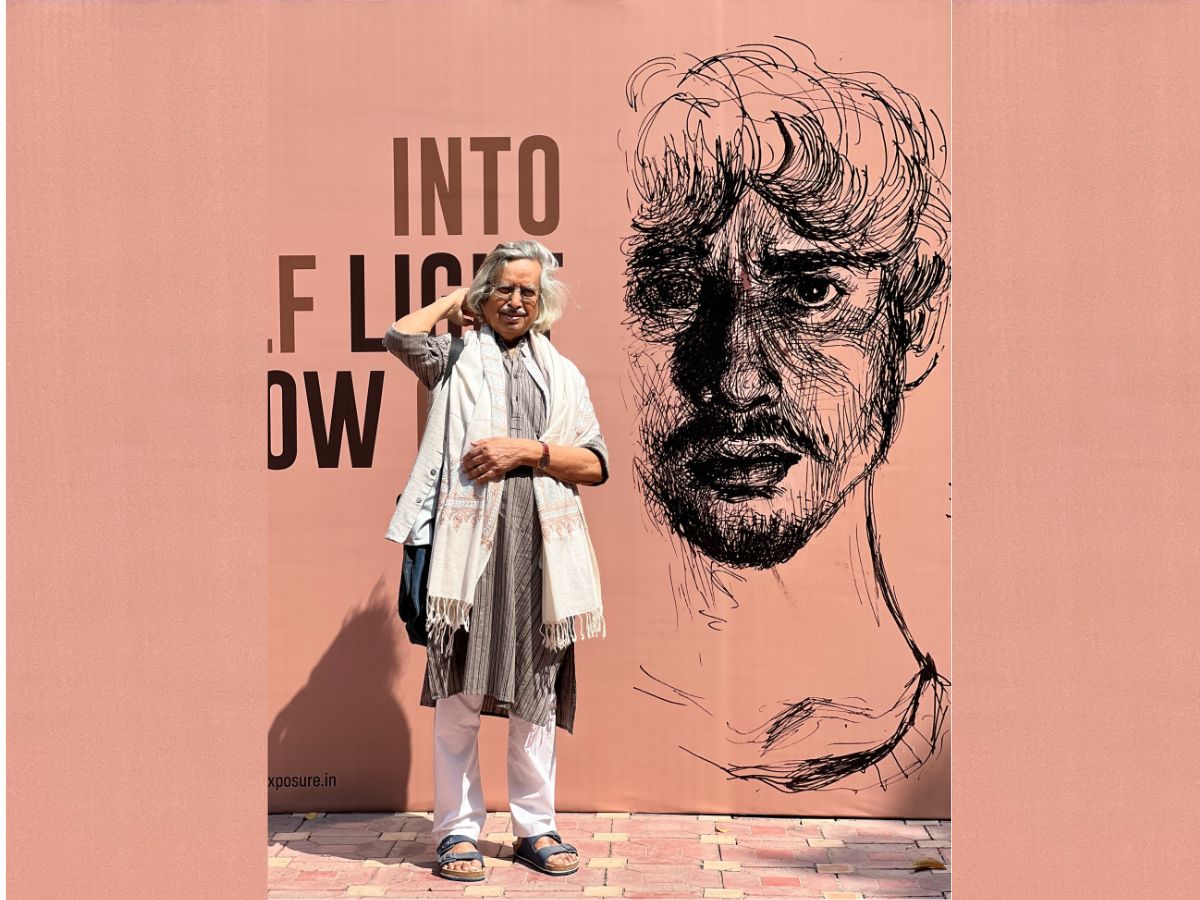

Painter Jogen Chowdhury was recently in Delhi for an exhibition, which he and several other artists conceptualised on Bengal to take its art beyond its own environment.

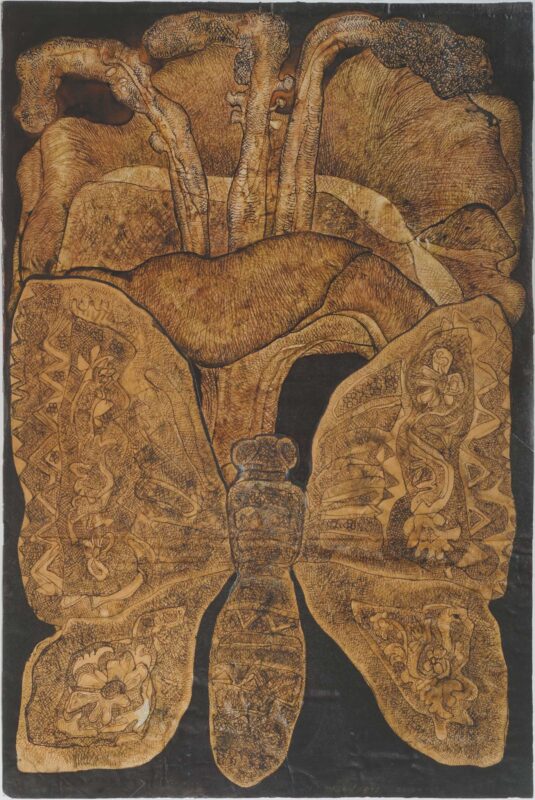

Responding to his own time and its social and political chaos, Chowdhury picked up ink and created moving allegories. His deeply stirring Sealdah sketches of refugees from erstwhile East Bengal are pertinent examples.

