Those who visit the Parliament Library for the first time are often struck by its serene design and sense of scale. Beyond its architectural elegance, it is also among the country’s richest legislative libraries. Yet, few pause to ask who shaped the vision behind this grand space of learning.

At the forefront of that effort was Shivraj Patil, whose recent death has prompted renewed reflection on his institutional contributions. During his tenure as Lok Sabha Speaker from 1991 to 1996, Patil played a central role in initiating the creation of a modern library for members of both Houses of Parliament, a project that would take shape over the following decade.

Design competition

The architectural competition for the Parliament Library building was held in 1991, with noted architect Raj Rewal emerging as the winner. The project was considered prestigious, and Patil personally monitored the selection process and its early planning stages.

While construction was completed only in 2003 and the building was inaugurated on May 7, 2002, by then President APJ Abdul Kalam, the conceptual foundation and design approval were laid during Patil’s tenure as Speaker. Those associated with the project note that his involvement went beyond procedural oversight and extended to regular consultations during the formative stages.

Rooted in tradition

The Parliament Library is widely regarded as both an architectural milestone and a functional support system for legislators. Raj Rewal envisioned the structure as a “House of Knowledge” that would complement the circular Parliament House. He later said that the design drew inspiration from ancient Indian temples, blending traditional forms with modern requirements.

During this period, Rewal remained in close consultation with Patil. Their exchanges, according to those familiar with the project, helped align architectural ambition with parliamentary needs.

The building spans approximately 55,000 square metres. Its height was deliberately restricted to the podium level of the original Parliament House to preserve the visual dominance of the older structure, with only the domes rising above the skyline. At Patil’s suggestion, the exterior was clad in red sandstone to harmonise with the surrounding colonial-era buildings, while geometric jaali patterns evoke elements of classical Indian architecture.

Spatial philosophy

A senior Parliament official recalls that Patil, a keen student of Vaastu Shastra, took a personal interest in ensuring that the library’s layout reflected traditional spatial principles. The triangular form of the building, symbolic elements at entrances, and the central courtyard were intended, the official said, to create a balanced and positive environment for study and deliberation.

These considerations, officials note, stood in contrast to the original circular Parliament building, which some traditionally inclined planners had viewed as less compatible with Vaastu principles.

