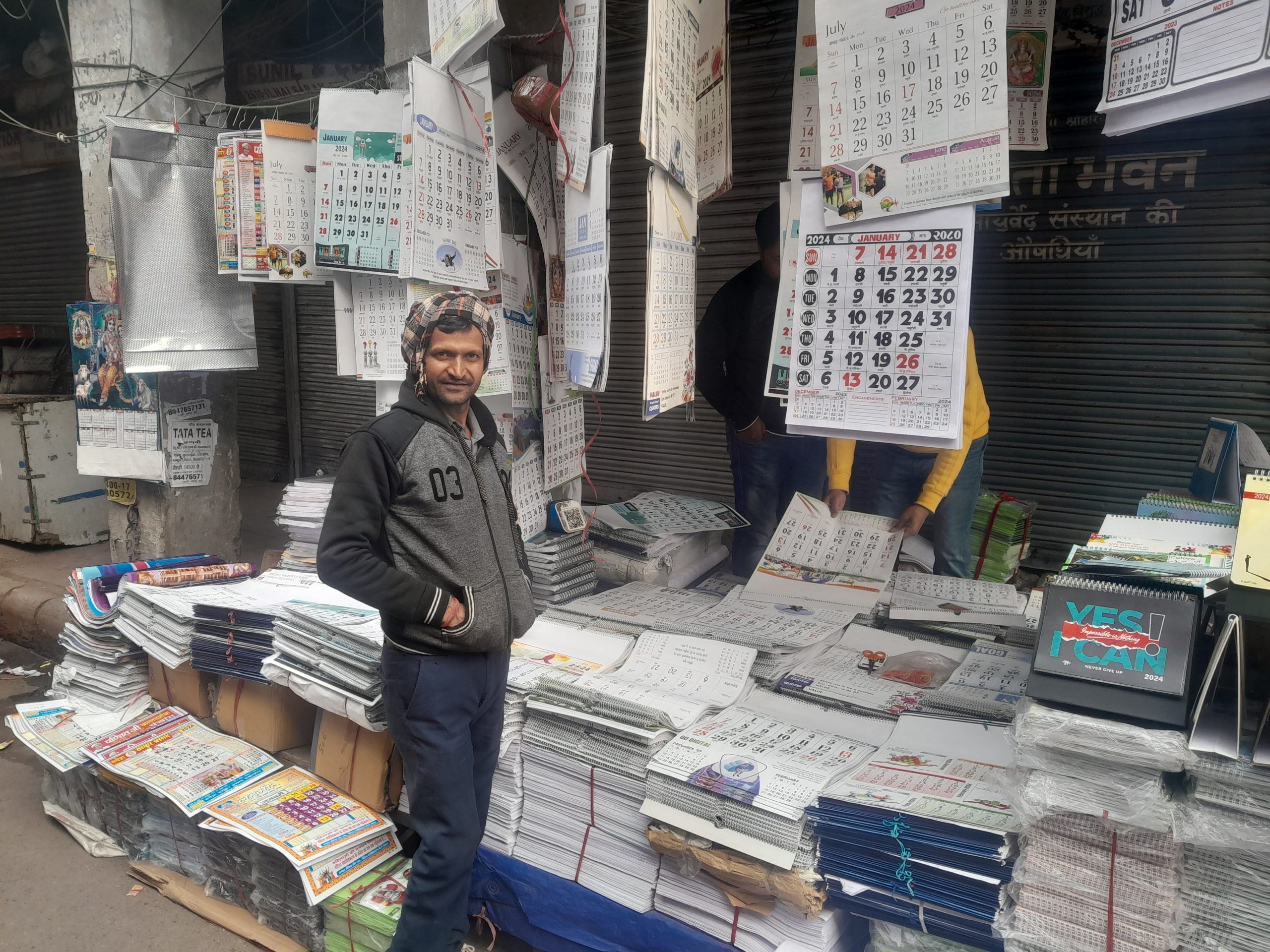

On one of the coldest afternoons during the first week of the New Year in the national capital, Devinder found himself waiting for customers in his calendar shop on the road in Old Delhi’s Nai Sarak. After a while, a customer approached and, after some bargaining, purchased six calendars.

“The demand for calendars exists, but sales have dropped compared to earlier years,” he shared with Patriot.

Devinder, a native of Uttar Pradesh, has been selling calendars every year for about a month during the New Year in Nai Sarak, known as the home of the country’s biggest and oldest calendar market.

“After COVID, the price of calendars dropped, but it has now soared again,” he added.

In the old days, calendars held high importance in human life as the primary source of dates. In today’s digital age, however, the significance and sales of calendars have suffered a massive drop, worsened during the pandemic and struggling to recover through format changes and modernisation.

“In the past, there was a craze for hanging calendars in houses. People adorned their walls with calendars, a trend that has dwindled,” Rajiv Gupta, a 59-year-old manufacturer and wholesale dealer of calendars in Nai Sarak, explained to Patriot.

Gupta, one of the oldest dealers in Nai Sarak, operates ARG Calendars Private Limited. This shop, established by his father around a century ago in Delhi (then Indraprastha and British India), has witnessed the gradual decline of calendars becoming fashionable in big cities.

“Wall calendars have dropped due to home interior design; there’s no space left on walls,” Gupta further observed.

Despite calendars falling out of fashion in big cities, Gupta supplies calendars not only in India but globally, including to Mauritius, the West Indies, among other places. He does not attribute the decline to digitalisation.

“This is not the result of mobiles and digitalisation but rather a change in trend. In rural and small cities, calendars are still in demand. Additionally, people (NRIs) like to carry calendars abroad because they can’t find them there,” Gupta confidently stated.

“Digitalisation is not a substitute for calendars. It cannot be.”

In the thick of political campaigns

Regarding the use of calendars in political campaigns, Gupta, busy in his office, disclosed that politicians are utilising calendars for their campaigns in present times. He pointed out a wall calendar with the pictures of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“This is an election year. Politicians have ordered in crores, and I’ve received orders in crores. Calendars have become a source of campaign now. People might tear or throw away election pamphlets, but they hang politicians’ calendars for a year,” he noted.

Gupta, an MBA and LLB, reluctantly agreed that the calendar business would not see growth in the future.

“It will not increase. People no longer appreciate calendars even as gift items but have shifted to more expensive gifts. We have also expanded to include wedding cards, among other things.”

When asked if he would pass on the business to his child, as his ancestors did, Gupta instantly replied, “No! I can give it, but I haven’t thought about it yet.”

Nai Sarak is also one of India’s biggest textbook markets, established in the 17th century near the historic Jama Masjid.

Aman Thukral, 44, is busy managing diaries and other items in his shop.

“The trend of calendars has changed. People now prefer to distribute fewer but higher quality calendars. The materials used in decoration have also changed,” Aman said.

Aman, running ‘Rana Calendar,’ supplies calendars globally, including to Netherlands and Pakistan. His shop was set up before partition by his grandfather. He disagreed with the idea that digitalisation has negatively impacted calendars.

“There is no effect of digitalisation. People who want to see a calendar will see it. Today’s calendar is the main source of publicity and campaign. (Only the trend has changed),” Aman emphasised.

While other calendar manufacturers and dealers at Nai Sarak acknowledge that sales of paper calendars have suffered, Risabh Aggarwal, extending his ancestors’ Dharamsen Enduring shop in the market, attributed the decline to digitalisation, COVID, and government policies such as GST.

“This shop was set up by my ancestors in 1917 before the independence of India after coming from Lahore, Pakistan. Although people still look at calendars, business has dropped by around 50%. Those who used to order 2000 pieces now order only 500,” Risabh noted.