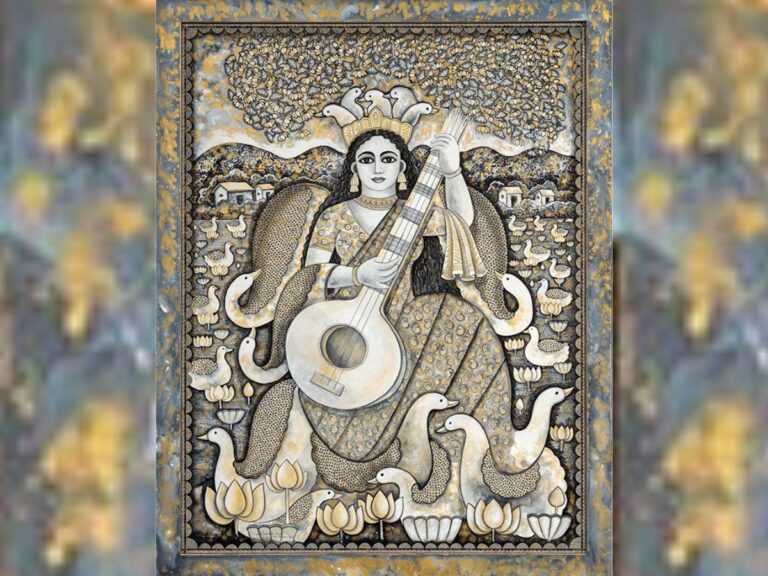

In his own words, his art has a form of ‘physicality’ — a sculptural feeling.

“The weight that is inherent in form in an object or in the human body. When I see an object, it physically vibrates in me,” said Chowdhury, describing his work.

His early works were mainly sketched in black to “personify the grim times Bengal saw during those days — from famine, to Partition, the following refugee crisis and dire poverty”.

It had cast a dark spell on his young mind.

However later, his art changed to incorporate modernity. At the exhibition in Delhi, he also reflected on how art looks like in the country today.

In an interview with Patriot, Chowdhury talks about his art and exhibition.

Excerpts:

When and how did you conceptualise the exhibition “Bengal Beyond Boundaries”?

It was conceptualised by me at the beginning of the year, along with few artist friends and art writers like Chhatrapati Dutta, Tapas Konar, Nanak Ganguly, Uma Nair and Vikram Bachhwat of Aakriti Art Gallery of Kolkata. We all felt that until now we have had no comprehensive exhibition of Bengal art outside Bengal and it is time that we organise the same.

When you say “boundaries”, what is meant by it?

It means that Bengal art has crossed the ‘boundary’ and reflects the openness in creativity in response to reality and the local environment.

You were influenced by the leftist movement in your early career. How much do you think it has shaped your art? Do you think it is important to have an ideology to create good art?

The basic ideals of the Left are humanitarian and as such I was deeply moved by them. In fact, in our lives we faced hard realities of life with difficult day-to-day problems, say, due to the Partition, when we migrated to West Bengal, while most of the Indians were not facing the same. It naturally is reflected in my art-works.

Ideology is surely important for one’s life but may not be essential for art, which is mainly based on aesthetic qualities of one’s expression.

Can we really call Indian modern art ‘modern’? For example, has it really contested the inhibitions and prejudice we have as a society, especially in terms of caste?

All contemporary art could be termed as modern. And all modern art essentially needs to be creative. Art is basically related to aesthetics and many artists are aesthetically creative artists, which is the main factor of art, I believe.

Art has to be creative. I think artists have not taken the responsibility of becoming reformers. They create art and may not act as social reformers. Many other artists, who wrote and discussed art, have played various different roles. This is why there are many artists who have directly or indirectly acted as reformers.

If you had to name one person who has immensely shaped how you see art, who would it be?

I always appreciate the writing and work of Rabindranath Tagore. I have been deeply influenced by his ideas right from a very early age.

In many instances, you have described Kolkata as a source of your inspiration after Partition. Could you elaborate on it?

I lived my early life and had my education in Kolkata after Partition when we migrated from what became East Pakistan. There were many educated middle-class people who came from East Bengal and enriched the city in art and literature, like Ritwik Ghatak, Mrinal Sen, Poritosh Sen and Sunil Ganguly. It became a vibrant city of creative activities in the field of film, literature and fine arts.

You have spent significant time during your early days painting at the Sealdah Station. How did the refugee crisis there find a place in your art?

I lived my early life and did my art education in Calcutta (now Kolkata) after Partition. While in art college I used to do large drawings and sketches of refugees staying in and around the Sealdah Station area, so naturally — my family and me being a refugee — this became part of my art.

How did Santiniketan and Kala Bhavan shape your art?

That I was staying in Santiniketan and working as a professor at Kala Bhavana naturally helped my artwork. Staying in such an atmosphere, which is imbued with the legacy and ideology of Rabindranath Tagore, gave me the right understanding as a growing artist.

How do you perceive new age art? Do you think that today’s youth lacks direction in art?

New age art is very diverse due to so many ideas and directions. In fact, the practice of art by a new generation of artists has increased manifold. As such there are too many young artists busy in this field. Today, I am sure there will be many more important artists who will work in the future. The many variations may look meaningless, but many more artists will be there who will create important artwork. No, I don’t entirely believe they are directionless. The many diverse directions art is taking will yield good results.

Apart from painting, you also write poetry. Could you share some of that experience? Or what gets you to write?

Actually, I am in the habit of writing poetry since my younger days. I was writing poetry during my high school and beyond. Since there were many cultural activities like writing poetry, performing theatres in and around the colony areas where I lived, it was natural to develop these habits. Such activities were common among people who came from East Bengal and lived in that area.