Hailing from Bihar means living with a stereotypical image – that one must be dark, speak poor English and don’t deserve outstanding success

The death in Mumbai last week feels like I could have been that person. Shining star and all. Introverted, intense, quiet, mind buzzing with a million photons a second. No patience for small talk, lobbies, networks. No friends for benefits, a world of one’s own, dreams to follow, hearts to please, world to make better. Idealism and identity, one complementing the other. No part of us to sell, no part of others to buy. Values over money, dreams over destination.

I have scanned every possible media report on the death and watched countless videos. I am struck by the revelation his death has brought, an important detail he carefully avoided mentioning in his interviews for years: he was born and raised in Patna, the capital of my home state Bihar. Now, reports say he remained an outsider; he was never accepted; his good work little acknowledged in an industry where nepotism thrives and where an influential surname trumps hard work and talent. Exceptions exist but exceptions don’t make the rule.

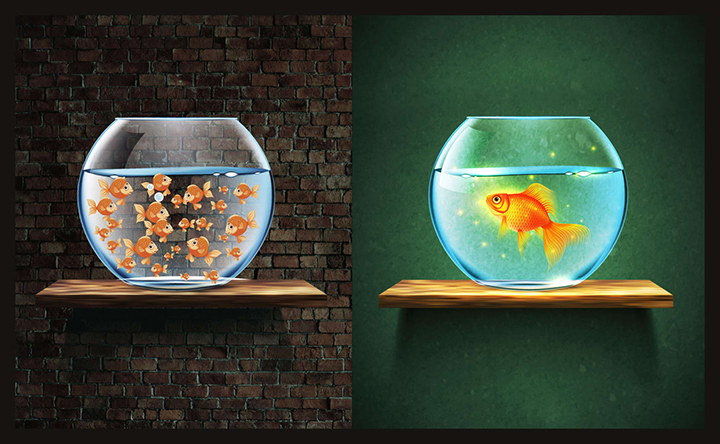

I am regressing into the past, to the place where education is the widely accepted route for intergenerational mobility, for a career, for social prestige, for an escape from poverty. So, the middleclass boy from Patna started off excelling at academics, eventually to realise that he loved to act. Years of struggle in theatre, television and finally, fledgling stardom in a deeply unequal industry. Sure, others have been there too – like a unitary flicker in a deep dungeon that blocks out redeeming rays of opportunities.

Haven’t we all been naïve to equate getting an education with fairness, equal opportunity and acceptance? So what if we are bright and can work hard to get what must rightfully belong to us? Some things are still defined by our roots, by the selfish decisions made by people we vote to power, by the poverty and absence of enterprise that stifle our dreams but must continue to define us even if we run away from it the first chance we get.

What I mean is that sometimes the casual inference drawn from contexts we cannot shed nor are we responsible for, can continue to define us. Worse, we no longer know what or who we are. We alternate between days when we hear the yearning within us to burn the premediated paths and arise out of our circumstances to dazzle, and then, days when we allow the unfair prejudices and perceptions to overwhelm us.

We no longer remain the person we are and we see the world crashing around us. We allow others’ negativity to swallow our voice, so much so that when we speak, we hear them, not ourselves or the people who believe in us. We hear outsiders way too much and that one day eliminates us. Death is never a sudden event; it proceeds like the supersonic wave on a long holiday that we can’t hear and cannot escape. Our courage or our burning ambition, nothing matters when the other voices, outside of us, become our master.

Creativity is the measure of beauty humans can create, but it’s also a curse. The world may not be kind to our craft, instil doubt instead of inspiration, and that’s the beginning of disbelief in oneself. When I started writing, first in school and later as a journalist, I remained a closet storyteller, unsure of every word I wrote. I didn’t build an echo chamber where I could exchange favours. Writing was art, straight from the heart, not a commodity to be sold or traded in barter.

Appreciation is a cruel social construct. Once we accept its influence, we are doomed for disaster. Yet, the heart craves it and works to turn its infidel gaze in its favour. Some defy, rejection or no rejection, like SSR, and it may not end well. Perhaps, art in some form resists it because it fears its corrupting influence, its disrespect for the craft, its pandering to the norms, its opaque standards. Our resolve to stick to our art alone can break us. To watch that happening can break those who watch.

I am breaking apart too, as I revisit the past and tie its cruel reminders to the pain in the present. Biharis, the small town people, are the George Floyds of India, but we continue to bear indifference or ridicule and carry on as if none of this exists. I have, for years. Many do.

Meritocracy can take the same plea but that has lost fervour in a world of deepening inequalities. Being poor or deprived draws attention, but not all of us fit into the frame they consider important to their activism. Sometimes, not being poor or deprived becomes our nemesis, our invisibility, deliberate erasing of our struggles.

