On a wintry afternoon at the Capital’s Karnail Singh Stadium around two decades ago, a man nearing 70 stood quietly in the then small pavilion, wearing a worn-out navy-blue blazer and a smile.

Lost in the small crowd of first-class cricketers, Northern Railways officials and journalists, he carried himself as a common man without sulking. It was hard to believe that this was the man who had fans mad enough to force the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) to change the squad and include him in the India Test squad just over three decades before.

But then this was Salim Durani, who had dazzled like a shooting star. He came, burnt bright and faded away. Not for him were any post-retirement plans or managers to maintain his image or finances.

He was hand-to-mouth while he lived, as his teammates and friends tell, and a forgotten man when he died, as they complain.

“He was a fakeer (ascetic) in nature, never attached to anything. Never haughty because of his achievements, nor of wealth whenever it’d come his way,” recalls friend and confidante Anant Vyas, the former Chief Executive Officer of Rajasthan Cricket Association, who first saw Durani in early 1960s as a little kid when the dasher was representing Central Zone against Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) at Jaipur’s Maharajas College ground.

“Such a handsome man, how should I tell you? His collar was always upturned,” says Vyas who shared a close relationship with him through the 80s right until recently.

Durani spent the last years of his life at his relatives’ home where he also died, leaving behind nothing except a legacy of memories, contributions to victories in India’s colours, which he held dearly.

Vyas narrates an incident from a decade ago.

“I thought nobody would be better than Salim Durani as chief guest for the opening ceremony of a T20 tournament we were organising. I requested him and he obliged. We put him up in a hotel and in the evening, I went to fetch him for the function. He came out and sat in the car. He suddenly said, ‘wait, just wait, I have forgotten something very important’. He went back to his room, and when he returned I saw he had the India blazer from 1962 on himself. That blazer had multiple holes, it was in jarjar haalat (poor condition), but he wore it with pride.”

“He was a great man, and a great player in his own right.”

