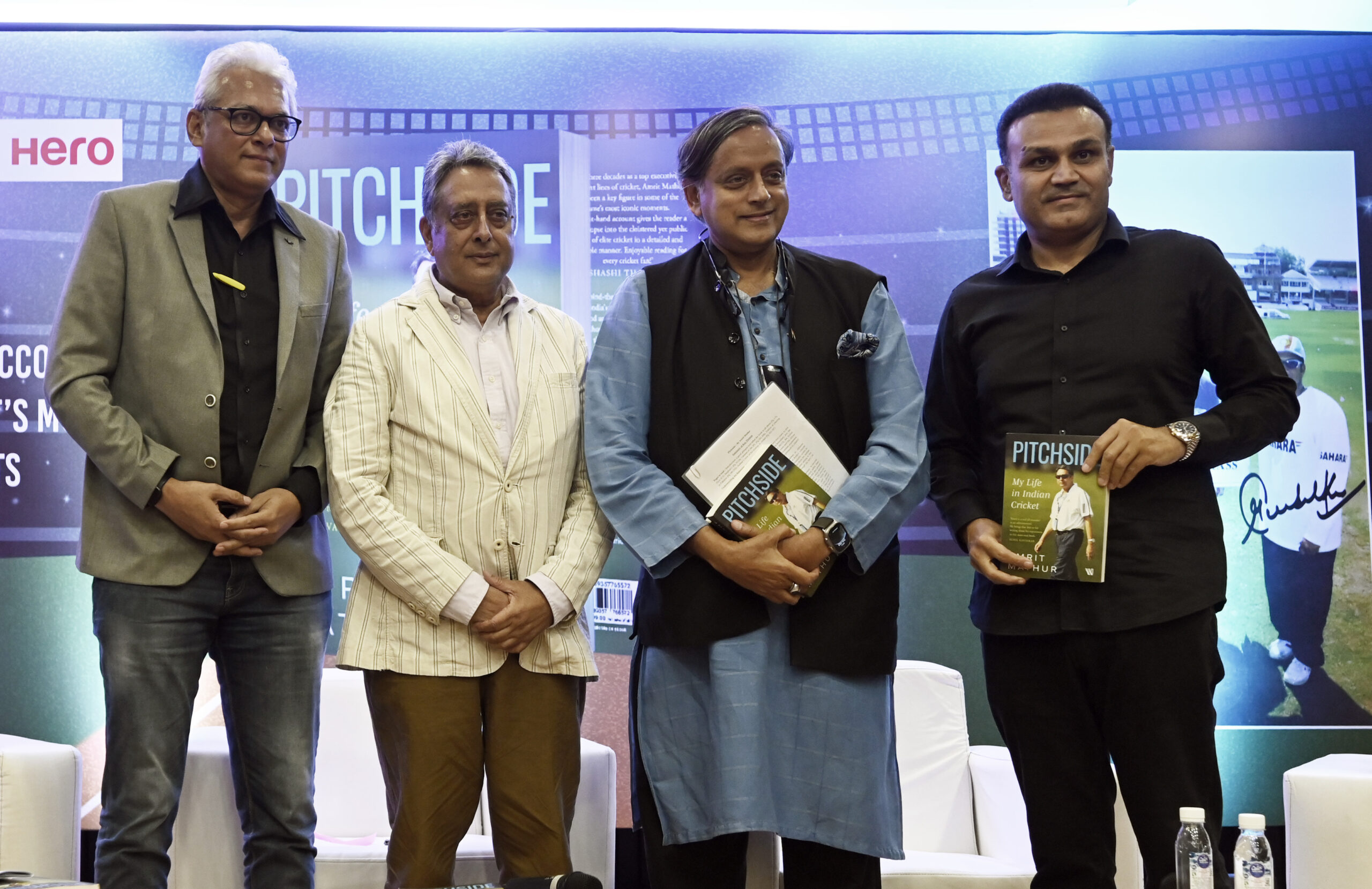

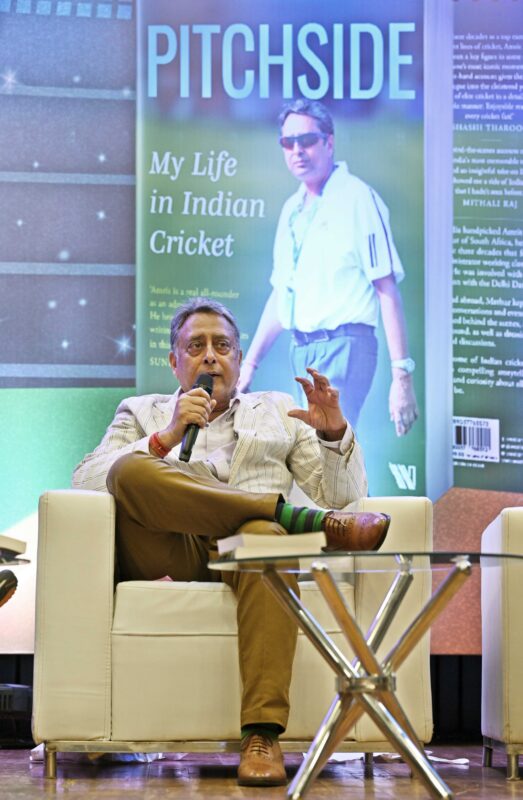

Amrit Mathur, a former civil servant, has worn many hats in Indian cricket and is therefore privy to many happenings within the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) and the Indian cricket team.

His book Pitchside: My life in Indian Cricket describes the rise of Indian cricket board from being pushovers against the ‘white bloc’ to a position of dominance. It also talks about India’s journey as cricket team that seemed on unstable ground in early 1990s under ‘old-school’, ‘relatively hands-off’ and ‘distant at times’ Mohammed Azharuddin to becoming a cohesive unit under a ‘democratic’, ‘grounded’, ‘self-confident’ but ‘insecure’ Sourav Ganguly with odd differences here and there among superstars in the team. And then to a top-notch side under MS Dhoni and Virat Kohli.

Mathur served as manager and media manager and was member of the 10-member 1996 World Cup organising PILCOM (Pakistan-India-Lanka Committee) in the decade-plus period of wielding power in BCCI.

He writes, “As BCCI official, member and employee, I had a season ticket to events that shaped Indian cricket.”

He describes his book as “a direct first-hand, eye-witness experience, not as someone-heard-something-and-told-me account”.

He is right. For he was ‘part of many firsts and landmark moments in Indian cricket’ like India’s historic tour of South Africa in late 1992 just when the African nation was returning to international cricket fold after isolation due to apartheid. He gives insight into how the Indian team, travelling to South Africa under Azhar and coach Ajit Wadekar, was underprepared about opposition players so much so that one player even asked “Who is Kepler Wessels’ even though the then South Africa skipper had played Test cricket for Australia with distinction earlier.

As team manager, he handled the off-field events since India, a side with players of colour, was the first team to tour SA after their re-entry. His role was no less than that of an ambassador and became so important that Sunday magazine even carried a column titled ‘The Mathur Mania’ on his activities there. The column is reproduced in the book.

