To mark Jawaharlal Nehru’s 54th death anniversary, it’s interesting to analyse how Hindi cinema portrayed the leader

Independence had come at a time when the Hindi film industry had already emerged as the site of country’s cinematic expression in a language that was spoken and understood more widely than other languages in the country. That, however, didn’t mean that political themes lent themselves seamlessly to Hindi cinema.

They did that only in derivative ways — political subtexts embedded in generalities of social and family drama or even romantic tales. In that lies the difficulty of tracing political strands in the cinema of the period which immediately followed Independence. The political imprints that could be identified on the screen swung between maudlin optimism of a new-found national independence and the social reflection of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s idea of state-led economic transformation and modernisation.

It’s the latter which had more appeal as a commentary on experiments with the socialist model of nation-building in a young republic. Such intersection of cinema and Nehruvian policy also attracted the scholarly attention of economist Lord Meghnad Desai while writing his perceptive tribute to Dilip Kumar — Nehru’s Hero: Dilip Kumar in the Life of India (Roli, 2004). More on that later.

Before that, the first response was to see Nehruvian worldview as an extension of the ideological legacy of the freedom struggle. It became too sugary to sustain gripping political narratives. For instance, the visualisation of the Rafi number Hum laaye hain toofano se kishti nikaal ke song in Jagriti (1954) zooms in on Nehru’s photograph, as if it’s a cinematic address to the nation, while the lines go-“Dekho barbaad na ho ye bageecha, only to be followed by elements of Nehru’s pacifist international outlook: “Atom bammo ke jor pe aithi hai ye duniya, barood ke ek dher pe baithi hai ye duniya, rakhna har kadam dekh bhaal ke (world struts with the power of atom bombs, it’s sitting on a heap of gunpowder, take every step very carefully)”.

It was a lyrical statement of Nehru’s advocacy of disarmament in a polarised world where newly independent countries like India were grappling with the uncertainties of the Cold War. The statesmanship and undisputed nature of Nehru as a repository of the values the young nation was seeking could also be seen in the narrative of Ab Dilli Dur Nahi (1957) in which a boy is set on a journey to Delhi to plead the case of his falsely implicated father before Prime Minister Nehru.

But, amid the obvious afterglow of Independence, the sceptical scrutiny of the way the new republic was shaping up began finding expression on Hindi screen. While following the wave of Italian neo-realist filmmaking, Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zameen (1953) was a commentary on the plight of rural India stuck in agrarian indebtedness and the indifference of the state to rural distress, the socialist critique of urban India was obvious in Raj Kapoor’s Shree 420 (1955). One of the earliest takes on the scourge of corruption in public life could be seen in Footpath (1953) in which Dilip Kumar plays a journalist-turned-marketeer who returns to journalism to do an expose on the illegal trade. It asks disturbing questions about the distribution of wealth in the post-Independence India. Though the film is better known for the Talat Mahmood number Shaam-e-gham ki kasam, aaj ghamgin hai hum, the film made its way to film historian Avijit Ghosh’s book 40 Retakes: Bollywood Classics You May Have Missed (2013).

However, it was in 1957, a year after the Second Five Year Plan (1956-61) was rolled out with an emphasis on rapid industrialisation and public sector-led modernisation of production that BR Chopra’s Naya Daur sought to assess the implications of such policies on rural India. Though it showed its disruptive effects on a number of characters led by tongawalla Shankar (played by Dilip Kumar), it wasn’t dismissive about currents of modernisation like the introduction of machines and modern transport like buses for villagers. Despite the story revolving around man-machine conflict and rural-urban divide in the nascent phase of industrialisation, the final scene has Dilip Kumar’s character calling for mechanisation with a human face and consideration of rural needs. He argues that a middle path ensuring co-existence of man and machine was needed to change the fortunes of not only his village but the whole country. It’s simplistic and clichéd, but an earnest look at the policy implications of Nehruvian modernisation.

Far from being a critique of the nation-state, Naya Daur sought new patriotic language in fine-tuning our policy priorities, not merely replicating Nehru’s fascination for Soviet-style industrialisation. In doing so, however, the film had its nationalist heart in the right place. While the film would always be known for the Asha-Rafi duet Udde jab jab zulfe teri (a song rare in Hindi cinema for the open expression of a woman’s admiration for a man’s looks), it must also be recalled that it had youthful patriotic number Ye desh hain veer jawano ka (perhaps its boisterousness has strangely ensured that it’s played in baraats across North India). In sync with the policy initiative of rural community development, the film had a song to promote community work culture- Saathi haath badhana.

In some ways, Naya Daur drew the cinematic contours of India’s early experiments with central planning and Dilip Kumar echoed the debates which Nehruvian India was having with itself. Lord Desai observes, “As the 1950s saw India change from a skeptical, beaten nation to a confident player on the world stage, and then again into a defeated one by the time of the India-China war, Dilip Kumar mirrored the facets of these transformations. Footpath, Naya Daur, Ganga Jamuna and Leader show this movement from darkness to sunshine and then the beginning of a new disappointment as the 1960s arrive. Naya Daur is a quintessentially Nehruvian film.”