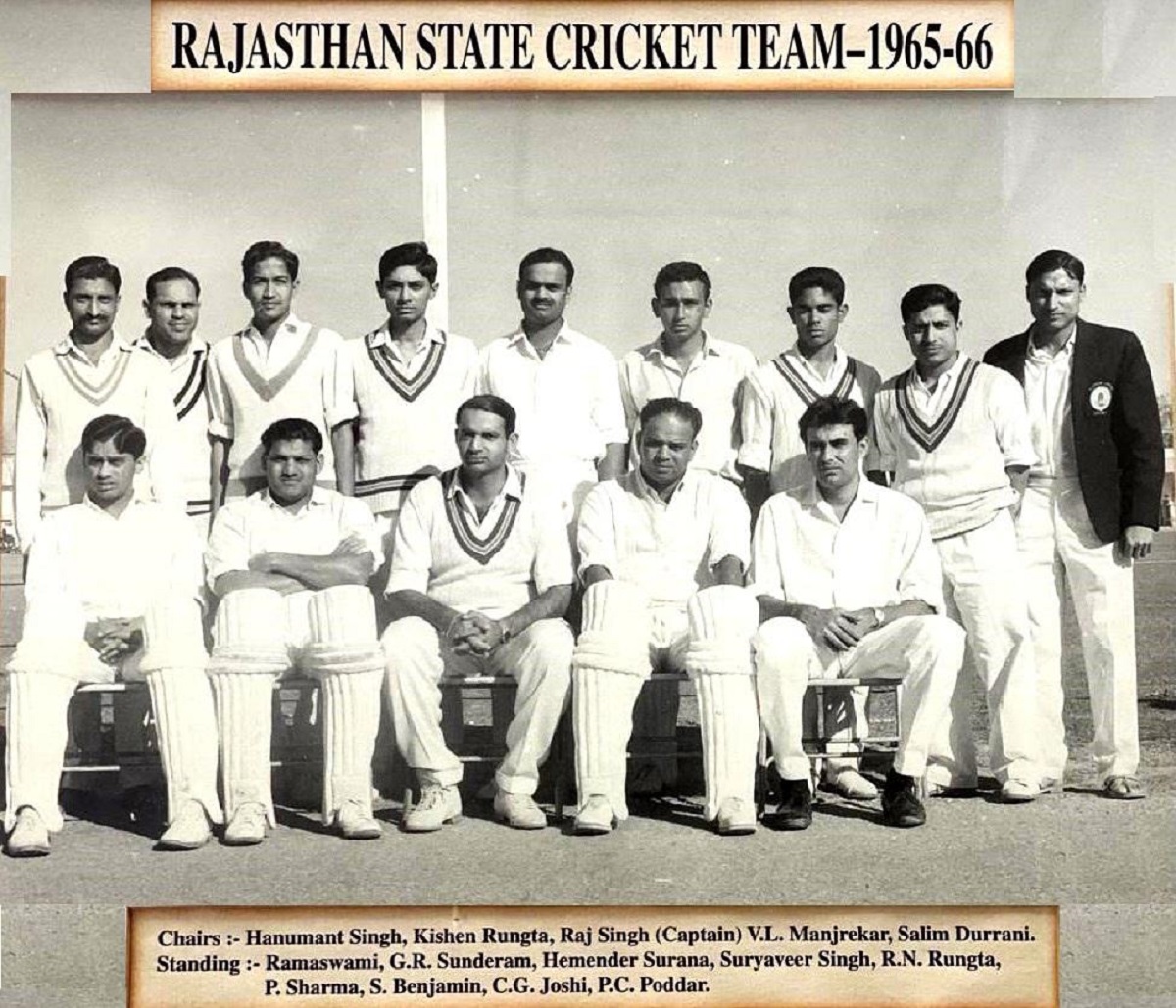

Kailash Gattani, his former teammate in Rajasthan, who played alongside him for seven years through the 1960s and 1970s, sheds light on his stature.

“You see, the crowd had once [during 1972-73 series vs England after he was dropped for fourth Test in Kanpur] protested with a slogan, ‘no Durani, no Test’. This has not happened with any other cricketer, even the greatest. He was loved so much,” says the 76-year-old before explaining why he was loved by the crowd.

“Like in a restaurant, if you order a mutton biryani, you get mutton biryani. With him, you ask for a six, and he would oblige. Basically, you are served what you order. These things are unheard of on a cricket field.”

Although Durani in his chat with this writer a few years ago had made light of his six-hitting legend and attributed it to myth built by fans, his colleagues vouch for it and say that he had a tendency to underplay his achievements out of modesty.

“He was down to earth so will never admit. It is true that if a voice would come from mid-wicket, he would hit a six in that direction and if there would be some call from mid-on, he would hit a six there,” recalled Vyas.

Hemendra Surana, a batsman who played with Durani in the mid-1960s for Rajasthan, too says, “Whenever public would demand, he would hit on that side, he had that calibre.”

Gattani, a pacer who played 109 matches for Rajasthan across 23 years, attributes his popularity with the crowd not just to his dashing playing style but also to his easy-going nature.

“He was a different character. He was a very handsome person and he took to the crowd very easily. He used to mix with them. He never had any airs, was down to earth. He could never speak any language fluently. We used to be roommates for years for Rajasthan and Central Zone and then he used to ask, ‘Kailash, teach me this’. I used to say, “Salimbhai you are the best, you speak in the language you are comfortable. Don’t bother about systematic speech. Just speak the way you feel.”

He was natural and was probably loved for that.

Vinod Mathur, a pace bowling all-rounder who made his Ranji Trophy debut for Rajasthan in 1971 and played for around five years with Durani, recalls the crowd craze for the all-rounder.

“Back in those days, Ranji Trophy matches would sometimes be held in small venues or small grounds in cities, sometimes on matting wickets. We would often wonder why we were playing at places where even 4-5 people wouldn’t turn up for the match. But then a throng would turn up to see Salimbhai,” says the 68-year-old Mathur.

“Once we were playing at the Railways ground in Jaipur. All the coolies turned up to watch Salimbhai bat. When he was not in action, they would return to work but come back again waiting to see Salimbhai bat again. He was extremely popular.”

Sanjay Vyas, another Rajasthan ex-cricketer, who had seen him play but could not share the field with him as he was very junior says there was something that made him stand out.

“He had an aura, a personality which was different from all other cricketers. I have never seen any of it in even any other international cricketer. His cricketing knowledge was exceptional and his reading of players was sharp. A player would play 3-4 balls, and Salimbhai would tell us about his weakness or strength. He was a good reader of the game.”

It was probably that ability to read the game that made him win the key moments.

