Films like Pichla Varka, Sunder Nagri and Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon capture the multi layered nuances and contradictions that Delhi has to offer

Racing down the roads of Delhi in high speed cars in broad day light, with the Delhi Police in equally swanky cars on their chase – logic takes a back seat in Dharma Production’s recent Netflix release Drive.

Clearly the filmmakers are not much aware of Delhi. Or perhaps simply chooses to dismiss the notorious traffic of the city, to allow their cars zoom down the Capital’s roads. Drive makes the city almost unrecognisable to suit its story.

Starkly different from this and much closer to reality, are films like Pichla Varka, Sunder Nagri and Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon that captures the multi layered nuances and contradictions that Delhi has to offer.

Part of the films screened at the sixth edition of Urban Lens Film Festival, they explore the urban condition, “From the granularity of everyday life to a macro picture of what it means to inhabit a city,” – this is the objective of the festival.

While these three films are diverse in their genre, form and story-telling, what unites them is the authenticity and essence of the Capital that it puts on the table.

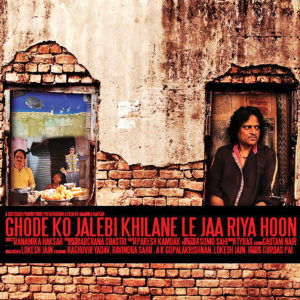

Parting from the usual narrative of the city that is prominent in most Hindi movies, Anamaika Haksar’s feature film – Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon, balances the line between fiction and non-fiction.

An ode to the multiplicity of Old Delhi, this film is based in the cramped and busy lanes of what used to be called Shahjanabad (1639-1857). Capturing the dreams and despairs of the many lives inhabiting Old Delhi, the film follows four main characters: a pickpocket, a vendor of sweet and savoury snacks, a labourer-activist, and a conductor of heritage walks.

The films show Old Delhi through their eyes. Deduced from the various interviews of people living in Shahjanabad area, it portrays the lives, hopes and aspirations of those toiling there. Keeping it real, it features the various languages and dialects, with the choicest of abuses that is a part of their daily lives.

Patru, the pickpocket, decides to take people on alternative walks, showing them the underbelly of the city, they think they know, but this lands him in trouble with local merchants and the police. He then finally decides to conduct one last ‘Dream Walk’. It is here that the film delves into the subterranean consciousness of the city’s migrant population. Together, these walks create a visual and aural history of Old Delhi from different points of view. And when Lali, the labourer-activist, too joins the fray, giving a speech urging workers to unite, he lands them all in jail.

A noted theatre director, Haskar implements the style of documentary with fantasy and theatre. “Fusing documentary-realism with magic-realism, and true and fictionalised stories with poetry and dreams, it is a love-letter to the syncretic culture of Old Delhi, to its history which is slowly losing itself amidst concrete and smog. It is a paean, also, to the so-called ‘little people’ – the migrants, the small vendors, the daily-wage-earners – who are relegated to the fringes of society even as they try to make their way through life with dignity, good-humour and courage,” adds Haskar.

Talking about those who have been pushed to the side-lines of the society, another film Sunder Nagri follows the lives of a small working class colony living on the margins of Delhi.

Delhi plays the central character in this movie. Most families residing in Sunder Nagri come from a community of weavers. The last ten years have seen a gradual disintegration of the handloom tradition of this community under the globalisation regime. The documentary captures the struggles of two family of weavers as they try to cope with the changes of globalisation.

Following the lives of Radha and Bal Krishan who are at a critical point in their relationship, Bal Krishan is underemployed and constantly cheated. They are in disagreement about Radha going out to work. However, through all their ups and downs they retain the ability to laugh.

Exploring yet another aspect of Delhi that led to the growth of the city to what it is today, Pichla Varka depicts the stories of women partition refugees.

“The film was shot in my house in Kirti Nagar, where my grandmother and her friends have been playing cards every afternoon now for the past 30 years,” says director Priyanka Chhabra.

Chhabra’s grandmother and her friends share a common history, of being Partition refugees who came to India after the state of Pakistan was created and eventually settled in Delhi. The last generation of people who can ever tell us again what the partition of Punjab was like, or what even pre-partition India was like, the film documents first hand experiences of the pangs of Partition faced by women.

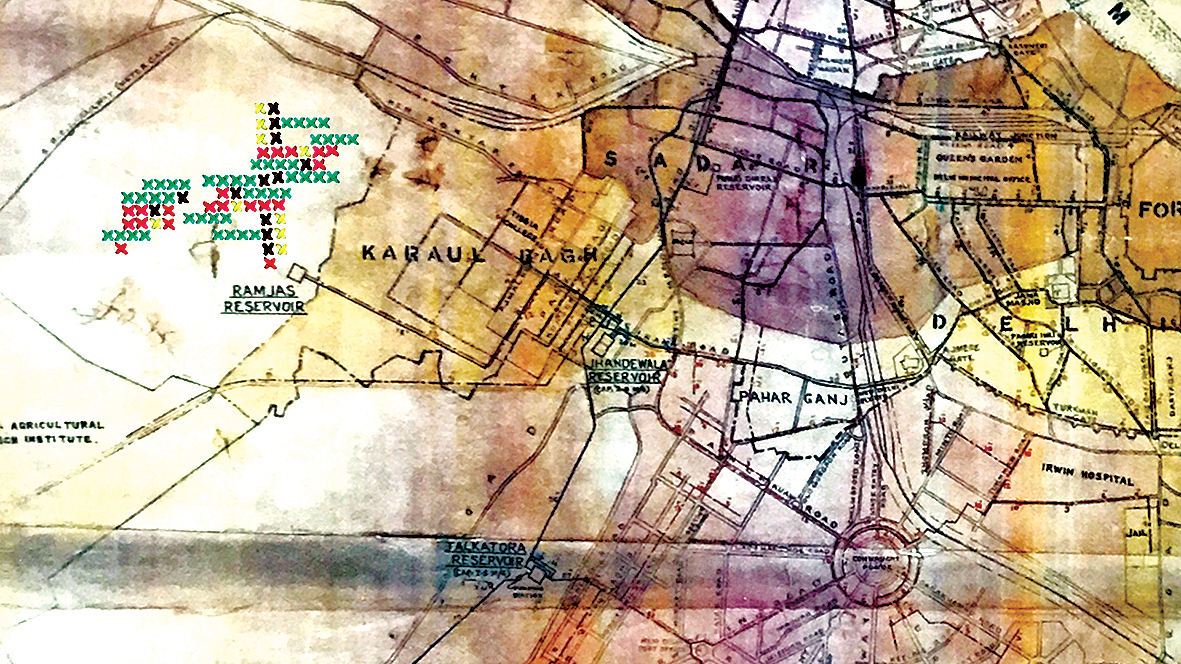

Based in a West Delhi neighbourhood, Pichla Varka looks at the experiences of ordinary women who experienced the violence and uncertainty of leaving their their mulk (homeland) to enter a new country in 1947. How history play out on ordinary lives and where do households and properties merge, are few of the questions that the documentary attempts to address.

With different stories, these films successfully manages to capture the medley of scenes that are unique and intimately close to Delhi.