The celebrated Bengali poet, Jasimuddin, invites a friend in one of his poems, ‘Nimontron’, to enjoy the beauties of the natural landscape of his village filled with abundant greenery and a river flowing by its side. Through his poem, he depicts the nature of rural Bengal — abound with flora and fauna.

Far away from Jasimuddin’s beloved land, in Delhi, artist Sanjay Das has put up an exhibition of photographs representing the magnificence of rural Bengal.

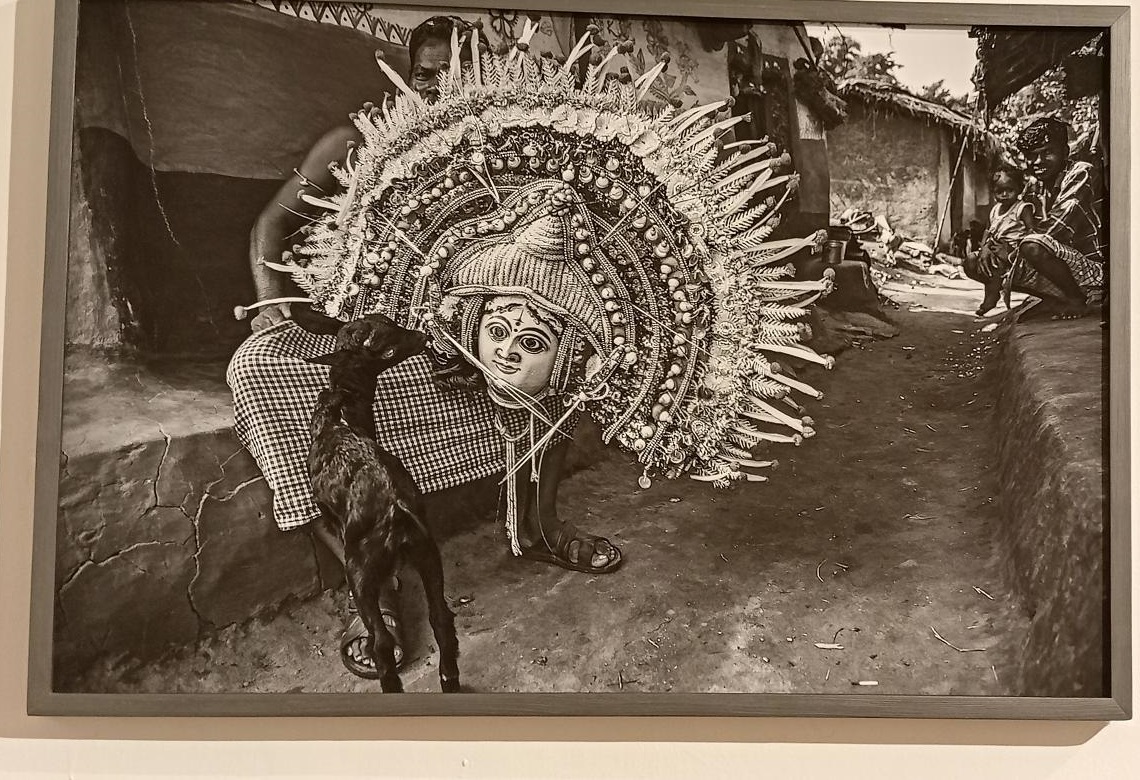

‘The Red Hibiscus Trail’ ventures into rural Bengal — the very heartland of diversity. The images and the incorporation of local art, such as dokra and patachitra, feel like scenes straight out of a Ritwik Ghatak film and evoke some of Jibanananda Das’s aesthetics of a beautiful Bengal.

Born and raised in the national capital to a Bengali family, Das had never been to West Bengal until 2011, when he was invited to present his work at the Birla Academy of Art and Culture in Kolkata. The one visit changed the course of his area of interest.

“Back in 2011, I was invited to a show in Birla Academy. I went there with my work and stayed in Kolkata for nine days. I went around the city taking pictures because I have read and heard so much. When I came back and showed those photos to my wife she was impressed. Then I started reading up about artists who have shown Bengal through their lens and I found that the representation is miniscule and limited to Kolkata, Howrah. I didn’t want to replicate anyone’s work and also wanted to explore my roots. That’s when I decided to start exploring West Bengal. So, the idea is to represent Bengal from Sandakphu to Sundarban,” says Das.

“Whatever you see at the exhibition is not urban Bengal at all. It’s all graam Bangla [rural Bengal]. This is only 25% of my work because there is a space constraint,” he added.

The exhibition does go beyond being a mere display – it serves as a platform for empowering rural artisans and ensuring that their craftsmanship receives the recognition it deserves.