In the past few weeks, one could argue, millions of Indians have raged and agitated for millions of Biharis. I know. Millions of them were fed, given tickets or interviewed to draw out their miseries, sometimes with tears, sometimes with fear. I don’t undermine any of this. I have also read reports of millions of migrant workers from Bihar sparking a conversation on privilege.

But death of a bright spark amongst us — a successful migrant in India’s city of dreams, someone who challenged the status quo and unearned stardom of several newcomers with lots left to prove — doesn’t elicit the same response a walking crowd of migrants did. The scale of misery and deprivation are different, I know. A little push to uplift the already fallen doesn’t threaten anything but reduces the burden of guilt enormously – a mountain cleared from the conscience of the rich and the privileged.

Even as I write this, must I feel shame that I am pointing at this as if no good was done, that I am reeking of privilege or ignorance or bitterness in comparing the two, and that I should be drowning in gratitude instead. Oh, but today, I must, without worrying too much about what others make of it.

When we are teenagers in Bihar and we ask for space or demand to be heard, those who hold power over our situation pat on our back, saying, “Bahut chatpatiya bachcha hai. Seekh jaayega (The child is restless, will learn with time)!” We learn to learn the way we are expected to, or we snap out, rudderless. We swimmingly endeavour to survive, we build a wall to protect ourselves, we smile excessively to shield our pride from breaking.

In everything exposed to risk in combat, pride is what people who leave home for better futures protect. Pride represents sovereign choice, the freedom to make mistakes and claim them as learnings, to reject cages, to fight adversity, to draw from our roots to craft our wings and fly. Yet, the roots that we so need to flower — where it takes us and what it does isn’t the choice we can make. We can choose to discard it, many do, but the abdication of identity is never final. Culture is like flavour – it seeps in and defines the taste of satisfaction, belonging, fulfilment. We couldn’t let go even if we wanted. Living with it is not peaceful either. For the George Floyd in us, there is no revolution waiting.

I arrived in Chennai, the southern Indian city once known as Madras, and it felt like the first shelter you run into on a sultry May afternoon after one escapes from Patna. In the flat I am sharing with three other girls as part of the residential programme that would prepare me for journalism, the girls tell me they are from Bangalore, Trivandrum and Calcutta, cities I have only read about in magazines.

I settle down but the milieu around me is reasonably stirred. They don’t expect someone like me to get in, but I have. I don’t get the barbs they casually throw at me. I don’t eavesdrop but I can sense that they whisper when I am in the bedroom. Sometimes, on television, the girls from Bangalore and Trivandrum bond over South Indian cinema and crack jokes in Malayalam or Telugu but this is definitely not Hindi or English, languages I understand. The girl from Kolkata is often on the phone chatting.

I stay away in my room, reading. Sometimes, I escape to a small bunch of girls from Faridabad and Agra who stay on the floor above. They both unfailingly mention they studied at Delhi University, but they love me fiercely, I realise over time, and call me the “girl with nerves of steel”. I don’t know if I am worthy of this moniker but I take it that hailing from Patna and finding myself to be strong, ambitious and striving for a career must be courageous, something few expect us to be.

This is what defines underdogs, I convince myself. The admission panel during the college entrance told me, my test paper score was amongst the top performances of my batch. In Bihar, academic excellence is not a badge to wear everywhere; it’s a necessity or we will be doomed. We don’t brag about doing well because where will we be if we don’t! So I never mention it, not even casually. This detail is folded away like a secret in favour of listening to the languages I don’t have to learn, stories I am told but can never tell because no one asks, and the countless judgements that jolt me out of the cocooned, aristocratic upbringing I have had in my home state overnight.

In this new world where I have come to seek equal opportunities, I am an outsider, the odd one out in this tight-fisted fabric of regional privilege that allows no diversity, not a flicker of difference it can respect.

“You don’t look or speak like a Bihari. You sound more like someone from Bombay!” A classmate remarks within weeks of my arrival as we head to the juice shop on Mount Road where she often attributes my pink cheeks to the orange juice I have been drinking everyday as afternoon snack. I internally scream: I was born with apple-red cheeks!

But to the many worlds that exist within a country of India’s diverse scale, people from my world are impoverished, dark, and to suit their narrative, always pale, their molars protruding like salivating tongues of hungry dogs. We just don’t do any better, wherever we go, whatever we do. Brightness and brilliance belong in the other worlds.

My flatmate from Kolkata cannot believe my father decides on matters of life and death in a court of law, my mother teaches science at university, and I have grown up playing cricket with boys. So, she draws me into debates, in the bedroom we share, or sometimes, near the swimming pool of our high-end college residential accommodation where I often go in the evenings to be left alone with my thoughts. She doesn’t miss a chance to probe me on politics, literature and law, just to fathom how deep I can go, or how shallow! She attacks me on once in the online yahoo group for our batch deriding me for my culture.

