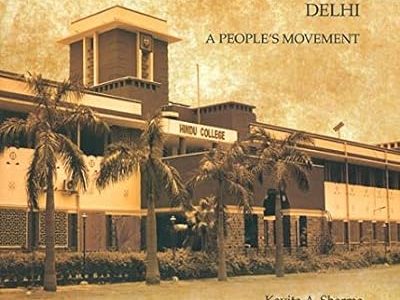

The history of Delhi University’s celebrated Hindu College, which began as a breaking ground for anti-British feelings in 1899, has been comprehensively captured in the book A People’s Movement, written by Kavita A Sharma and WD Mathur.

The book, published in 2014, came into limelight again at the 125th foundation celebration of the college last week in the presence of Jagdeep Dhankhar, the Vice President of India, as well as college’s alumni including Bollywood stars like Imtiaz Ali, Rekha Bhardwaj, Vishal Bhardwaj, Tisca Chopra, Prateek Srivastav, and Aishwarya Sakhuja.

The authors have chronicled the history of the college through painstaking research following visits to libraries — Teen Murti House, Hardayal (Harding) Library, Marwari Library, Delhi Public Library, Central Secretariat Library, and India International Centre. Visits were paid to homes of the survivors of the main characters involved for information and photographs.

Kavita A Sharma, an academician and the first woman Principal of Hindu College and second college student to become its Principal in 1988, shares an interesting anecdote in her Preface to the book.

She mentions how in 1974, Bharat Ram, the then Chairman of the Governing Body, said, “I would like to suggest to Dr. Bhatia (then Principal) that he should commission some knowledgeable person to write the history of the College which is 75 years old. While we would not like to say anything about this knowledgeable person, it took almost four decades before we could gather the courage to take up this stupendous work.”

Exactly 25 years ago, the then Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee was personally present to celebrate 100 years of the College on its Founder’s Day on February 17, 1999.

A commemorative stamp issued by the P&T Department on that day, reads, “Hindu College was a centre for intellectual debate during India’s freedom struggle, especially during the Quit India Movement. In fact, the college remained closed for several months in 1942, responding to Gandhi’s call to students and teachers to join the Movement. Its amphitheater at Kashmere Gate provided a stage for scintillating speeches by famous leaders like Lokmanya Tilak, Annie Besant, Mahatma Gandhi, Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya, Sarojni Naidu, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Motilal Nehru, Jawaharlal Nehru and so many others.”

The fact that the College came out of a people’s movement is evident from the story of its evolution as a means to create a secular and informed generation of students even though it began with a motive to promote Sanatana Dharma as Hindus felt threatened by the Christian missionaries who came in the guise of educationists.

The establishment of the Mission (St. Stephen’s) College in 1881 acted as a spur to the worried Hindu nationalist thinkers and in 1899, Hindu College came to represent the nationalist movement and breaking ground for anti-British feelings.

An RTI response about the college says, “This college was established in May 1899 for the purpose of giving cheap but efficient secular education with sound religious instructions according to the principles of Sanatana Dharma.”

The credentials of the founders of the college mainly Lala Shri Krishna Das Gurwala should provide sufficient reason for the foundation of Hindu College. After the revolt of 1857, Seth Ramji Das, grandfather of Lala Shri Krishna Das, was brutally killed by the British in Chandni Chowk because he refused to pay them but had helped Bahadur Shah Zafar the last Mughal emperor in reorganising his army.

The book chronicles its journey from Kinari Bazar to Kashmere Gate and finally to its present location in the North Campus and the role of various businessmen, educationists and others who helped in this journey.

The spirit of questioning and defiance was ingrained among its staff and students.

One of the points of contention today is whether the police have the authority to enter a college.

The book mentions an incident of the Quit India Movement in 1942, when students who had taken out a procession on the call of Mahatma Gandhi were chased by the police till the college gates. When they had entered the college, the Principal stood at the gates and told the police they could go back, which they did.

This confidence was reflected among the students as well.

JN Kapur, an ex-Hinduite mentions that a large procession was gathering near the gates of the Hindu College at Kashmere Gate.

A group of six British soldiers aiming their guns came up to him and asked him what was he doing. He simply told them, “I am in my college and you cannot enter here without the Principal’s permission.”

They stared at him and went away.

The fascinating section on the freedom movement mentions a list of students from Hindu, Ramjas College and Indraprastha College for women (the then only women’s college in Delhi) who were arrested for participating in the call of Mahatma Gandhi.

But there was no hard and fast rule about violence or non-violence. The common aim was to throw out the British and not surprisingly some chemistry students were also trying to prepare bombs to scare the British. That it could not be carried out is a different story.

The book also mentions the resistance from the higher authorities like the Principals, who were ordered to rusticate the guilty students or their grants would be stopped.