Like in 1971, he demanded the ball from skipper Ajit Wadekar and took two key wickets of Clive Lloyd and Sir Garry Sobers in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, to rock a recovering West Indies from where they lost track and lost the match to hand India their first Test win in the Caribbean. Or earlier in the 1960s, he would ask the ball from the then captain MAK Pataudi to inflict similar double whammies to stall cruising oppositions like New Zealand and West Indies although the eventual results wouldn’t fall India’s way.

Mathur recalls an incident from Jamshedpur where they all had gone once to play Russi Modi Gold Cup as part of Rungta XI in the early 1970s.

“Dilip Sardesai was the captain of Rungta XI which also had Vijay Manjrekar and Salim Durani. We had these three seniors while the rest of us were Rajasthan youngsters. It was a big tournament. Tata XI, Mafatlal XI and Nilon’s XI had also come. There was also a team from Bengal.”

Laxman Singh and Najmul Hussain opened the batting for Rungta XI.

“Anjan Bhattacharya, a medium fast bowler from Bengal, hit Najmul Hussain on the head with a bouncer. Hussain fell down and had to retire. We were sitting in the pavilion — Hanumant Singh, Dilip [Sardesai], Vijay [Manjrekar]. We saw Salimbhai, who was supposed to bat at No. 5 or 6 walk into the field. Sardesai fumed and said, ‘why is Saleem going in to bat at No. 3. Stop him’. Manjrekar held his hand, and said, ‘let him go, don’t stop him. He is in mood’. The way Salimbhai batted that day, it was worth watching. He would be peppered with bouncers but he’d take them on. He made 80-odd runs. He changed the course of that 50-over match. The way he batted, Manjrekar said, ‘See, this is Salim’,” recalls Mathur.

“It was his confidence that was different. He was a born cricketer, no doubt, but it was the tremendous confidence he had in his abilities that marked him out.”

Gattani recalls a game between Central Zone and MCC. He hit both off-spinner Pat Pocock and left-arm spinner Norman Gifford over the boundary.

“When a British correspondent asked him how could he hit turning deliveries, especially from off-spinner to mid-wicket, Salimbhai asked me to tell the correspondent, ‘he (Pocock) doesn’t know how to turn. It is coming out straight. If they want to learn to spin, come to me’. He didn’t care a damn for names. And that is one of the great things I learnt from him, see the ball, not the bowler.”

Surana says that he was perfect fit for the T20 format.

“Unfortunately, we didn’t play limited overs as much back then. He would have been a hit, nowadays.”

Sharad Joshi, who made his debut as a 17-year-old with Durani in the side and was encouraged a lot by the ‘soft-spoken and polite’ man, concurs, “I feel if IPL was there during those times or if Salimbhai was born in this era, he would have been the costliest player.”

Joshi says that the most remarkable thing about Durani was the way he befriended youngsters. “I called him sir but he chided me and said, ‘what is sir, call me Salimbhai.”

Sanjay Vyas says, “Unfortunately, I could not play with him. But his guidance was always there. He was so soft-spoken. He gave us a lot of tips. He told us to stay disciplined and would tell us, ‘Son I have done so many things, you don’t do that. Focus on your game’.

There are tales of his colourful life.

But as Gattani points out, “That man was remarkable. You can’t believe, he could drink till 10, 11 ‘o’ clock, sometimes 1.30 and next day he would be absolutely perfect for the game. No problem.”

But what made him exceptional as cricketer?

“He had a high-arm action, his height was over six feet. His quality was that when he would spin the ball, you could hear the sound of the spin due to the number of revolutions he would impart. The high-arm action would give him extra bounce. He used to turn the ball a lot. From Bombay, Bapu Nadkarni was there. He was very good at spot bowling but Durani used to turn the ball,” says Surana.

“He was good enough like any of today’s players in terms of technique. But the difference was, he played only 4 or 5-day matches. Nowadays, if he were there, there would be no match for him.”

