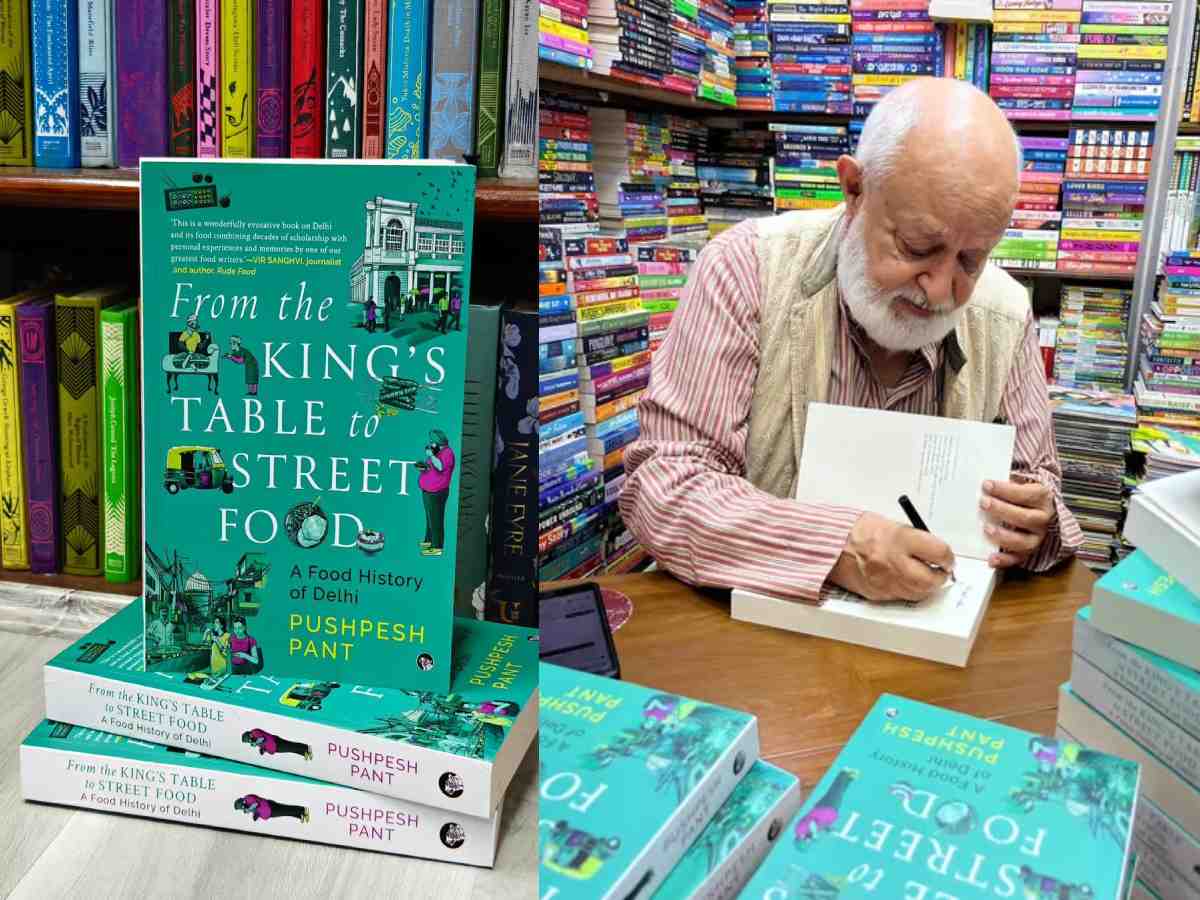

Pushpesh Pant’s latest book, From the King’s Table to Street Food, is not merely a collection of stories about food; it is a jharokha—a window into the rich history and cultural evolution of Delhi, seen through its culinary landscape. Describing his work, Pant agrees with this metaphor, stating, “I think you have captured the essence. It is like a jharokha, offering glimpses into the food and life of Delhi across different eras.”

The book takes readers on a journey through Delhi’s gastronomic legacy, charting its transformation from the 1960s to the present day. With meticulous detail, Pant illustrates how the city’s eating habits have mirrored its shifting social and cultural fabric. In the 1960s, iconic venues like the India Coffee House—popularly known as the Price Rise Resistance Movement (PRRM) Coffee House—were not just eateries; they were cultural hubs where intellectuals, artists, and writers converged. Here, food was much more than sustenance; it became part of larger conversations around politics, art, and freedom of expression.