Among the various activities that Hindu College could be proud of was the setting up of the Harijan Service League in 1932.

Actively aided by GD Birla, it supported mass education, improving the condition of slums and fighting caste practices.

The students got a chance to listen to leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Annie Besant, Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, Madan Mohan Malviya, Sarojini Naidu, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, Jai Prakash Narayan, BR Ambedkar among others which shaped their thinking and actions.

The college also offered shelter to Chandrashekhar Azad in the hostel and welcomed Mahatma Gandhi, offering him Rs 500 which meant a lot in those days.

But revolution comes with a package.

It may come as a surprise that a Principal like NV Thadani who stood outside St. Stephen’s (arch-rival) to stop rioters from attacking it could not tolerate boys and girls even within talking distance in a college that prides itself for allowing admission to girls in the 1930s.

Girls were asked to sit on the front rows and had to enter from the front door. The library was out of bounds. The college staged a play every year where boys played the role of girls.

But then Kapila (Vatsyayan) Malik, doing her English honours, insisted on girls joining the dramatic society. She was one of the dozen girls in a college which had 1,000 boys.

Among her contemporaries was Sheila Bahadur who went on to become a classical singer. She started taking part in the Debating and Literary Union. Married to Prof. PN Dhar, she was the chief editor of NCERT as also the Director of Bal Bhawan. But that was only the beginning of the journey for women who found space to spread their wings through their vigour and conviction.

The narrative of the book and its style divided into chapters like ‘Roots of Nationalism’, ‘Creation and Evolution of Democratic Spaces’, and ‘From the Mists of Time’ makes it clear that it is no ordinary narration but a history of India’s freedom struggle intertwined with the evolution of its intelligentsia.

‘Our universities lack basic academic infrastructure’

Kavita Sharma, the first woman Principal of Hindu College and former director of India International Centre (IIC), has taught in India and abroad for 37 years including at Hindu College, Tokyo Woman’s Christian University and Universitas Indonesia. A Fulbright scholar and winner of the Indira Gandhi Sadbhavana Award in 2005, she has authored several books before this one. She spoke to Patriot on the book and other matters like National Education Policy.

What was the most exhilarating part of writing this book?

This is a book that I wanted very much to write. In Bobby (WD) Mathur, I found an able collaborator. He belongs to that area (old Delhi) and knows Chandni Chowk, Dariba among other places. He is a Hinduite and has been a good journalist. As we got into it, the most exhilarating part of it was unearthing layers of the past. We tried to trace the first place from where Hindu started. I lodged an RTI to get the names of the original board members and then started figuring out who they were and why did they join hands in this enterprise. I realised that they covered a big spectrum of ideology but yet were united. Had to do a lot of background reading to figure out the education status at that time in Delhi. The Chief Librarian of IIC rendered sterling service by also looking for archival material and mention of Hindu College in rare book collections.

And the most difficult part?

To meet old students was difficult and Bobby helped in that as also in going through archives. He and I also roamed the lanes and bylanes of the area and learned a lot about Shahjahanabad and our heritage. Some old students came too. Getting photographs was also difficult. Rajkumar Oberoi, a former Prime Minister of the College and BD Saini also helped with books and pictures. The magazine Indraprastha was a mine of information.

On the rivalry between Hindu and St. Stephen’s (college across the road)

The rivalry between Hindu and St. Stephen’s was also because of our different visions and aims. Also St. Stephen’s had establishment support while we were a rebel college. This was particularly evident in sports. When I was a student, you had to go to the ground when Hindu and Stephen’s played cricket finals. But there was also collaboration as we allowed St. Stephen’s students to use our bio-science labs as they had only physics and chemistry. Besides, Hindu, Stephen’s and Ramjas collaborated in establishing Delhi University.

Being aware of education systems of many countries, how do you rate the Indian education system?

Indian education system has far to go to catch up. We cannot live only on the glory of the IITs and IIMs and institutions like Indian Institute of Science. The bulk of education takes place in the state universities, almost 88 per cent and they are in bad shape. And even the central universities have too much bureaucratic interference either from UGC or MHRD (Ministry of Human Resource and Development). There are fault-lines of caste, creed among others.

Why do our universities fare so badly in world rankings?

Our universities lack basic academic infrastructure. Research is lacking. Pedagogy is outdated and syllabus and curriculum are not regularly updated. Also, world rankings are heavily weighted in favour of the West although now they have also started Asian rankings. But to be counted in global education, we must make a place for ourselves there as Singapore and China.

What do you think of the National Education Policy?

The very ambitious NEP is a very good policy but its implementation will be a Herculean task. I am doing an initial pilot in unitary central universities and, if it succeeds there would be a climate for better implementation. However, the difficulties because of lack of basic infrastructure and physical infrastructure would be hard to overcome.