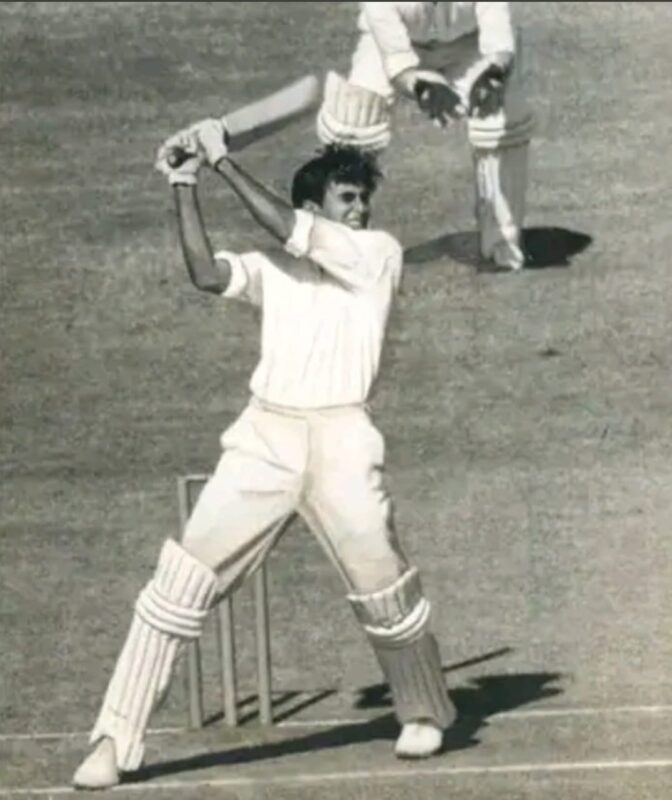

With the bat, he was dashing and Surana says that he had plenty of time at hand.

“When he played fast bowlers like [Wesley] Hall, [Charlie] Griffith and [Chester] Watson of West Indies – who would bowl very quick – he seemed to have enough time to play them.”

“Left-arm all-rounder like Garfield Sobers was a far bigger name than him but he was no less.”

Although not fond of running on the field and dirtying his clothes and always fielding in close-in positions, he never dropped a catch, adds Surana.

Gattani says that he had variety in his bowling.

“He could bowl the normal spin, he could also bowl from back of the fingers – both orthodox and left-arm wrist spin. He had a huge palm. He looked ungainly because of his long strides. But never dropped any catch off my bowling.”

Joshi also talks about the edge that the extra height gave him as well as the turn thanks to his big hands.

“He was six feet tall. He imparted a lot of spin and extracted a lot of bounce. It was very difficult to hit him. As a batsman, he could hit all across the ground. He was a very good stroke-player.

“His drives and cuts were good. But he reserved special treatment for left-arm spinners. Because he was a left-hander, he used to relish left-arm spinners and leg-spinners. Used to get very attacking.”

Sanjay Vyas adds to it, “He used to turn even on flat wickets. He had such solid, big fingers. We don’t see those kind of turners nowadays. They all are finger spinners. They don’t turn on pata (flat) wicket. But those who use wrist, they can turn. He would impart wrist even in left-arm orthodox. The kind of wrist and finger coordination he would have, because of that he would turn and bounce the ball thanks to his height.”

He also calls him a ‘brainy cricketer’ who knew, “what kind of bowling is needed on a certain wicket, what to bowl to a certain batsman”.

He was particularly severe on left-am spinners because, as Gattani says, “he used to consider them as his competitors. He wouldn’t respect even the likes of Padmakar Shivalkar”.

“Once we were playing for Central Zone against South Zone in Duleep Trophy. We were seven down and needed 80 runs. He hit a couple of sixes off left-arm spin and I told him, ‘Don’t hit now. We have no wickets. He said, ‘they all are lesser people’.”

Those who knew him say Durani was large-hearted.

Not only was he generous with youngsters as Joshi points out, ‘he was very gentle to youngsters’, he was always willing to spend on his friends whatever he got.

Says Surana, “He was patronised by Udaipur, His Highness [Bhagwat Singh Mewar]. He was financially weak. But whatever money he got, he’d spend whole-heartedly.

“The ruler would tell him something like, ‘Salim, if you make a hundred, you will get Rs 5,000’. That was a lot of money in those times. He would score. When he would get that Rs 5,000, he would enjoy it with all the friends. This was despite the fact that he was financially hand-to-mouth.”

The all-rounder played 29 Tests, scoring 1202 runs and picked 75 wickets. He also played 170 first-class games, hitting 8545 runs and taking 484 scalps.

The international figures may not merit him a place in the list of all-time India XI but as Tiger Pataudi once famously said when asked about picking an all-time India XI by Amrit Mathur, a former India team manager: “Put anyone’s name, but make sure Salim is in it”.

“The idea was that eight or nine players would naturally select themselves but Tiger thought Durani needed to be on that list,” says Mathur.

Or as Gattani says, “Such people are God-send men, you can’t copy them, you can’t imitate them, they are born once-in-a-lifetime. He was one of the greatest. I feel proud that I played cricket with him.”