1957 was also the year when the counter-narrative to post-independence patriotism emerged in a song Sahir Ludhianvi wrote for Guru Dutt’s classic Pyasa. Sahir mocks the patriotic elite as Rafi hummed Ye kooche ye neelam ghar dilkashi ke/ ye loot te huwe caravan zindagi ke/ kahan hain muhafiz khudi ke/ jinhe naaz hai Hind par vo kahan hai (These streets and these intoxicating auction houses/ these robbed caravans of life/where are the protectors of pride/where are those who are proud of India).

Next year, Sahir returned to pen a satire on Iqbal’s patriotic verse Saare Jahan Se Achcha in Raj Kapoor-starrer Phir Subah Hogi (1958). Rendered by Mukesh, the song confronted the patriotic fallacies after a decade of Independence, as Sahir wrote- Chiin-o-Arab Hamaaraa/ Hindostaan Hamaaraa/ Rahane ko Ghar Nahii hai, Saaraa Jahaan Hamaaraa (China and Arab are ours, Hindustan is ours/ There is no house to live in/ All the world is ours). Taking a socialist dig at the supposedly socialist political order, the song goes on to add- Jitni bhi buildingein thin, Setho ne baat li hain, footpath Bambai ke hain aashiyana hamara (The rich have distributed the buildings among themselves/ the footpaths of Bombay are our homes now.)

While the themes of feudal stranglehold of landlords, moneylenders and rural poverty were woven in social melodrama of Mother India (1957) and Ganga Jamuna (1961), films like Boot Polish(1954) and even Awara (1951) had the subtext of wide economic disparities that defined life in urban India. That, however, didn’t go to the extent of making an overt political statement of angst or disillusionment.

Despite the emergence of counter narratives, Nehruvian modernisation continued to hold sway over the aspirations of the young country. Juxtaposed against the regressive feudalism, the call for building a modern country and vibrant economy still captured the imagination of filmmakers as well as lyricists. As India entered 1960s, Ram Mukherjee’s Hum Hindustani (1960) found virtue in Nehruvian project of industrialisation and scientific orientation for keeping pace with a rapidly changing world.

Prem Dhawan’s popular lyrics for the song, filmed on Sunil Dutt and rendered by Mukesh, has a visual collage of the country’s landscape marked by dams, power grids, heavy machinery, roads and modern transportation. The song Chhodo kal ki baatein, kal ki baat purani could be easily the theme song of Nehru’s vision. In fact, the visualisation of the song shows India’s first Prime Minister attending what seems like a Congress plenary session.

Four years later, the bruised morale of the nation following the defeat in the border war against China (1962), was partly soothed by Chetan Anand’s war classic Haqeeqat (1964). Though an overtly patriotic war film, its political communication is premised on the fact that it was produced with assistance from the Government of India and was an effort to restore the confidence of the country in its own strength and that of its leadership. With outstanding performances and immortal music, the film captured the imagination of the country. Its most popular number, Kar chale hum fida rendered by Rafi and written by Kaifi Azmi, has footage of Nehru visiting soldiers at the border posts.

The film uses a number of characters to portray the valiant resistance put up by Indian soldiers against Chinese troops in Ladakh sector, though it had nothing to say about the fate of Indian soldiers in Arunachal Pradesh (then a part of the erstwhile North Eastern Frontier Agency).

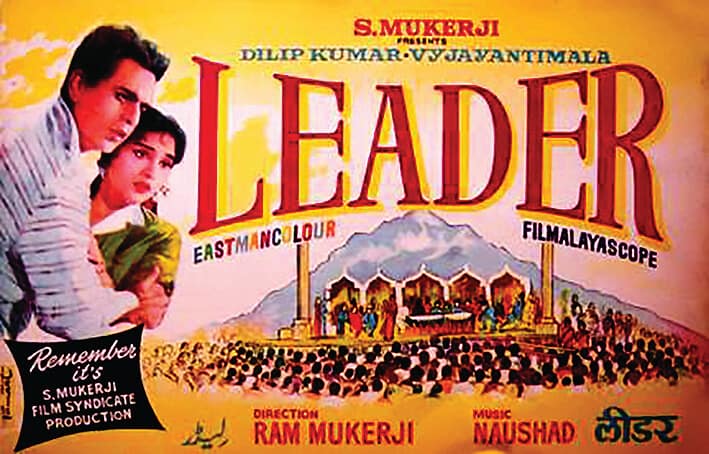

Two months before Jawaharlal Nehru passed away, the theme of politician-criminal nexus surfaced in Dilip Kumar-starrer Leader (1964). Perhaps that was a sign of the narrative that was going to occupy political filmmaking in Hindi cinema for years to come. It was just fitting that the actor who, in Lord Desai’s word was ‘Nehru’s hero in the life of India’, had a last shot at mirroring the emerging political landscape on the silver screen before Nehru passed away. In being a light entertainer, and not burdened with profound commentary, Leader also showed how political themes are more likely to find their place in the general mix of mainstream Hindi cinema.

In some ways, the tenor of Hindi cinema’s encounter with the political in the Nehruvian era was similar to the period — optimistic and creative but critically aware of the challenges ahead and the disillusionment creeping in. As the leading site of people’s entertainment of a young republic, it put some bits of key political conversations of the times.

While doing so, it ensured the political animal was enjoyable, in its storytelling and the songs it hummed.