Position of responsibility

Mathur mentions that South Africa’s tour of India in late 1991 for three ODIs, their first international tour after re-entry, was the first time BCCI realised the potential of TV rights.

Asked by the then BCCI president Madhavrao Scindia to find out a price to be quoted to South Africa cricket board’s Ali Bacher, who had surprised BCCI by offering money for rights to broadcast the three ODIs back home, he went to Board secretary Jagmohan Dalmiya, a hard bargainer, who told him to ask for $20,000 per game after the initial price had been set at $10,000.

Mathur, still unsure, told Bacher to quote his price and to his shock the South Africa cricket supremo offered $30,000 per match and raised it to $40,000 on his own, giving BCCI a whopping $1,20,000 for three games, a substantial increase from $30,000 they were looking at initially.

He writes proudly, ‘thirty years later, the value of each BCCI game is more than Rs 100 crore’.

Enroute, Mathur also details how PILCOM got a $10 million dollar guarantee – with $3.6 million as ready cash, sort of down payment – for the 1996 World Cup from WorldTel’s Mark Mascarenhas who risked his all. The $10 million was more than double of what the 1992 World Cup in Australia and New Zealand, had earned.

Mathur returned to the Indian team, this time as media manager for the 2002 NatWest Trophy. The entire chapter is interesting with enough light on players’ mood and nature.

In an early chapter of the book, he had described the Indian team he managed in the following words: “I observed that the team followed an undeclared hierarchy; its social construct respected seniority and success as recorded in the scorebook. Sachin Tendulkar was the first among equals for obvious reasons. The team’s traditions were enforced by the seniors, who led by example and nudged the juniors in the right direction. There was a clear code of conduct with protocols for seating, dress and punctuality which were backed by penal action, including monetary fines.”

