Hollywood has realised the value — and profitability — of diversity in stories, cast and crew. India is not far behind

Bollywood might be inspired by Hollywood in multiple ways — from movie plots to the industry’s name itself — but when it comes to social diversity, Bollywood is oddly sparing. Diversity is not a popular subject in its movies, if at all. While the US makes an effort to study, discuss and comment on diversity and diversity issues in its film industry, India is largely silent.

In Hollywood in 2015, diversity and inclusion advocate April Reign created a storm on Twitter with the #OscarsSoWhite hashtag, pointing out that none of the Oscar nominees for the “Actor in a Leading Role” category were people of colour. The impact of the hashtag in subsequent years is unarguable; at the very least, it stirred conversations on diversity that weren’t confined to the Oscars.

A recent study on diversity and inclusion in Hollywood, published by the University of California, Los Angeles, analysed Hollywood’s “longstanding diversity and inclusion problem”, looking at the top 200 theatrical films and 1,316 broadcaster cable and digital platform shows in 2017. Noting that people of colour and women account for 40 per cent and 50 per cent, respectively, of the country’s total population, the study found that only two out of 10 lead actors in Hollywood films were people of color while only 1.3 out of 10 directors belonged to a minority, compared to their population ratio of 4 out of 10. “Minority” here includes African Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, Asians and LGBTQ communities.

Moreover, in contrast to India, the diversity discussion in the US goes beyond representation and nominations. In January 2018, the University of Southern California launched a database of entertainment journalists and critics from underrepresented groups after a study found there was a complete lack of racial and gender diversity among Hollywood film reviewers, which influences moviegoers.

Bollywood is years behind

So, what’s the scene in India?

Nearly 70% of India’s population comprises the unrepresented sections — Dalits, Adivasis, Other Backward Classes. Yet, Bollywood producing perhaps one story a year on this vast unrepresented population often becomes a cause for celebration.

This is why Neeraj Ghaywan, who directed Masaan in 2015 — perhaps the only Dalit director with a “mainstream” Bollywood movie under his belt — is trying to change the narrative.

