricket (1990).

It, obviously, invades the film with stereotypes — you cringe when Harsha Bhogle says how Tendulkar imbibed middle class values of humility. If Bhogle is meeting people from middle class India anymore, he would like to reconsider his association of humility with middle class or for that matter, glorification of humility as a key virtue. In public figures, humility usually is a defence mechanism to guard against revealing their real selves — a feeling people often have while watching Sachin’s public interactions.

Similarly, shots of people of different religious groups and regions are a tad repetitive and perhaps designed as ready reckoners of India’s diversity and hackeyened ‘idea of India’ for foreign viewership.

Having the subject of the documentary as its key narrator may only be blessing if the subject is willing to go beyond the obvious. It would have been interesting if Tendulkar’s maudlin harping on about ‘team’s interest’ was countered with his sulking over missing a double hundred when Rahul Dravid declared the Indian innings in the 2004 Multan test match against Pakistan. For that matter, Tendulkar’s response to the constant criticism about delaying his retirement in pursuit of personal milestones would also have added to viewer’s experience.

There are too many reverential voices in the film that makes it creak under the weight of its uniformly awestruck tone. A slightly more critical look would have shown Erskine that hostel rooms and the cricket addas of Tendulkar’s playing days were also filled with what the film would consider blasphemers- critics. So, when the film celebrates a ‘billion people’ worshipping him or praying for him, it obviously has not mapped pockets of dissent, or heresy. In fact, much like pantheon of deities in India, there were substantive followings for other Indian and even international players, ranging from Rahul Dravid and Brian Lara, sometimes to the exclusivity of Tendulkar. People, as usual, are a vague entity — Tendulkar was the prime claimant but loyalties were still divided in India.

The multiples voices Erskine has assembled, however, reflect something else as well. Many international players and cricket commentators had figured out that with India emerging as the hub of world cricket and Tendulkar the ruling deity, ‘quotes-about-Sachin’ would be in demand in Indian media houses. So the rent-a-quote phenomenon in Indian media spawned to coverage around Tendulkar too. You had everyone with something to say about Tendulkar, often adding to the echo-chamber of adulation. Those who didn’t were either vilified or discredited — see how the film demonises Greg Chappel. It’s something that has outlived Sachin, as evident in reactions to English swing bowler James Anderson’s comments about the current blue-eyed boy of Indian cricket Virat Kohli.

If the thematic thread running through the film is Tendulkar’s quest for the World Cup, what the film misses is what cricket fans in India experience in different ways — cricket had changed far too much during the 24 years of his career for people to attach the same importance to the event as they would have in, say 1990s. Tendulkar was beneficiary of post-1982 surge in television viewership. The national expansion of television network coincided with India’s World Cup triumph in 1983 — taking the game, colonial amusement of primarily Commonwealth countries, to the homes of hinterland India with a hope of national glory.

However, by the time Tendulkar got his hands on the World Cup in 2011, the overkill brought by excessive cricket, and perhaps multiple entertainment avenues of digital age had reduced cricket to a ‘passive habit’ rather than keen involvement. That’s what ad man and social commentator Santosh Desai offers as one of the reasons while probing the question why Kohli will be admired but not loved the way Tendulkar was. His absence from international T20 cricket, perhaps to prolong his career, was also something the film could have addressed.

The fact that the film hasn’t been able to break Tendulkar’s cagey approach to talking about the cricket betting scandal that rocked Indian cricket in late 1990s and by the turn of this century isn’t surprising. His utility as a witness to key developments within dressing room and as a former captain hasn’t been leveraged partly because of his reluctance to go against the establishment and perhaps because of what he says in the film “ I don’t know enough to say anything with any kind of evidence”.

However, this aspect of having stakes that are too high in the establishment to risk saying anything courageous has been disappointing to many, and as has his guarded approach to taking stands on public issues. The film has a clip of Brian Lara comparing Tendulkar to Muhammad Ali — but he lacked Ali’s willingness to comment on issues of public concern.

Indian audience can still wait for the coming of age of sports film genre in the country, this isn’t certainly one of them. Erskine’ effort, however, is certainly an improvement over the mediocrity of sports flicks of last year. One may concede that he was partly constrained by the meticulously cultivated public image of his subject where access to the more interesting personal space is still forbidden. Curiously, Erskine’s film on Pantani also bordered on eulogy even when the subject was dead.

In identifying, however, with the dreams that the film tries to share with a billion Indians what shouldn’t blind anyone to is the reality that a present cricketer’s international career would have finished after the initial failures that Sachin had as 16-year-boy making debut in Pakistan. That’s something that inspirational films don’t tell, and need not tell- the world outside the theatre isn’t that kind. That perhaps, also explains why such films get made — offering the escapism of someone who is too perfect to be true. There are times, however, they get too far to resemble anything around.