Filmmaker Praveen Mochchale gives an insight into the challenges of making indie films and his way of storytelling

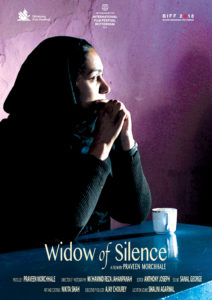

National Award-winning filmmaker Praveen Mochchale’s third feature Widow of Silence refuses to slow down on the international festival circuit. Having already won accolades at Kolkata International Film Festival, MOOOV Festival, Belgium and Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles as well as Ottawa Indian Film Festival, the film has now got selected for the International Competition at the prestigious Mannheim-Heidelberg Festival, Germany. The film, starring noted theatre actor Shilpi Marwaha in the eponymous role, revolves around a Kashmiri half-widow who lives with her 11-year-old daughter and ailing mother-in-law.

In this interview, Morchale talks about the challenges of making films on sensitive subjects, importance of accolades in boosting the prospects of indie films, his collaboration with the Iranian cinematographer Mohammad Reza Jahanpanah, and his fascination for the long take.

Excerpts:

Your film Widow of Silence tackles a sensitive subject that has already been touched upon by various fiction and non-fiction films in the recent times. How is your film different? Why did you choose to make it in Urdu?

I feel my cinema raises questions about life, society and status quo without being melodramatic and judgemental. As a filmmaker, showing critically important issues of ordinary people — impartially and truthfully — which is often not easy nowadays for artists, is of utmost importance for me.

I believe my way is showing rather than telling. I rely on subtlety of language laced with satire, and that is where I believe my film is quite different from other films. I feel satire is a very effective tool, if used properly.

I have noticed that Kashmiris are very artistic and poetic people and they have a long history of art as a way of life. I chose to make Widow of Silence in Urdu as Kashmiris speak Urdu very much and express themselves beautifully and poetically in Urdu as well. As I work with locals, who are non-actors and are mostly dwellers of the villages, using their own language and dialect makes them much more comfortable to express from within.

Widow of Silence is not a political film but it does have a strong political commentary? How does one make such a politically relevant film without drawing the censors’ attention?

I believe a film should make us understand a different world of ordinary people and connect us with them through a different perspective. Also, it should take us on an unknown terrain of emotional, social and spiritual journey, thoughtfully. Anything critical to status quo is always political, even if it’s true.

As a filmmaker, I think I should not be judgmental and start giving the solutions to problems through films. Although as a person I have my strong opinion and biases, I just like to show the reality in my films. When art has so many restrictions, one has to be smart to find out ways to say what one wants to say. So, I show things with a great sense of neutrality without taking any side, else it makes cinema a tool of propaganda and loses its importance. Showing truth as it is needs a lot of conviction and fearlessness in present times in which we are living.

Mannheim-Heidelberg Festival has a long history of backing indie filmmakers, having served as the launch pad for great directors like Satyajit Ray. Tell us about the challenges of showcasing one’s work at such an important global forum.

I am happy that Widow of Silence is selected for the International Competition at the prestigious Mannheim-Heidelberg Festival — which is worldwide known for discovering the new auteurs of art house cinema. Many greats of world cinema like François Truffaut, Krzysztof Kieslowski, Jim Jarmusch, Thomas Vinterberg, Helke Sander, Atom Egoyan, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, among others, were first discovered at the festival.

It is very important that we should make our cinema in our own way to reach the world stage. Our local stories have many strong universal connects. The way we show the art and craft of cinema must have some signature. I believe my cinema is very visual, unsentimental, simple, subtle, and devoid of drama but it has its own soulful way to touch the audiences. This can’t be designed. It comes very natural to me and I feel this unique way of showing stories looks attractive to festivals. Though I can never be sure what made Mannheim-Heidelberg to invite my film, but this is my understanding. And I believe in making good films without any calculation. Making a film which connects with the heart of audiences is the most important thing for me and I try it with full honesty.

Widow of Silence has already won a lot of accolades such as the Best Film awards at Kolkata International Film Festival, MOOOV Festival, Belgium as well as Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles. How important are such awards in boosting the prospects of indie films?

Winning accolades certainly boosts a film’s visibility and acceptance. Due to the film’s dreamlike festival run — starting from the prestigious Busan International Film Festival, Rotterdam to almost now 30 reputed festivals worldwide, including some wins — has improved the film’s prospects of reaching out to audiences. Widow of Silence will be released commercially at theatres in Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg because it won the Best Film Award at MOOOV Festival in Belgium. Though in India it hardly makes a difference, as theatres here are more interested in earning footfalls and indie films do not fit into their business plan. Releasing films in theatres requires huge resources and most of the time true indie filmmakers don’t have such a luxury.

In your films you mostly like to work with non-actors. Why are you not comfortable working with professional actors? What prompted you to cast a known theatre actor like Shilpi Marwaha in the lead role in Widow of Silence?

I love the realism and rawness of non-actors which makes my films very believable. I think they make it very special. They help transport the audiences to the real world as they feel their pain and happiness, as if they are present at the place where the story is happening.

But despite my love for non-actors, sometimes I want to show some scenes in a very particular way which I feel will not have the same impact had I shot it any other way. For instance, in Widow of Silence, there is a very intense and emotional scene — which is almost four and half minutes long in which a mother and her daughter are talking in the middle of the night. They share their helplessness, desire, ambition and determination to overcome the impending bleak future. I wanted to shoot this scene in one long take without cut or change in camera position. I was very adamant shoot it in this way only. Probably for a non-actor such a long take would not have been very comfortable. I wanted a trained actor who could pull off this strong yet very subtle scene and so I opted for Shilpi.

You tend to rely on long takes, coupled with slow panning, in all your films. Why is the long take so important for you in the cinematic telling of the stories?

The primary reason for taking long takes is to not manipulate or direct the audience to see things in a certain way. Long takes help audience to see the scene the way they want to see, to search and feel and understand. It’s important for me to give space to my audience and their thought process, and to absorb what is being shown on screen. I want them to be a part of the film’s journey rather than just a spectator. Their involvement comes only when they have the freedom to choose.

Tell us about your collaboration with the Iranian cinematographer Mohammad Reza Jahanpanah.

I remember watching a film at a festival. It was one particular shot I liked in the film which Mohammad Reza Jahanpanah had shot earlier. That was the kind of visual imagination I had for the Walking with the Wind, which I was planning to start. I contacted Mr. Reza and within a few days he agreed.

I believe the kind of humanistic cinema I am making, for that the creative team must have the same level of emotional attachment to it. It’s not just about expertise in the craft. Such cinema demands much more human involvement and understanding. And cinematographer Mohammad Reza Jahanpanah is such a kind human being. His understanding and artistic approach to each character and scene greatly adds to the film. It has been a wonderful association. It’s always a great experience for all of us, filled with wonderful memories.

How was the experience of shooting the film in a remote town like Dras? Also, tell us about the challenges of working on small budget films.

The local people at Dras in Kashmir and the hospitality offered by them made the film possible. It was a difficult terrain and had a harsh weather, with hardly any facilities. Cinema anyway is never easy to make, so I never take hurdles and difficulty as challenges. As a filmmaker, I have to overcome these by only creative solutions. Thanks to my filmmaking experiences over the last few years, I have devised ways to use limited budget to create films.

Tell us about your upcoming projects.

I was about to start a new film this October in Kashmir, but due to the prevailing situation it is not possible to shoot. I hope to start it soon. As location is like an important character for me, I must shoot it in Kashmir only.