The festival wants to redefine the word ‘Dalit’ to include other oppressed communities

Sanvidhaan aisa likh diya … sanvidhaan likh diya, sabka haqq barabar kiya, ban gaye lukman Hakeem, Daliton ke prann bachaye ji teri, jai ho baba bheem … oh bheem, tane Dalit upar uthaye ji … Aise bole the London mein, jaise sher dahade thavan mein, bhai aise waha speech, angrez sabh dehraye ji teri.

Standing on a podium in the open air ground of Kirori Mal College of Delhi University, 15-year-old Trishla Boddh recites a poem written by her father. “I’ve been reading my father’s poetry since the age of seven,” she says. “I understand Babasaheb’s (BR Ambedkar) mission through the words of poetry which my father wrote. And I learn a lot from it.”

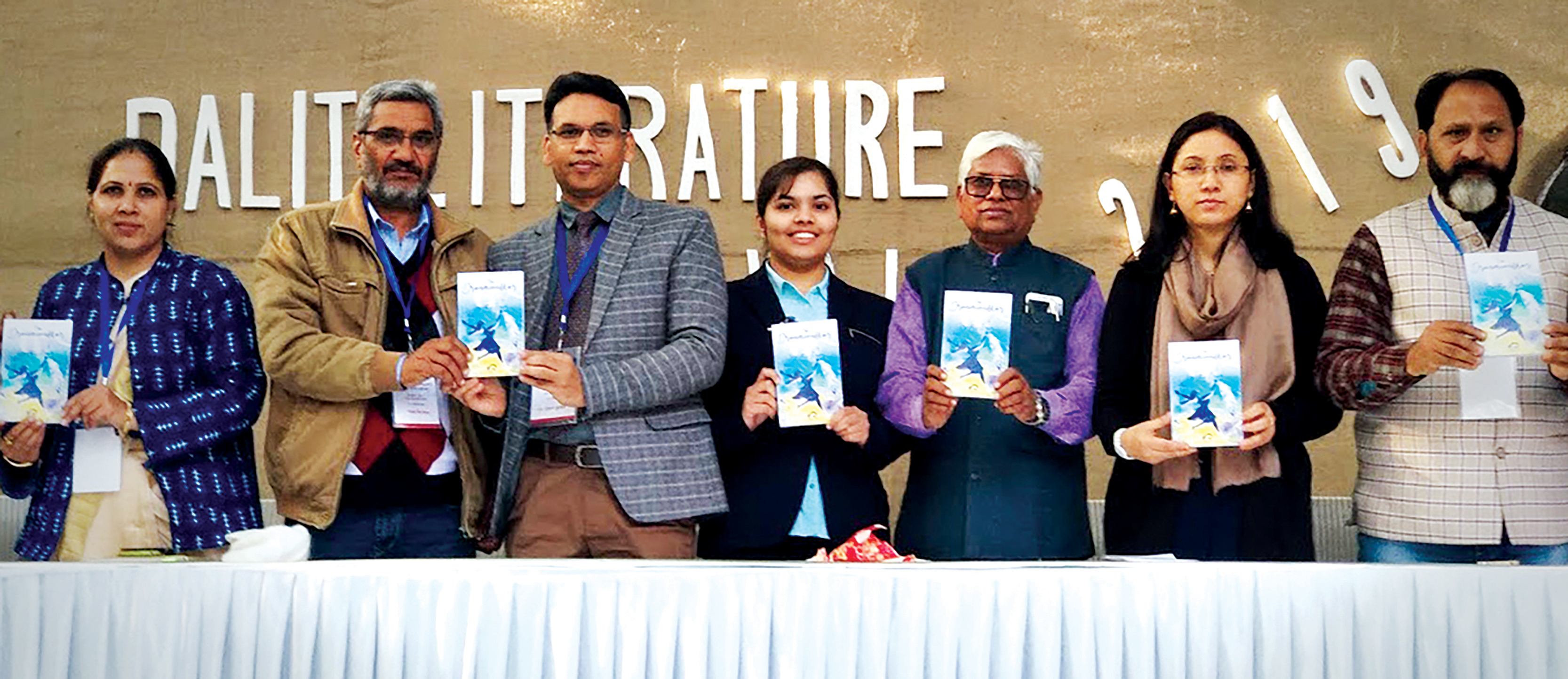

Boddh was one of several speakers at the Dalit Literature Festival in Delhi on February 3-4. The festival was organised by Ambedkarvadi Lekhak Sangh, KMC’s Hindi department, Rashmi Prakashan Lucknow, Ridam Patrika, National Alliance for People’s Movements and Delhi Solidarity Group. The festival’s motto was to “bring together various cultural and artistic minds who believe in social change and justice, to strengthen the people-oriented and change-centric positive stream of Dalits”.

Suraj Badtiya, a writer and founder-member of the festival, says, “In the name of literature, several festivals are happening around the country. They want to make literature a source of entertainment. It is not. It makes us human. It gives us the power to see a better society by first changing us from within.” He adds, “Of course, they will leverage upon the entertainment value of it. So they continue to sell it. Literature is not a joke that it is meant to entertain you.”