Working space for legislators

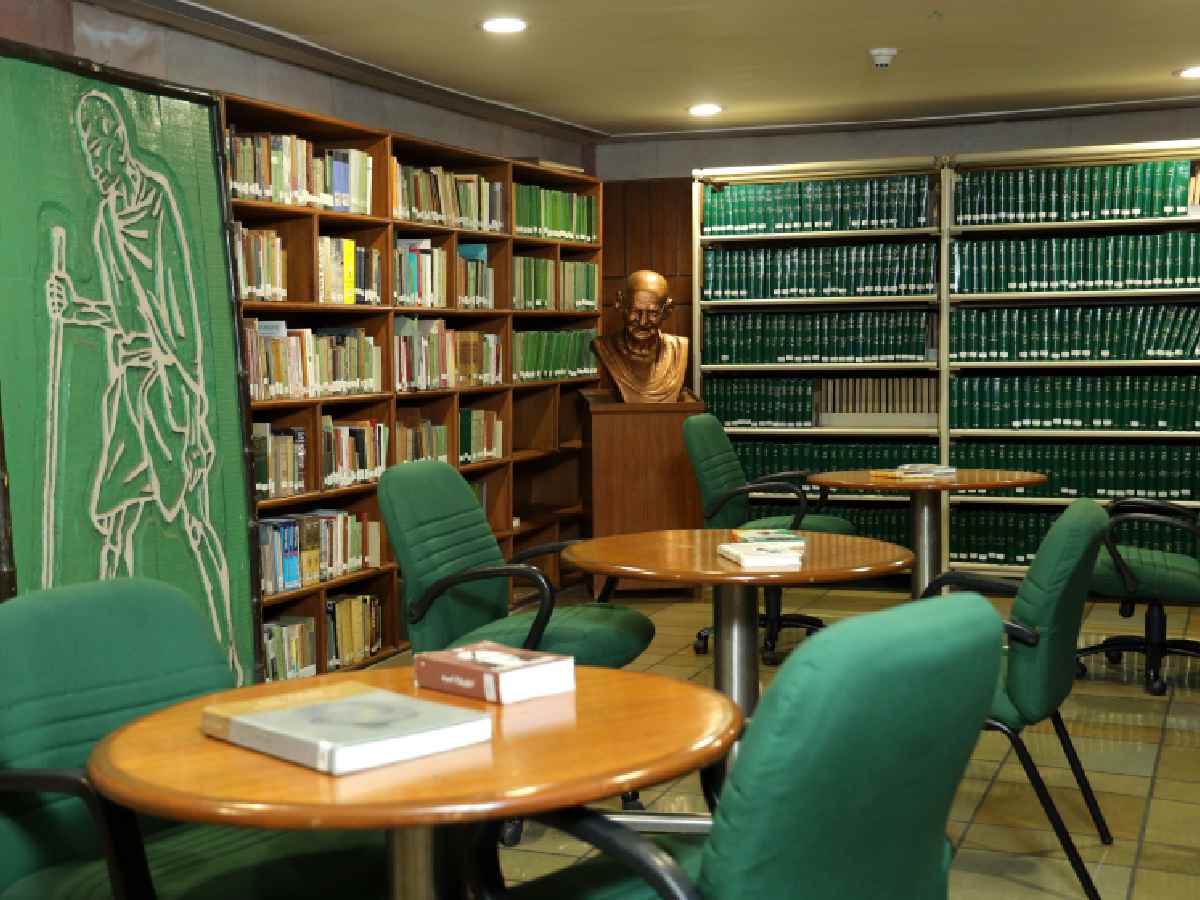

Former BJP leader Jagmohan often described the Parliament Library as a vast repository that strengthens legislators’ work. The facility includes a digital library equipped with multimedia resources and satellite links, allowing Members of Parliament to access global information quickly.

For instance, MPs preparing for debates on subjects such as environmental policy can consult reports, datasets, and audiovisual material on site. The Scholars’ Library, the largest reading area within the complex, offers a quiet space for sustained research. Natural light filtering through the domes reduces visual fatigue and aids concentration, regular users say.

Place of learning

Even after ceasing to be Members of Parliament, figures such as Khushwant Singh, Kuldeep Nayar, Pranab Mukherjee and Syed Shahabuddin were known to spend long hours at the library. Shivraj Patil himself, whenever he visited Delhi, made it a point to study there.

The space has also served as an informal meeting ground where MPs hold discussions that help build consensus on legislation. Seminars and lectures in the amphitheatre allow parliamentarians to engage with scholars and subject experts beyond the pressures of the House.

Patil’s personal involvement extended to advising library staff on book acquisitions. During his tenure as Union Home Minister, he would often spend hours studying there, sometimes late into the night, particularly when preparing statements or interventions in Parliament.

Enduring institutional contribution

Raj Rewal’s design is widely seen as more than an architectural achievement; it is a functional extension of India’s democratic process. A project initiated under Shivraj Patil’s leadership has evolved into a lasting institutional asset that supports research, dialogue and informed law-making.

It is worth recalling that Rewal first gained national recognition with the Hall of Nations at Pragati Maidan, designed in the early 1970s along with the Hall of Fame and the Nehru Centre. These structures, later demolished during Pragati Maidan’s redevelopment, were widely regarded as icons of India’s modern architectural heritage and had been exhibited internationally, including in New York and Paris. Their loss deeply affected the architectural community, and Rewal himself was reportedly distressed by their demolition.

At 91, Rewal was said to be deeply saddened on hearing of Shivraj Patil’s passing. Together, the two men left behind a distinctive and enduring imprint on the Parliament complex. Notably, Patil never sought personal credit for his role in shaping the Parliament Library, preferring instead to let the institution speak for itself.