The week-long inaugural edition of the Khelo India Para Games held in the Capital from December 10 to 17 turned out to be a good platform for aspiring para athletes aiming to test their skills ahead of the challenging 2024 season that will also feature the Paralympic Games in Paris.

“Having more events at the domestic level for disabled athletes is a big advantage. It will encourage more people to come forward to support the para movement in India,” said Satyapal Singh, a Dronacharya Awardee. “More awareness ahead of next year’s Paralympic Games is a healthy sign.”

The Indian contingent won 19 medals at the 2020 Tokyo Paralympic Games held in 2021, and the Delhi-based Singh was hopeful of a better tally at the 2024 Paralympic Games.

“Due to better preparation this time, the medals tally will certainly swell in Paris,” Singh added.

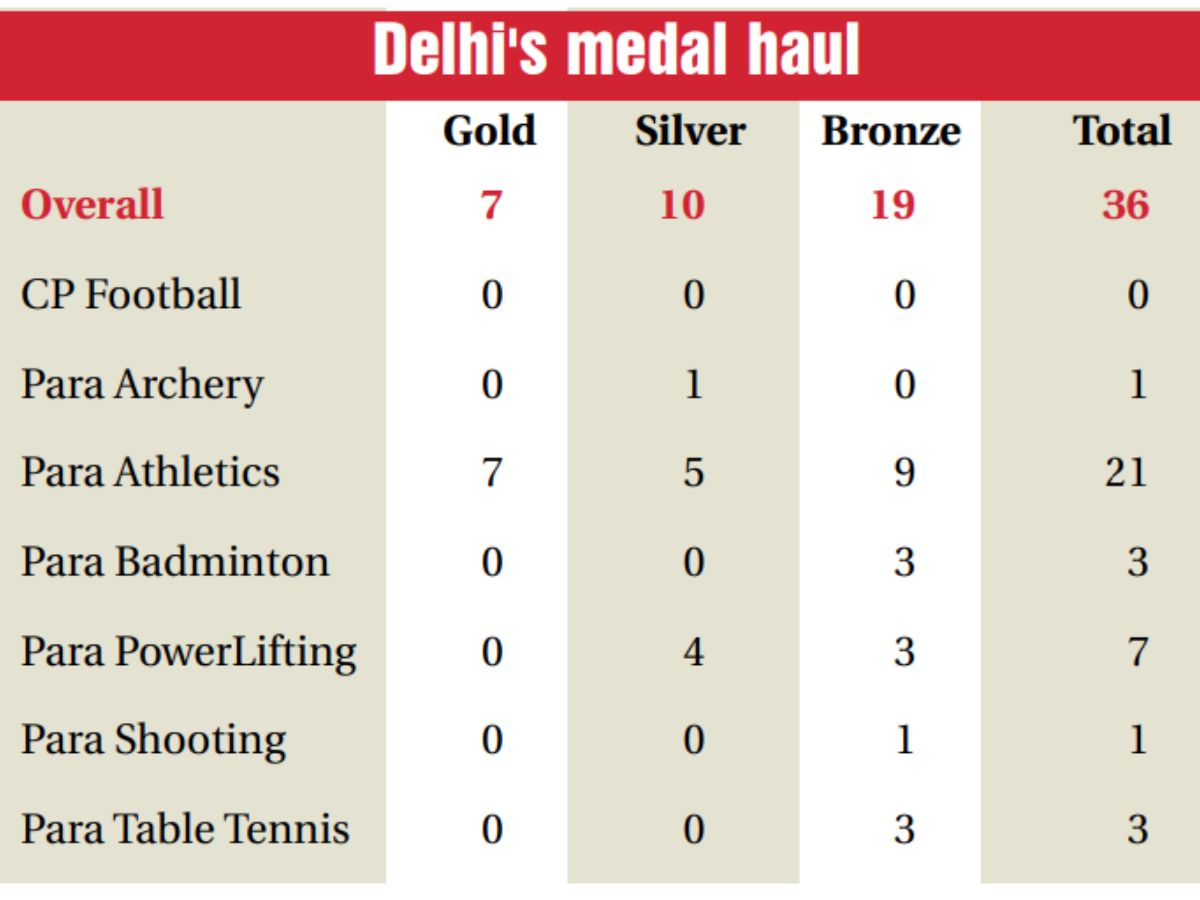

The inaugural edition of the Khelo India Para Games saw as many as 1,450 para-athletes compete in seven disciplines from across the country in their respective categories. While Haryana won the overall title with 105 medals (including 40 gold, 39 silver and 26 bronze medals), the Delhi contingent finished eighth with 36 medals, seven of them gold. The Delhi team also won 10 silver and 19 bronze medals. The lion’s share of Delhi’s medals – 21 out of 36 including all seven gold medals – came in para athletics.

The competition was conducted in seven disciplines, including athletics, shooting, archery, football, badminton, table tennis and powerlifting.

Based out of Delhi, Harshita Tate who competes in T37 category in sprint events, including 400m was excited to be part of the Khelo India Para Games. “It was a good opportunity to compete in the off-season,” the 23-year-old said.

Harshita was seen having good support from her friends, who were encouraging her during the event. She finished fourth in the 100m and won bronze in the 200m though her favourite event — 400m — was not in the programme.

“I train with a group of [able-bodied] athletes, who are very helpful. They don’t let me feel lonely and support me. That keeps me going,” Harshita revealed.

At next month’s National Para Games in Goa, Harshita will also incorporate long jump in her schedule. “The competition in Goa will be an excellent platform to test my skills,” said Harshita, whose personal best in long jump is 3.2 metres.

The Paris Paralympic Games qualification mark in her category is 3.8m. “I have a better chance of qualifying for the long jump,” she asserted.

With support from government and private sponsors, the para sports movement in the country is growing, Singh said. “Disabled athletes are also getting opportunities to come out and play,” the coach said.

