A humongous banner hangs above the entry point of Madrasi Camp near the Barapullah drain. A chorus of voices rises along the road leading to the settlement, which unfolds into a scene reminiscent of a small hamlet in Chennai. Tamil text adorns nearly every house’s wall, a visual reminder of how distinct this community is from other slum clusters in the capital.

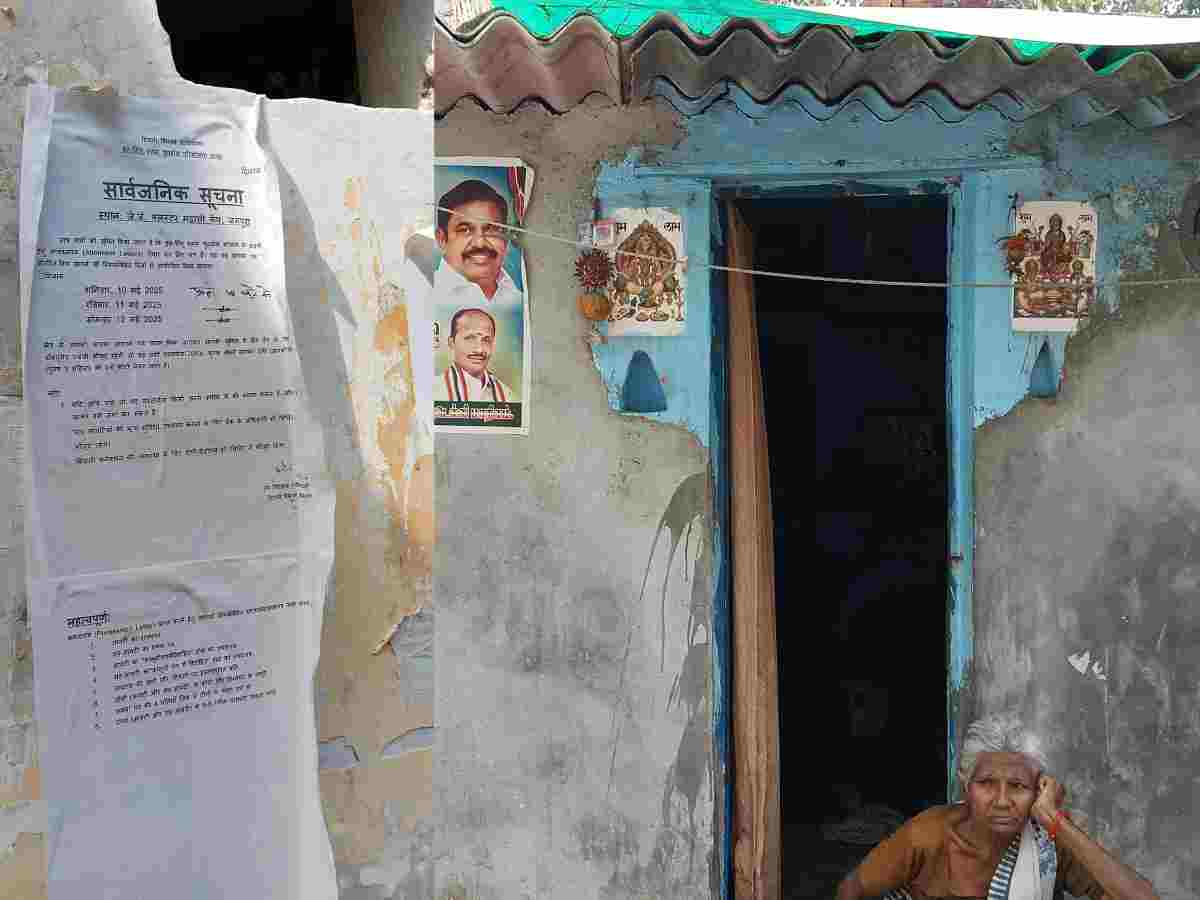

A piece of Tamil Nadu lives on in each corner of the settlement, which houses 370 households, according to residents. Those who remain hold fast to the traditions and customs that keep them connected to the homes they left behind. Cultural iconography, such as Kirtimukha—a demon mask typically seen across southern India—adorns many doors. The swallowing face, sharp fangs bared, serves as a guardian, protecting inhabitants from evil spirits even here in Delhi.

Beyond these cultural masks, a poster of the regional party, the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), is displayed on one house’s wall. “I had always liked Jayalalitha. I keep her as a reminder of my homeland,” said Kulamma, nearly 72, speaking in Hindi honed over the years—although her accent often gives her away.

Demolishing Madrasi Camp and its cultural legacy

That cultural legacy is now under threat. Classified as an encroachment, Madrasi Camp is slated for demolition by June 1. Residents have been ordered to evacuate by May 29. With days numbered, families are rushing to gather their belongings and seek alternative shelter.

On September 5, 2024, the Public Works Department (PWD) issued eviction notices to residents, giving them just five days to vacate. This sparked outrage. On September 8, 2024, then Chief Minister Atishi intervened, stating that the demolition was illegal. Madrasi Camp, she noted, is a Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB)–notified JJ cluster located on Railway land, making its residents entitled to rehabilitation.