Those who have been hanging out with me counter, but in “private messages” condemning her outburst. No condemnation publicly. No courage in this world, not a whimper, not even humanity for someone they have secretly, unilaterally declared an outcast. My hands refresh the mail browser all day as the caustic words in her email float on my screen, waiting for one nod to the pain I am experiencing, the alienation I feel, the hatred I have been subjected to. There is no mention, nothing at all, of the racist onslaught that has passed as casual slug fest. The mail I want never comes. I hold on to the response I have feverishly typed and in the evening, I save this as draft never to open again. “I don’t care and I don’t want to respond to the ugliness,” I tell a friend trying to sound cool even as my heart smoulders in scalding flames of humiliation and rage.

When I arrived in Chennai for the first time, I realised people like me have to travel outside of our state to contest the million perceptions hurled at us. The severity of it may vary and take less brutal forms, but the judgement never really stops. In the years since, I have moved cities — from Mumbai to New Delhi to London — but the prism of prejudice stays where it was that year in Chennai. Over the years, I have heard “Bihari” used as an abuse to describe people with less education or manners, and worse, and not just in circles of privilege.

I am not saying this discrimination is exclusive to Biharis alone, but Bihar is always seen as the poor country cousin who gets relegated to toiling in the fields as low-paid labour, in the factories in India’s metros, in households, everywhere. Bihar is not just poor, it is also overwhelmingly backward — more than 70% of its population belongs to backward/scheduled classes or castes. India’s diversity and its ethnicities make a bloody cauldron where discrimination on the basis of caste or region is rampant. Everyday conversations can do the job – their ignorance becomes their excuse to bully, their judgement becomes their conviction, and their twisted, half-baked view of the world becomes the last word in conversations. Many conform to this matrix of social exchanges, change or silence themselves to fit in, and eventually dissolve into the metropolitan smoke that engulfs all differences and makes our non-conformist sliver merge into their asphyxiating norm.

If we don’t, we aren’t welcome; they don’t care about us except when they want to talk about development and poverty for a change. Hang in there, some of them say, before vanishing into their world never to turn back. This is their world and we are never welcome unless we change the way we speak, the words we claim as indigenous to us, the colour of our skin (not always dark as they imagine!), our freedom to be without inviting their disdain, pity or ridicule.

Our place and caste at birth aren’t the choices we make. We realise this as soon as we step outside of our comfort zone, our homes, our circles of joy. We either begin to hide or we invent answers that may lie somewhere between fact and fiction. Or, we claim it all as an act of defiance. We could change religion to overcome caste; we could migrate and change the city in our passports. We learn to appreciate diversity while accepting that we wouldn’t speak our mother tongue without suffering the humiliation of raised eyebrows.

What’s left of identity leaves us – words, pronunciation, slang, manner of conversations and socialising, the love for mother’s food, father’s woollen monkey cap, our festivals, songs, and cinema. Our cultural capitulation rewards us with patronising praise; it opens doors. Our silence or indifference earns us alienation, a cold shower of invisibility that would bury us if we weren’t good. But sometimes, being good is not enough.

Must what we achieve depend only on the choices and efforts we make or be predetermined by factors beyond our control? This is not an easy question. For decades, thinkers, philosophers and policymakers have debated this and generally agreed that the returns to efforts made by individuals of different family backgrounds and regions were different.

In the United States, Europe or Asia, various studies now define the definitive new agenda on the role of one’s family background or place of birth in the overall achievement of an individual, be it earnings or cognitive ability or social mobility. One could be a cog in the wheel with roots in disadvantaged ethnic communities. This could lead to lower earnings, low intergenerational mobility, long term poverty, stunted access to opportunities and countless other inequalities. From dwindling social justice and stunted inclusive growth, pervasive inequalities of opportunity arise.

In India, this gets worse. Caught in the muddle of caste, region, religion and languages, we fight discrimination until we die or fail. Inequalities based on caste and ethnicity leading to unfair perceptions and prejudices — these haunt us until we adjust, make peace or get lucky. We need policy interventions because this discrimination leads to social exclusion and violation of civil rights. Superior social status ascribed to people at birth and the incalculable privileges that come with it accentuate the historical divide and spawn new inequalities. This misery is deadly at all levels. Imagine yourself dying because someone sabotaged your business idea or your movie project or your promotion at work simply because they don’t like where you come from. This happens — the “deaths of despair”, to borrow the title of Nobel laureate Angus Deaton’s recent book — and you couldn’t dismiss failures arising out of these as mere clinical depression.

Those with overarching interest in tracking ethnicities and forming perceptions can start with tracing roots of depression that lead people to do the unthinkable. The calibrated putting out of talent to honour the glory of averages – this inequality of opportunity may not be visible to the naked eye or decipherable in an economist’s paper but it affects outsiders everywhere, across industries, across income groups. They will find living easier than dying only when the knowledge that discrimination and prejudice are not acceptable becomes the defining ache of India’s collective conscience.

(Cover: Illustration by Parag Dabke for EconHistorienne)