Para-athletes like Harshita, who quit her medical course in 2021 to pursue excellence in para-sports, portray fighting spirit.

“I want to prove myself,” said Harshita, whose parents have a small business venture in Bengaluru.

“I am from a middle-class family. I have goals to achieve and not go back to Bengaluru until I’m successful in my venture,” Harshita added.

According to Harshita, there should be more awareness about differently-abled athletes in the country. There should be better medical facilities and a good recovery system post-exercise.

“Understanding the disability of an individual is what is important,” she said.

“Instead of announcing big cash incentives, the respective state governments should focus on having better facilities for disabled athletes at the grassroots level,” Harshita added.

“It will build a good foundation for the future.”

Hailing from a middle-class family and staying on her own in the Capital, Harshita said it was challenging.

“Given meagre resources, it’s tough to pursue sports for those para-athletes who are on the fringes,” she said.

Vipin Kasana, a former international javelin thrower and now coaching para athletes in the Capital, is of the view that the state government should have good policy to support para athletes.

“Job security is the key factor in development of para sports in India,” Kasana said.

Kasana believes that lack of patience among young para-athletes is one of the root causes impeding growth of para sports in India.

Reports prior to the 2022 Hangzhou Para Asian Games emerged that a Delhi-based visually impaired para athlete allegedly manipulated medical documents to compete at the Para Asian Games. He competed in the T13 1500m and won bronze. Later he was disqualified and his medal was taken back.

Wheelchair-bound Neeraj Yadav, who won two gold medals (javelin and discus) in F55 category at the Hangzhou Para Asian Games, failed dope test conducted by National Anti Doping Agency (NADA) prior to the continental games and might lose the medals.

According to reports, Yadav failed a dope test for anabolic steroid for an out-of-competition dope test in Bengaluru. If Yadav is found guilty, he could face a four-year ban for his first doping offence.

Kasana doesn’t rule out that some coaches misguide athletes for personal benefits.

“I do counselling twice a week, and advise athletes not to rush to earn fame as there is no short-cut route,” Kasana added.

Paul Fitzgerald head of World Para Athletics, who was in the Capital earlier this month said the world governing body has a strong system in place to check integrity of the competitors in para sports. “Some people see the benefits and try to cheat. But we try our best to advocate fair play,” Fitzgerald added.