The Delhi High Court issued a notice that same day, staying eviction and ordering the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) to substantiate its claim that the camp blocked water flow in the Barapullah channel.

While the Irrigation and Flood Control Department (IFCD) submitted a report on October 5, 2024, alleging the settlement obstructed the drain, a fact-finding team of engineers from IIT Delhi and IIT Bombay concluded that the actual obstruction stemmed from the nearby flyovers and bridges, not the settlement.

Delhi HC verdict and directives

Despite these findings, the Delhi High Court initially set a demolition deadline of May 10, later extending it by a day to allow residents more time to relocate and for the government to ensure necessary amenities were provided.

The court instructed that demolition must be carried out systematically. It directed the DDA, Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD), DUSIB, PWD, and the Government of the National Capital Territory of Delhi to organise two camps between May 10 and 12. The first camp was for handing over possession letters for the Narela flats, and the second was for sanctioning loans, if needed.

“… the representatives of banks shall be duly present at the camps so that if any of the dwellers wish to avail of loan facilities, it can be arranged without inconvenience,” the court ordered.

It also directed the DDA and DUSIB to ensure amenities are available in Narela by May 20.

After that date, the court directed, Madrasi Camp residents “shall start moving their belongings to the respective flats allotted to them in Narela,” adding that those who did not accept possession letters or loan assistance “shall not be granted any further opportunity to seek allotment of the flats at Narela or any rehabilitation camps”.

Only 189 receive flats, others left out

Still, for many, no relief is in sight. Only 189 households have been found eligible for flats in Narela, located nearly 50 km from the Jangpura slum cluster. “The selection was extremely arbitrary. It seemed like they did not want to give us any house. My family is not eligible for any loan either, since it was only for the residents who are being shifted to Narela,” said Revathy, nearly 40, as she worried about her family’s future. “They were checking for our voting history, although we had all our papers. They just said that since I did not vote in 2014, I was not eligible. I have voted all throughout the other years,” she added.

Narela: Far from a dignified life

Even those who have been allotted homes in Narela feel far from reassured. Nearly 70-year-old Kulamma lives alone, her children having returned to their hometown in Kallakurichi, Tamil Nadu. The thought of life in Narela fills her with dread.

“All of us who were allotted houses in Narela visited the place. We found out that there is no water connection. Even for basic use, we had to buy water from vendors. They charge Rs 30 for 12 litres, which comes in buckets. With that, we must manage drinking, bathing, and everything else,” she said.

Returning to her sons is not an option. “My son has taken to alcohol now. He has a violent streak I cannot control. It is better to live here alone than stay with them,” she said. “Lekin, Narela jana kisi shamshanghaat tak jaane jaisa hi hai (Going to Narela is like going to the cremation ground),” she murmured.

Jobs, education and family structures at risk

Some residents remain hesitant to move to Delhi’s north-western outskirts. Shiva, a contractual employee with the MCD, voiced concerns about losing his livelihood. “I have been a resident here at Madrasi Camp since 1985. Before that, I was in Tamil Nadu. That means I’ve lived here for about 40 years. My work and my rozi roti are here. If I move to Narela, I’ll either have to find work there or travel six hours daily just to survive. They say we can apply for a loan to cover Rs 1.4 lakh, but where will I get the money to pay the interest if I don’t have a job?” he sighed.

Parents also worry about their children’s education. “Narela does not have any Tamil-medium schools. Most of the children here attend a nearby school that teaches in Tamil. If we move, I don’t know what will happen to their education. They might have to start all over again. I’m not even referring to the financial constraints,” said a resident, requesting anonymity.

Also Read: Breaking glass ceilings and law: Delhi’s women drug lords

All the children in the camp attend the Delhi Tamil Education Association’s (DTEA) school in Lodhi Estate, paying Rs 250 a month. School officials say DTEA has served Tamil families in Delhi for over a century, offering instruction in Tamil, Hindi, and English to keep the community immersed in their culture.

Venbi, 60, stood consoling her neighbour Kumari, whose application for a flat was rejected because her husband—listed as a co-owner—was not present. “My husband did not stay with me. He abandoned me when I needed him. I raised my sons into men, but now I have to show proof of my husband? I don’t even know where he is,” Kumari said, fuming. Unfortunately, both names are registered as household owners, and both must be present to qualify.

Beautification at the cost of the poor

All odds seem stacked against the Tamil residents of Madrasi Camp. Their homes, livelihoods, and dignity are at stake—while unauthorised colonies in more affluent areas remain untouched.

“They’ve been cleaning up the river bed at Barapullah for the past 10 months. Nothing has changed. The drain still stinks and debris keeps floating. If they wanted to improve things, they would have made sure poor people could live with dignity,” said Wasim, a vendor from Sarai Kale Khan who operates near the camp. He, too, now faces an uncertain future.

“Beautifying Mughal-era architecture is fine, but it shouldn’t come at the cost of the poor,” he added.

Established sometime between 1968 and 1970, the Jangpura settlement of Madrasi Camp is on the verge of being dismantled. What will be lost is not just a cluster of houses, but a living, breathing cultural identity that may never return.