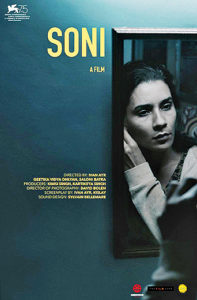

Netflix release Soni is an honest take on a woman in a position of power struggling to find space in a man’s world

Which Indian woman hasn’t heard of the familiar trick of applying sindoor (vermilion) in the parting of our hair as an acceptable measure to ward of sexual harassment?

After the December 16 rape case, much of the conversation about women’s safety moved to that of self-defence. Learn karate, carry pepper spray, download that app—because men will not change. Male outrage about the recent Gillette ad is further testimony to the fact that men are blissfully unaware of the oppressive world that women exist in, which is a direct result of male aggression and privilege.

After the December 16 rape case, much of the conversation about women’s safety moved to that of self-defence. Learn karate, carry pepper spray, download that app—because men will not change. Male outrage about the recent Gillette ad is further testimony to the fact that men are blissfully unaware of the oppressive world that women exist in, which is a direct result of male aggression and privilege.

Soni, released on Netflix on January 18 and directed by debutant Ivan Ayr, is one of those rare films that tells the story of women in positions of power who struggle to find space in a man’s world. While the film itself is loose in terms of direction, dialogues, acting, and editing, it tells an important story that needs to be heard.

Soni could be described as a cop film—Geetika Vidya Ohlyan plays the titular Soni who is a police officer—but with no exploding cars, action sequences, or chase scenes. Juxtapose that with the recent superhit, Simmba, which tells the oldest story of female rape and male revenge, where even the songs are recycled. Granted, people watch a Rohit Shetty film for the explosions, gravity-defying stunts, and lowbrow humour, but that only prompts one to wonder if toxic masculinity will forever remain the all-season flavour. It is possible to sit through Simmba and forget that a girl gets raped and murdered. The story is about Simmba atoning for his sins to become a better human being, while being validated and adored by all the women in his life.

The ultimate male fantasy, it seems.

Simmba smashes up the bad guys, the audience applauds. But Soni’s world is different. Soni beats up a molester and her seniors pull her up for not following due process. “Sindoor laga le (apply vermillion),” her neighbour offers as a precautionary measure to keep rowdies at bay. Simmba catches influential people running a drug racket, he beats them up, and gets suspended. Soni retaliates when a drunk army officer and, later, a politician’s son snorting cocaine in the women’s toilet of a restaurant misbehave with her and gets transferred to the police control room where she won’t make so much trouble.

Both Simmba and Soni are reprimanded for their actions, but while Simmba’s team wholeheartedly supports him to cheat the system for justice, Soni is forced to toe the line and lie low. In the pack of women who adore Simmba is his love interest, Shagun, who conveniently runs a catering service, feeds him on demand, and stands by his legal and illegal methods of dealing with criminals.

Here again, Soni’s world is different. Soni is told to cap her anger and not take the law into her own hands. Her supervisor, Kalpana, is chastised by her husband, also a cop, for being too soft on her team, while he points out to her that no junior in his team has dared to get out of hand under his watch.

Simmba and Soni repeatedly remind us that in cinema and real life, the boundaries for expressing anger and aggression and for breaking rules are infinitely different for men and women. One’s actions are applauded, while the other’s is penalised.

Compare Soni with the 2016 Malayalam comedy Action Hero Biju, which follows the many trials and tribulations of sub-inspector Biju Poulouse in a Kochi police station. Each day is a new case that Biju has to navigate, but his authority as a man in uniform is never questioned. He never has to worry about being felt up; isn’t paraded as a decoy to nab anti-social elements; isn’t “complimented” on his voice and body while trying to arrest someone; isn’t brushed off for his gender; doesn’t have to answer to his fiancé and family for his demanding job. Biju, like Simmba, is a star and a loved protector of the people who deserves salutes and the country’s respect.

Soni’s life is not as simple.

The vastly dissimilar worlds that Simmba, Action Hero Biju, and Soni capture mark the realities of male and female authority and power. Soni lays bare the fact that a woman with power, even one in uniform, cannot shrug off her identity of being a woman. Both Soni and Kalpana grapple with issues at home, where they are expected to be wives, mothers, and sisters first. Their cop-ness doesn’t for a moment allow them to step away from their woman-ness.

Soni is a stark reminder that even in positions of power women are dished out the inevitable role of being the caretaker, placed strategically for when intervention from a woman cop is needed, while men take decisions on when and where that will be. A problem the Simmbas and Bijus of this world do not have to deal with.

If Simmba and Action Hero Biju are cop films, perhaps Soni is not a cop film then. The fact is no matter what the reality might be, in mainstream films, cops are fearless justice seekers with a free hand to crush anyone in their way. Soni is fearless, is an honest justice seeker, and wants the same authority that male cops have to get her job done.

She ticks all the boxes, but she is a woman first and so there are more checkboxes for her to fill.

www.newslaundry.com