Badtiya says society is already divided on the lines of caste, and this festival does not divide it further. “If the same castes come together to show their pain through their writing, then there’s absolutely nothing wrong with it.” He says the purpose of the festival is also to redefine the word “Dalit.” He says the word will now include “oppressed communities like adivasis, farmers, labourers, denotified tribes, women and the transgender community”.

Talking about the importance of nomenclature, he says: “Jis shabd se hum jhelte hain. Wohi shabd hamari taakat ban jaata hain (The words that make us suffer, end up being our greatest strength).”

Badtiya adds: “We had no funds. We kept a donation box to raise funds, and we are putting everything in the records. Had we collected funds from outside entities, we would’ve had to follow their instructions and agenda.” According to two sources from the organising committee, the festival raised Rs 3.5 lakh worth of funds. This consist of donations from teachers, students and the organising committee members.

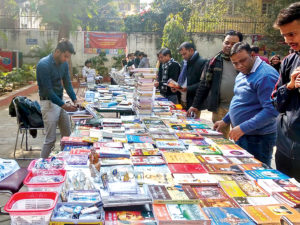

The open-air ground also has stalls of lesser-known book publishers, their booths filled with books. Topics included the struggle of Dalit women, Marxism, societal issues and solutions, the politics of Dalit literature, autobiographies and poetry.

Sanjay Kumar, a student from JNU attending the festival, says, “Dalit literature consists of many realities which we don’t hear. Through their autobiographies, Dalit authors share their struggle. That’s the essence of the Dalit Literature Festival.” He says once the festival becomes more popular and people hear about it, it will “challenge the canon form”. In the context of the prevalent Brahminical mindset in society today, Kumar adds, “Through this festival and Dalit literature which is being offered here, you can challenge the unequal practices in the society.”

Another visitor has come from Jaipur, where he also attended the attends Jaipur Literature Festival. He says, “In a place like Delhi University which is controlled by the upper castes, they’re holding a Dalit literature festival— it’s a positive sign for our social empowerment. It thrusts the movement of Babasaheb, sidelined sections of the society are being heard now.” Talking about Dalit literacy rates, he says, “India was envisaged as a welfare state. It means education is a centrally sponsored subject. After 1991, they have deviated from that welfare state concept. It’s still in the Constitution, but we’re a capitalist country now.”

Just before the afternoon session commences, a stream of people come from the Kirori Mal College canteen, taking their seats and exploring the bookstalls. One of them is Manik, a research scholar from Chittorgarh, Rajasthan. He talks about the personal inhibitions Dalits face on a regular basis. “Some of them feel not to speak about personal struggle and identity in the public domain. They should write about it. They don’t have to write everything, but their struggle is important and it helps the movement also. People first thought that Dalit literature cannot only consist of autobiographies but prose and poetry too. It’s coming out slowly. There’s not a single paper of Bahujan Samaj with nationwide circulation. Work should be done on this too.” said Manik.

Manik says discrimination also exists within Dalit sub-castes. “A person from one sub-caste will not go out with a person from another sub-caste. They don’t eat together. So, discrimination exists within them also. They will have to work together.”

Also speaking at the festival is Laksham Gaikwad, a writer from Maharashtra. Gaikwad talks about the Vimukt Ghumantu caste who were called “criminals by birth” and had been jailed by the British for 80 days. In 1952, he says, “We were given freedom but we were slaves even after Independence. The situation is such that in this country, a budget is there for the animals, but there’s no budget for adivasis from Vimukt Ghumantu caste. Why?”

Gaikwad says: “Maine pucha Hindu dharm mein sudhaar kyu nahi laate?. Brahmin ne gau sambhali toh woh sabki maata ho gayi, Vishnu ka avtaar ghadha hum sambhale aur uske liye gali hoti hain, fir usko baap kyu nahi banate? Gadhe ko bhi baap banao na.”

With elections around the corner, he says if tomorrow, good work is done by the BJP or the Congress, it will still be welcomed. “Agar Hindu dharm ko aage jaana hain, samanta banani hain, toh Bhagwan ke haath ke hathiyaar bhi nikal do aur aapke bhi ghar ke hathiyaar phek do. Desh azaad hain. Manavta ki tarf chalo.”

Ved Prakash, a YouTube activist with over 3.5 lakh subscribers, is sitting in the audience. He says there are many politicians trying to weaken their fight. “They join hands with the Manuvadi power to make us weak. Our fight is against two people: the backstabbers and the Manuvadi forces.” Prakash is disappointed in the vibe of the festival. “The people who are standing here have no energy. They don’t give chance to the youth, just like Mayawati doesn’t give a chance to youth in politics. I thought since the festival is happening in Delhi University, the youth will flock in huge numbers. But, sadly, that’s not the case.”

Organising committee member Sanjeev Kumar Danda of the Delhi Solidarity Group says the festival will definitely be continued. “We just have to think the level on which it will be organised in the future. I think the infrastructure this time was very basic. The per day cost of the festival is Rs 1.25 lakh which includes mic systems, sound and food. We have a donation box and were able to raise approximately Rs 25,000. Not only did many authors come as speakers to this festival, and they bore their expenses themselves also. So we will definitely continue this.”