The National Crafts Museum & Hastkala Academy, located at the corner of Pragati Maidan opposite the majestic Purana Qila, celebrates India’s rich, diverse, and living craft and weaving traditions. Designed by renowned architect Charles Correa, the museum is not just a repository of artefacts—it is a vibrant space where India’s artistic legacy continues to breathe.

The museum’s architecture itself echoes traditional design, with open-air exhibits and galleries that house thousands of handicraft and handloom artefacts. Visitors can witness the intricacies of craft-making under one roof, with the added opportunity to purchase souvenirs directly from artisans and weavers on site.

A repository of craft across states

The museum’s collection comprises over 29,395 specimens acquired over 70 years, sourced from states and Union Territories across India—ranging from Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Gujarat, and Tamil Nadu to Jammu & Kashmir, Ladakh, and Puducherry. It reflects the enduring legacy of India’s craft and handloom traditions across centuries.

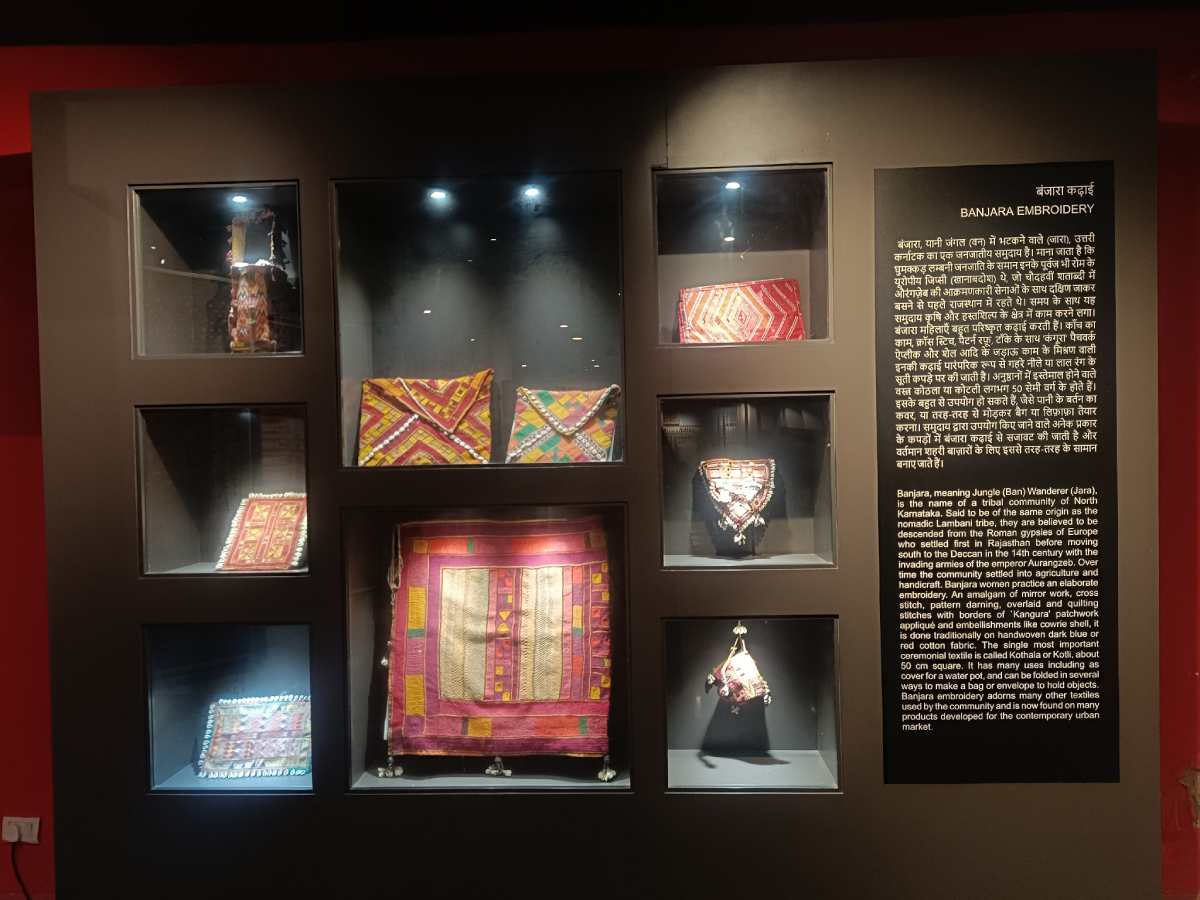

This diverse collection includes textiles, metal sculptures, woodwork, tribal paintings, bamboo and cane crafts, terracotta figures, and much more. Among the standout textile exhibits are Kalamkaris, Jamawars, Pashmina and Shahtoosh shawls, Kantha and Chikankari embroidery, Bandhani fabrics, Baluchar and Jamdani saris, Pichwais, Phulkaris, Odisha Ikats, Chamba Rumals, block-printed textiles from Gujarat and Rajasthan, Himru pieces from Maharashtra, Naga shawls, Chanderi saris, and tribal weaves from the Lambadi, Toda, and Naga communities.

Why August 7 matters

August 7 marked National Handloom Day, commemorating the launch of the Swadeshi Movement on this day in 1905 at Calcutta Town Hall—a protest against the British partition of Bengal. To provide more context, Patriot takes you through the textile galleries of the National Crafts Museum.