“The images that have been blended with the local artistry are collaborative work. For example, an artisan came from Purulia and made the tushu. Same with the Kantha. A woman handmade it without the use of a stencil. Similarly, the patachitra work you see, the photo was first printed and taken to Pingla in West Bengal, and there the patachitra work was done by the local artisans,” he said.

The walk-through begins with two tusus featured at the entrance — one that is original and the other is the artist’s interpretation of it fused with the photos he clicked of the festival.

Tusu is a folk festival held on Makar Sankranti during which Tusu Devi idols are made from clay, hand painted by local artisans and then immersed at the end of festivities, with songs that have a melancholic tone.

Rural fairs are also organised during the festival, usually by the Kurmi tribal community. Tusu songs and a special dance are performed and celebrations continue for almost a month across villages in phases.

“There are multiple iterations of tusu — one is that there was a king in Kashipur who had two daughters who died. To keep their memory alive, unmarried women make these tusus and for a month, they sing Tusu and Bhadu (the two daughters) songs in regions adjoining Purulia,” said Saswata, Das’s son.

The series captures Bengal through a trail of the explored and the unexplored over a period of a decade, which he documented driving on a road from Delhi to Bengal and throughout the state.

While bringing out the quaint landscapes of Bengal, Das has also, in his endeavours, brought out the fading practices in his work.

One such is the ritual of Monosha Mangal, a festival dedicated to the snake goddess in rural Bengal.

Bengal is a highly fertile land of forests and rivers where encounters with snakes are not uncommon. Folklore has it that villagers began deifying snakes to battle the problem. It became part of their faith in ancient times. Such rituals are actively carried out in parts of the state. However, the expanse of it has been reduced to certain areas only.

To the artist’s credit, video insulations have been installed for viewers to enjoy the course of the rituals, including the folk songs and dances.

“I thought that these things were fading away. Sometimes a photograph is not enough to do justice to capture a moment, so I came up with these video insulations where they are singing these folk songs for ‘Maa Monosha’,” he said.

“A festival that has completely eroded because of modern problems. It is Jhaapan – a festival when snake charmers from across Bengal used to assemble and play the flute to charm snakes. It was stopped due to animal rights and all, but you cannot question people’s faith,” he said.

Contrary to the commercial Durga Puja celebrations, the festival is observed across the region in one but many ways, which have found a fine representation in Das’s works.

“Durga has many forms in Bengal. For example, patachitra Durga happens once in 10 years, then there is Shiva Durga in Kanya form, unlike Shakti form. Similarly, unlike the popular perception that terracotta temples are only in Bishnupur, they can be found across Bengal,” he said, pointing towards one of his photographs.

Among the many fast-disappearing rural festivals is the Charakh gajini mela, which is dedicated to the Charakh tree, which has been depicted in patachitra.

Elaborating on the idea, he said, “Inside an interior village near the Bangladesh border in Malda, while I was capturing the mela and its rituals for 30-35 hours, it struck me that in patachitra, artisans try to tell similar stories, so why not depict them in patachitra itself and give them their due respect so I collaborated with them?”

On similar lines, he threw light on the collaborative works on terracotta. “For an artist, telling a story through their work is supreme. It is the same for artisans. Through terracotta, they depict different stories which are not restricted to mythology but also expand to their everyday life.”

“The cultural side of Bengal is rich with its inter-religiosity. This aspect is getting lost in the loud political discourse. If you travel to the rural areas, you will find how diverse it is. You see, patachitra artists are mostly Muslims but they are all narrating mythological stories through their work. Similarly, in the Sundarbans, we have Bono Bibi (Queen of the forest), who is worshipped by both Hindus and Muslims. So, this is exactly what we want to talk about. I want my work to speak about the land and who it belongs to at the end,” the artist said.

Speaking on the curation of the exhibition, he emphasised how a ‘second eye’ helps filter through a photographer’s work. “Curator Ina Puri helped me to pick the best shots and stories. I am fortunate that a person like her, who has curated Nimai Ghosh, Raghu Rai and Bangladesh’s Shahid Ul Alam, has liked my work.”

The artist belongs to a family who performed the first Jatra (folk theatre that was part and parcel of Bengal) in Bengal. “So I grew up watching Jatra. I could connect so well because of my upbringing; otherwise, Bengalis in Delhi are far detached from their own culture. There is little interest in learning about their roots.”

A stellar image of an abandoned mosque in Bengal‘s Murshidabad stares at one of an empty boat engulfed by water plants. Both tell a story of neglect and silence.

“The architecture of this Fauti Masjid is not Mughal or Persian but Bengali. But they are not being taken care of. In rural Bengal, there are stunning images of mosques and Madrasas. The whole canvas is completely different and we should value it before it crumbles,” he said.