Also read: Working without safety gear, manual scavengers stake their lives to earn a living in Delhi

Recalling the vibrancy of those times, Pant writes, “It was at India Coffee House that I first glimpsed the legendary painter MF Hussain, with his iconic foot-long brush in hand, and Dr Ram Manohar Lohia, surrounded by his admirers. It was more than just a restaurant; it was a truly democratic public space where dissent was voiced and disagreements aired with passion.”

In an interview with Patriot, Pant reflected on Delhi’s evolving cultural and culinary scene, emphasising the deep connection between food and the arts in earlier decades. “At Triveni Tea Terrace, artists gathered, while actors met at the National School of Drama (NSD) canteen. Sapru House attracted literary figures like Gulzar Sir and hosted festivals for Dhrupad, Kathak, and films,” he reminisced.

Pant also highlighted how dining options were often indicative of one’s financial standing. “If you had less money, you’d head to Bengali Market or Refugee Market dhabas. With a little more, you could dine at Triveni. NSD’s canteen was for those with connections, Sapru House for those on scholarships, and Rambles for salaried professionals.”

Beyond these observations, Pant delves into the historical culinary styles that once dominated Delhi, such as the bhatiyari style, which flourished in the sarais along the 2,000-km Grand Trunk Road. These sarais catered to the diverse palates of travellers. He also explores the staple dishes of the dak bungalows that emerged with the arrival of East India Company officials, and the elaborate food culture that grew around significant events, such as the Coronation Durbar of 1911, which temporarily turned parts of Delhi into grand cities celebrating royal events.

Pant further explains the fusion of regional influences that shaped Delhi’s cuisine, noting, “The Punjab border used to end at Delhi, and what we now call ‘Delhi food’ often has roots in Punjabi dhabas, which contrasts with the earlier Bhatiyar cuisine that was once dominant.” He adds, “Dishes like khamma dal, mutton tangri kebabs, and barra kebabs are now synonymous with Delhi’s food culture, but they actually hail from regions like Rampur, Patiala, and Agra, bringing with them strong Afghan influences.”

Pant’s book also acknowledges the contributions of lesser-known communities such as the Christian, Parsi, and Anglo Indian groups, whose migration to Delhi left an indelible mark on the city’s culinary heritage. The influx of South Indian flavours, particularly with the British officials, further transformed the city’s foodscape.

A key theme running through the book is Pant’s examination of how traditional classics—such as kebabs, tikkas, lentils, paneer, and milk-based desserts—have managed to endure despite the growing influence of multinational fast-food chains. He provides sharp insight into the resilience of Delhi’s food culture in the face of globalisation, observing that while trends may shift, the core identity of Delhi’s culinary world remains intact.

Reflecting on the modern food scene, Pant notes, “The food we see in Delhi today is largely borrowed from other regions, but what truly stands out is its diversity—it’s a mosaic of flavours and cultural representations.” He also discusses new trends, including the rise of food delivery services in the “Zomato era” and the influence of younger generations on the city’s food culture. When asked if the younger crowd has compromised Delhi’s food heritage, Pant firmly disagrees. “No, they haven’t ruined it. In fact, they’ve enhanced it. They have the money to spend and have experienced food from around the world.”

Also read: The fading tradition of shakkar ke khilone in Old Delhi’s Diwali celebrations

From the King’s Table to Street Food is, in essence, a celebration of Delhi’s evolving food culture. It offers readers not only a window into the city’s culinary past but also a thoughtful commentary on its present and future. The book is a must-read for anyone interested in the intersection of culture, history, and cuisine in one of the world’s most dynamic cities.

Pant concludes the book with a personal reflection on his own journey in Delhi: “This is the memoir of someone who came to Delhi as a young student and made it his home— transforming from a refugee from the hills into a Dilliwala, one who identifies with both the historic shehar and the ever-expanding New Delhi and NCR.”

Pushpesh Pant’s tribute to Delhi’s culinary history and evolution is not just a book—it is a journey through time, taste, and tradition. A must-read for those fascinated by the city’s dynamic blend of food, history, and culture.