Fondly referred to as a “live museum” by visitors and experts, the space offers a sensory and participatory experience. From house replicas, artefacts and utensils to live crafts demonstrations and folk performances, the museum presents a holistic view of India’s indigenous and tribal life. Every month, 25 artists are invited to conduct pottery, handloom weaving, and over two dozen hands-on activities for the public.

Also Read: Couture on a Roll

Two galleries, one living tradition

The museum houses two dedicated spaces—Textile Gallery and Textile Gallery II—each offering a unique lens into India’s textile heritage.

The first textile gallery is curated to celebrate the richness of Indian textile traditions and serve as a design and learning resource. Over 200 types of textiles are displayed here, organised into three categories based on the design stage: Pre-Loom, On-Loom, and Post-Loom.

The Pre-Loom section introduces visitors to the design stage before weaving, where patterns are imagined and transferred to the yarn. The On-Loom section covers weaving itself, showcasing brocades, muslin, jamdani, and woven sarees and shawls. The Post-Loom area features hand-painting, printing, and embroidery techniques applied to finished cloth.

The gallery’s entrance features Mahatma Gandhi and tools used for making khadi, alongside exhibits explaining the significance of natural dyes and the traditional use of Himalayan resources for dye-making.

On a recent visit, Patriot witnessed artisan Javed Ahmed from Banaras, Uttar Pradesh, weaving white fabric on a handloom. “These are like toys for me,” he said with a beaming smile. “My ancestors have been using these looms for over 400 years.”

From Kashmir’s Pashmina to Banjara embroidery, the gallery features textiles from almost every state. Water pot covers, fabric bags, and envelopes are also on display, adding layers to the narrative.

Behind the main wall are two towering panels displaying Sujni craft, a traditional art form from Bihar made using recycled fabric. A visitor named Shikha, speaking to Patriot, said, “I came here just to explore, but I’m a big fan of textiles. My father is a fabric retailer in Bihar. It makes me proud to see the clothes I’ve worn since childhood have so much history.” Shikha hails from Motihari, Bihar.

One of the gallery’s gems is a centuries-old Jaynamaz (prayer mat of Muslims), hand-loomed in the style of a Turkish carpet using red and cream.

Whether block prints or brocades, many of these designs have evolved over time. Yet in this gallery, they remain steeped in pride, telling timeless stories.

Textile Gallery II explores the dynamic evolution of Indian textiles, highlighting how tradition adapts to time. The Sanskrit word parampara means tradition, but in India, textiles have never followed a fixed formula. They have developed across regions and centuries through block printing, ikats, brocades, embroideries, and resist-dyeing—shaped by geography, demand, and cultural exchange.

With colonialism and global trade came modernism—minimalist designs and muted palettes. Yet Indian weavers adapted, blending modern design with traditional sensibilities, often in collaboration with formally trained designers.

This gallery celebrates that interplay of tradition and innovation.

Faith woven in thread

Among the most compelling exhibits is a 9–10 metre-long Kalamkari piece depicting the Ramayana, hand-painted in rich detail. Close by are depictions of the Mahabharata and the story of Prophet Moses, believed to be from the 17th or 18th century.

Another wall features an embroidered portrait of Maa Saraswati, while a set of vibrant fabric-crafted shoes in royal hues—red, purple, gold—suggests links with regal attire.

Tracing textile ornamentation

At the heart of the gallery, 7–8 glass cases display the evolution of textile embellishments—from stonework and laces to latkans. These include stone-engraved kurtas from Gujarat, latkan-adorned cholis from Rajasthan, and ghagras with lacework, all dating back to the early 17th century.

The Bandhej or tie-dye technique—originating in Gujarat and later embraced in Rajasthan—is also showcased. Once featuring sober patterns with vibrant hues, Bandhej remains a widely loved ethnic style today.

Other treasures include zari-embroidered leather juttis, zari brocade caps, glasswork cholis, and geometric-patterned fabrics by Vishwakarma artisans. A replica bedroom display highlights the use of silk and zari in bedsheets, cushion covers, and pillowcases.

Also Read: Bundelkhand tribal food festival brings forgotten flavours to Delhi

A conversation with Col Manoj Rana

Speaking to Patriot, Senior Director Colonel Manoj Rana reflected on the museum’s evolution and activities. “The Textile Gallery II was launched in the first week of August 2024 to honour Handloom Day. It’s now completing one year.”

He added, “The aim of Hastkala Academy is to promote India’s heritage and crafts by conducting courses and engaging activities for students, the younger generation, and visitors. We have looms activated as part of a continuous process. Block printers and other artisans come to us every month as part of our craft demonstration programme. We call 25 artisans each month—across pottery, handloom, painting, and artefacts. That’s why it’s called a live academy.”

Rana explained the curatorial process: “We have nearly 30,000 artefacts in storage, with about 3,000 on display. These rotate once a year or once in two years. The displayed pieces are selected based on uniqueness and relevance. We also consider new commissions and acquisitions, assessed by our expert advisory committee.”

On the museum’s broader role, he said, “We have four types of galleries: the Folk and Tribal Gallery, the Textile Galleries I and II, and the Cultic Gallery which features religious artefacts used in rituals across India. These galleries showcase how India’s traditions have evolved while staying rooted.”

Rana added, “What makes the museum special is that we are preserving living traditions—ones still practised across different regions. This is not just a museum of the past; it’s a bridge to the present. Visitors leave with the realisation that many of these crafts are still part of India’s cultural fabric.”