Hundreds of canteens and eateries serving the younger crowd have either downed shutters or shutting down. With little support from the government, this is leading to a loss of jobs and exodus of workers in the sector

Despite the mounting number of cases in the city, Covid-19 is not the only reason causing distress among people at large, and small businesses in particular. Pauperisation due to the loss of livelihood remains a potent existential threat in comparison to the pandemic.

The first exodus saw migrant labourers leaving the city. The next wave will be of people working petty jobs in the informal sector. Shutting down of canteens and small eateries, primarily meant for the younger folks, has resulted in insurmountable hardships. Some have tried to reopen and start home deliveries but the response, to put it mildly, is not very encouraging.

Sudesh Kerong Subba, 29, from Darjeeling, has been working in one of the many canteens near JNU along with a dozen of his friends. He was the last one to go back to Darjeeling last Sunday. “We were paid half a month’s salary in March. That’s it. Since then most of my friends have left Delhi. Some didn’t even have the money to pay for their tickets,” he recounts in a dejected tone.

“The situation is bad and the worst part is that there’s little hope of revival in the near future,” says Subba, who has vacated his room in Munirka and gone back to a tea garden near Darjeeling where his family works. At least, he’s happy to escape the Delhi heat. “There’s no way we could have sustained here in Delhi. I will only come back early next year if the situation gets better,” Subba is keeping his fingers crossed.

“Uncertainty is not an easy feeling,” he says, “How will the city run if all the working people go back to their villages?” he asks in Hindi.

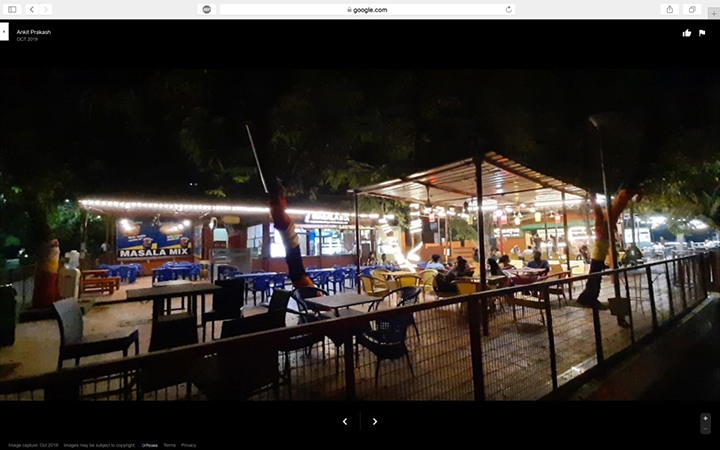

Most of the canteens in Delhi University, Jamia Milia Islamia, IIT, and JNU are shut because most of the students have gone back home. Akhilesh Motiwal runs a canteen on campus IIT Delhi, Massala Mix, a ten-minute walk away from the academic block. The IIT authorities have not allowed him to open Massala Mix. Motiwal informs that there are some 50 commercial establishments within the IIT campus allotted to people without due process of tendering and the staff of IIT is whimsically harassing some of them. While the preferred ones are allowed to operate, even awarded contracts to supply food to the security staff, and are even allowed to carry out home deliveries while others are prevented from operating.

Motiwal has taken the matter to court, which has stayed the eviction notice served to him, within just two years, despite his contract allowing him to operate for five. He was allotted an open space and subsequently spent Rs 35 lakhs to build his eatery. Over time, it became a popular joint with a daily footfall of around 1,000 people. However, after the lockdown was lifted, he wasn’t allowed to open. After he petitioned the top authorities at the IIT, he was given permission to operate on the condition that he’ll meet SOP requirements. “It has been a month, and SOP approval has not been given,” Motiwal says, “and I’m harassed by the IIT security staff.”

He has a fixed cost of Rs 2.5 lakh a month, plus has to pay taxes, also the salary of the staff. His prized chefs need to be paid or else they will join some other place. Out of desperation, he shifted some of the equipment to his residence in South Delhi–not far from IIT–sent some 10,000 WhatsApp messages informing that Massala Mix is open and ready for home delivery. “The response has been bad, hardly 10 orders a day. People don’t want to take chances, students have left hostels and rented accommodation or gone back home and people, now confined to their homes, have all the time to prepare food,” he reasons as to why things are unlikely to improve. “It’s a battle of survival and an arduous one. Government and its institutions, instead of supporting, have made life difficult for petty entrepreneurs,” he adds.

Multinational chains, because of the clout they enjoy, are making gains due to their already well-established home delivery system. “While Massala Mix is not allowed to make home deliveries, Swiggy and such services are allowed in IIT,” points out Motiwal. Many canteen owners have similar problems and have to deal with the high-handedness of the authorities in times of a pandemic.

Vicky Mandal, 25, was a consultant for setting up of eateries for five years when he decided to start a venture of his own last year. The idea was to provide younger people with experiential bonanza along with the food, hence the name Altogether Experimental, located in Saidulajab, near the IGNOU university. The area also home to many coaching centres ensures a ready supply of younger folks.

Altogether Experimental doesn’t fit into the stereotypical description of a cafe or restaurant, canteen, or a bar. Vicky along with his partner Anukriti Anand, employed all their resources, took loans, to have the place up and running. Vicky employs phrases like “radical coffee making techniques, avant-garde food, contemporary sustainable architecture, large open spaces” to describe his dream project and explains, “We operate in an ecologically friendly way and make sure no ingredient is wasted.” The going was good when all hell broke loose, thanks to the pandemic.

They remained shut for two months. Out of the 15 employees, only six remain. The Experiential Engagement, an eatery, their USP, is now not even a consideration. To sustain the project, for the last month or so they are trying to work through home deliveries. “The response is better now,” says Vicky but not good enough.

Delhi is known for its varied cuisines, it is a paradise for foodies and connoisseurs alike. There’s food available that suits all pockets. Street food joints, canteens, dhabha feeds the poor and is a source of livelihood for lakhs of people. A city that can’t feed its people is not a happy place.