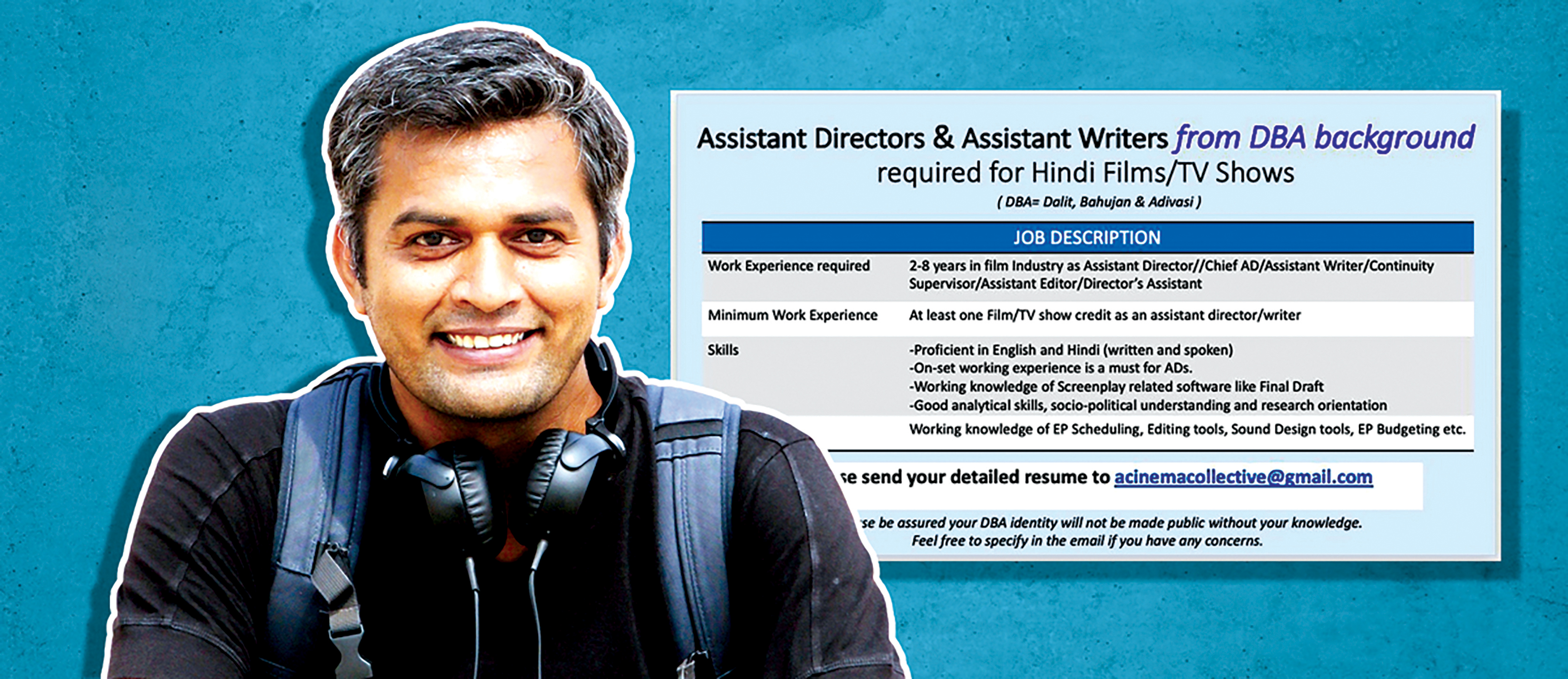

Last month, Ghaywan tweeted that he was looking for “Assistant Directors and Assistant Writers from DBA backgrounds” — DBA meaning Dalit Bahujan Adivasi.

Unsurprising, Ghaywan faced a flurry of criticism. Speaking to The Wire, Ghaywan said he was “amused at how ‘unprepared and uncomfortable’ the Hindi film industry is to discuss the caste realities of the country”.

He’s right. Bollywood not only lacks diversity in its lead actors, film crew, directors and stories, but even discussions around diversity are found uncomfortable. While Hollywood has its yearly diversity report, India has nothing. Every report or article on the subject points to a lone 2015 study by The Hindu on “lead characters” in Bollywood movies. The study found that the “overwhelming majority of nearly 750 actors and actresses who were in more than five movies over the last decade are upper caste Hindus, followed by Muslims”.

Diversity in Bollywood shouldn’t be opposed

The reluctance to diversify Bollywood’s stories, cast and crew seems to stem from the tired belief that Hindu Savarna stories with Savarna actors resonate with India’s masses. In a previous piece, I had studied Bollywood’s recent “small-town films” and found their storylines to be heavily dominated by Savarnas and upper castes. But the success of films with backward caste lead characters — such as Super 30, based on mathematician and teacher Anand Kumar — shows there exists a large audience for alternative stories too. Super 30 won critical acclaim and grossed over Rs 146 crore worldwide.

Then there was this year’s Article 15, which dwelt on the subject of caste discrimination and grossed Rs 70 crore at the box office in India alone. Though criticised for having a Savarna lead character, for a small-budget movie that had no songs, this is a definite indicator of success.

Similarly, Newton, released in 2017, was a critically acclaimed film with a Dalit character in the lead role who tries to defend democracy in a remote Adivasi village. Newton was produced by Drishyam Films, which also produced Masaan. Yet, Newton required a microscopic sort of analysis to understand the character’s social background.

And such movies come but once a year, and without any caste assertiveness seen in the stories based on Savarna characters.

Regional progress

Compared to Bollywood, regional cinema has been doing slightly better. In Marathi and Tamil, respectively, Nagraj Manjule and Pa Ranjith tell stories of Dalits, Adivasis and Bahujans. Both directors were also part of the Dalit Film Festival held this year in New York.

At the time, Ranjith — who shows Dalit assertion in Kabali and Kaala — described his connect with the Black Power movement in the US: “After having followed Black history and movies, I saw how Blacks fought to establish their literature, language and culture. I felt that I wanted to establish something like this. In Indian cinema and society, Dalits have no space and I wanted to create that space by showing Dalit empowerment.”

Ranjith has gone a step further following the successes of Kabali and Kaala; he produced films like Pariyerum Perumal and Gundu that gave other Dalit directors such as Mari Selvaraj opportunities to showcase their talent. Ranjith is also making his debut in Bollywood with a movie on Birsa Munda, an Adivasi freedom fighter who fought against the British when they tried to usurp lands belonging to the Munda community.

Amidst all this, Ghaywan’s call for DBA assistant directors and writers is a significant step in the right direction. This is how a movie’s cast and crew is diversified. Given that Bollywood has a lot of catching up to do, it could start with having directors and writers from underrepresented communities, followed by actors.

Once this happens, Bollywood might evolve to be on a par with its American counterpart when it comes to discussions on diversity in award nominations. The diversity of India’s population would finally be reflected in its stories. Big production houses can proactively hire actors and crew from diverse backgrounds and state governments can offer tax discounts to those who voluntarily adhere to diversity indices. This isn’t a revolutionary idea: several states gave Super 30 tax-free status since it was an inspirational story about the underprivileged. And this helped in its box office success. Profitability does matter, after all. Hollywood saw the huge commercial success of movies such as Black Panther and Crazy Rich Asians, showing the power of diverse images and stories on screen.

As Syrinthia Studer, Executive VP, Worldwide Acquisitions, at Paramount Pictures, said at this year’s Berlin Film Festival, diversity is “a necessity relating to consumers and how they consume their content, as they need to enjoy the content and see themselves on screen”.

So will the big bannaer producers and directors of Bollywood pay heed to Ghaywan’s diversity call? Ab ki baar, Bollywood thoda diverse kar do yaar!

www.newslaundry.com