The chapter on NatWest Trophy also touches upon the infamous scuffle between coach John Wright and batsman Virender Sehwag and how relations between Wright and skipper Ganguly soured over the latter reporting late.

Also, how differences were put on backburner with Wright taking backseat while overseeing and helming team’s three big tours that turned around Indian cricket.

The 2002 NatWest Trophy was the first of these three which India won. Mathur describes the tension in the dressing room after India were reduced to 146/5 before Mohammad Kaif and Yuvraj Singh took India to a memorable title victory at Lord’s. He also makes an important observation on how the then England captain Nasser Hussain had no say in the preparation of pitch at Lord’s unlike in India where captain and team management over-rule pitch curators.

He also writes on how the fitness culture changed in the Indian dressing room following the inclusion of foreign coaching staff, which Rahul Dravid supported, and how players adopted it.

The second such big tournament was the 2003 World Cup in South Africa where, after loss to Australia, the players’ houses – of Ganguly, Kaif and Rahul Dravid — were attacked by fans and former cricketers went ballistic in criticism.

Mathur writes, “Javagal Srinath wanted direct action against former cricketers”. He also explains how players were scared by over-the-top reaction.

There are interesting anecdotes on the World Cup, like how Dravid disliked the idea of India and Pakistan captains and teams shaking hands before the Centurion game as it was just another game for them and what the Indian team thought of Pakistan players. And how the Aussies after piling 359 in the final rubbed salt by practicing in front of the Indian dressing room ahead of India’s turn to bat. It also talks of the team room concept that developed during that World Cup.

The author also throws light on how the secular image of the team was protected prior to the start of 2003 World Cup.

“Sahara, the team sponsor, want the players to visit the Siddhi Vinayak temple. It’s Tuesday, an auspicious day, and a temple visit would make for a great photo. Wise heads question the wisdom of visiting a temple, pointing out that the cricket team represents a secular India. Is it, therefore, proper? Do you want to go? Sachin is asked. I have already done my prayers, he responds. The temple visit is vetoed.”

There is ample material on India’s 2004 tour of Pakistan, the third of these big turnaround tours, right from how the security was initially a concern before getting thumbs up, to a description of the cold war between Sachin Tendulkar and stand-in captain Rahul Dravid, who declared when the former was unbeaten on 194 in the first Test at Multan.

Consider these lines: “…other players stand silently on the balcony outside, deciding wisely to keep a safe distance from Sachin” or “At the end of play, one can tell that Sachin is still seething.”

There are characters like Virender Sehwag who make interesting comments to lighten atmosphere through these three tours.

Having seen the influx of money in Indian cricket first-hand and even propelled it initially, Mathur’s observation on IPL is crucial. He reveals that the idea for a franchise-based league was first mooted by Lalit Modi to him in the 1990s and it all looked set, but the then secretary Dalmiya shrugged it off as he wanted to keep BCCI strong and not cede power to private investors.

Mathur writes, “It became clear to me quite early that the BCCI leans towards control rather than cricket.”

He also talks about how BCCI has kept private franchise owners at bay and although they share the revenue, the league rules are decided totally by BCCI with the franchise owners not even in IPL Governing Council.

Stint at IPL

Mathur served as the head of operations of IPL franchise Delhi Daredevils (now Delhi Capitals) and recalls how challenging the job was – he faced four FIRs in first year and also ED investigation during controversy related to alleged money laundering by Lalit Modi, who he terms as an authoritarian giving ‘firmaans even at midnight’.

He also mentions the mistakes the Delhi franchise made with regards to releasing and picking players. “It is a standing joke that DD are good at spotting talent and great at managing it sloppily,” he writes.

In the chapter, ‘IPL: The Road Ahead’, he describes how IPL is threatening to turn international cricket into a series of international T20 leagues with IPL being the coveted tournament a la Wimbledon or The Open.

The last chapter is devoted to ‘Gamechangers’ or those who had big impact on the game, especially Indian cricket. Here he describes Tiger (MAK) Pataudi, Dalmiya, Tendulkar, Modi, Ganguly, Scindia, who brought him in cricket by making him Railways Sports Board secretary, Dravid, ex-Union minister and Delhi cricket body president Arun Jaitley, Gavaskar, Raj Singh Dungarpur and former Pakistan captain and Prime Minister Imran Khan. There are personal anecdotes.

True to his writing style, Mathur uses Hindi words and phrases throughout the book although not as much as he did in newspaper columns. He writes with wit and humour.

In true cricketing style, he writes, “I think of myself as a concussion sub, someone not supposed to play but unexpectedly pushed into the middle”.