What happens to the ‘illegitimate’ abandoned children of influential people after their adoption by parents out of India? They face an existential crisis

Former cricketer and the contender for the prime minister’s post in Pakistan, Imran Khan, was recently in the news for all the wrong reasons. The autobiography penned by his former wife, Reham Khan, an English citizen and a journalist, has made public certain information that might adversely affect his prospects in the forthcoming Pakistan general elections. Apart from speculating about Imran’s sexuality, Reham’s book has another embarrassing allegation to make — that Imran has at least five ‘illegitimate’ children and some of them are Indian.

It’s not wise to speculate on the nature of such allegations, but a former wife is certainly privy to facts that are out of bounds for others. Children born out of wedlock is not something unheard of in South Asia. Masaba Gupta, daughter of Neena Gupta and Viv Richards, is an example. Neena Gupta was brave enough to acknowledge and give her daughter a good upbringing. But not all are so lucky.

In many cases, children born out of wedlock, especially from the affluent families, are given for adoption out of India. German citizen Arun Dhole, now 45 years of age, is one such adoptee. He had been adopted as a two-month-old by a German couple — Michael and Gertrude Dhole. A few years ago, he met his biological mother after a 17-year of search that included a protracted legal battle. Only after the Supreme Court forced authorities to part with information about his biological mother, he could meet her.

Dhole, who’s in India these days, informs that his adoptive parents were friends of NCP leader Sharad Pawar’s brother, Pratap. It was Pratap who facilitated the adoption. “The power of the family”, he says, was a hurdle and delayed his meeting with his biological mother by years.

So compelling was this quest to find his biological mother and understand what led her to disown him, Dhole is now an activist and works relentlessly to help adoptees connect with their biological parents, not just in India but across the globe. “I am against the trade of children in the name of adoption as it has little to do with child protection. And inter-country adoption, ought to be the last resort for children in need,” says Dhole.

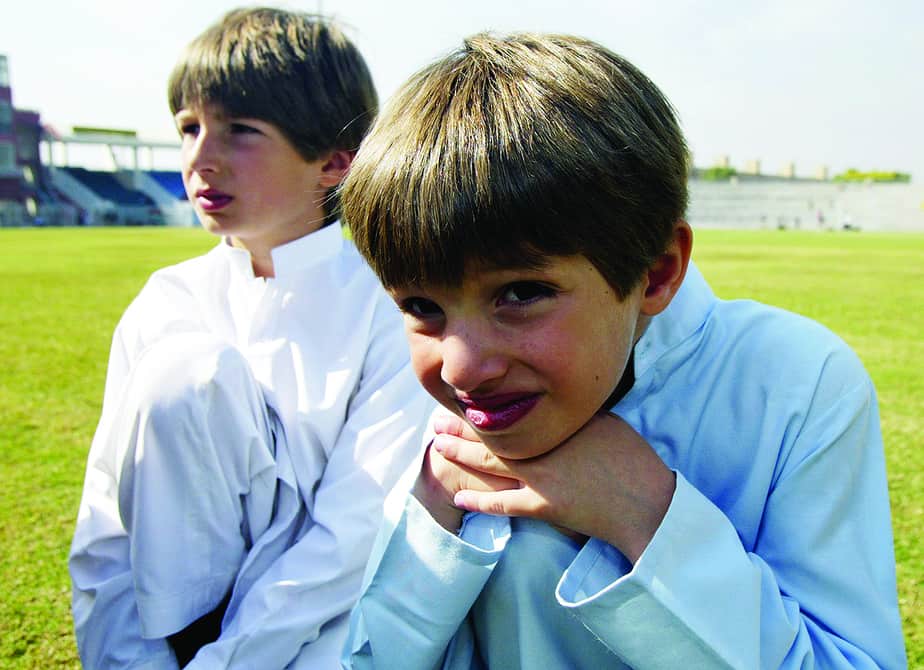

I In the West, an adoptee from Asia is constantly reminded that he or she doesn’t belong there because of the colour of their skin, features, height and mannerisms. Some grow up being ridiculed for looking different.

That’s exactly what this Tamil boy from Pondicherry, Sam (name changed on request), now 35 years of age, felt growing up in Belgium. He was all of eight years when he was given away for adoption by his uncle. After the demise of Sam’s parents, his uncle, who is an influential local politician, didn’t want to share the ancestral property with his nephew. To ensure that, he got Sam kidnapped and arranged for his adoption.

Sam has been staying in Pondicherry since the last few years and likes it there. He has an odd job with a travel agency to support his stay. He hasn’t asserted his claim to his father’s property as he is scared for his life. But it’s not just about losing property —his life got derailed, he lost his mother tongue. Since he’s back, he has learned Tamil but speaks with an accent that makes him stand out among the natives. He even has problems dating local girls, for though he looks like a native, he speaks differently. His struggle is far from over.

Another girl, now 40, claims to be the daughter of a popular politician who died an unnatural death. He fathered her before he was married. Later, she was given away for adoption in India. She was told about her father by a relative before he expired. Since then, she’s been fighting a legal battle for her rights. The matter is sub judice and she wants no publicity at this stage.

Jessica Kamalini Lindher is 36-year-old teacher from Sweden, and last year came to Delhi for the third time in the quest for her biological parents. She might never meet her biological parents, despite her 10-year long search. But last year, when she was in Delhi with her Australian husband and their two children, she met the cop who found her lying on the steps of Sion hospital when she was a 17-month-old. She was later adopted by a Swedish couple in February 1982. Jessica doesn’t want her children to be disconnected from their culture and language, as she felt during her childhood.

Anjali Pawar, an advocate, traced Gaonkar—the cop who found Jessica abandoned. But, unfortunately, Gaonkar had no knowledge of her biological parents even though he did make enquires after finding Jessica abandoned.

So they continue to live tormented lives, always seeking, never quite fitting in. Though they may have had all the creature comforts growing up, a significant piece in the jigsaw puzzle is missing. There’s a sort of disengagement with the adopted country, and the country of birth seems alien. Language is also a formidable barrier. Arun Dhole and Anjali Pawar have helped many adopted children trace their biological parents. It’s tragic, though tearful, that when they meet they hardly can communicate, for they usually speak different languages.

If the allegation about Imran Khan’s children out of wedlock is true, the identity of his Indian children will, in all likelihood, remain a secret. But in some foreign country, they might be grappling with an identity crisis.