As innocent kids, we brought back home a brick from the demolished mosque. Now, I remember the agony both communities suffered

Disclaimer: The author is associated with the Indian National Congress.

In 1989, I was five when, for the first time, I went to the Ram Temple which resided inside the Babri Mosque. This was after the opening of the Ram temple lock and the first bhumi pujan. I remember seeing the shilanyas, or foundation stone, placed near the mosque.

In 1990, Mulayam Singh Yadav’s government ordered firing at karsevaks, the devotees who came chanting “Ram Lala ham aayenge mandir wahi banayenge”. In turn, he became the “ladala” (beloved) of Muslims. While my mother was in a hospital treating people who got injured, I was home alone, hurling abuses at a helicopter (believed to be ferrying the chief minister), as everyone else around did, calling him “Mulla Mulayam”. Curfew had been imposed but as innocent kids, we clapped from our rooftop at the sight of smoke from a burning police station nearby.

Later when the curfew was lifted, my mother took us to the hospital where we went to the mortuary to see the men killed in police firing (referred to as “martyrs” by Hindus). The firing on October 30 and November 2, 1990 killed 16 people, including Ramesh Pandey, a local and father of a boy who would later be my classmate. Pandey’s wife was also an acquaintance and came to our home a few times. We also heard stories of a sadhu who got hold of a government bus and ramped open many barricades that allowed the Kothari brothers to climb over the Babri Mosque and hoist the bhagwa flag.

We then went to see the bullet marks in the “shaheed lane” where the police fired on the Kothari brothers and many others. When it all paused, everyone heaved a sigh of relief, especially the miniscule population of Muslims in Ayodhya.

In 1992, when I was eight, another surge of “ek dhakka aur do, Babri Masjid tod do” started. This time, conditions were favourable to the people involved in the movement as the Bharatiya Janata Party had control over the state machinery under then chief minister Kalyan Singh. The Supreme Court allowed another “karseva” after a written affidavit of the Uttar Pradesh government that it would not allow any harm to fall on the disputed structure. Atal Bihari Vajpayee delivered one of his few communal speeches: “Nukeele patthar hain, zameen ko samtal karna padega.” (Sharp stones are emerging from the ground. The ground will have to be levelled.)

On December 6, 1992, I was in the hospital with my mother and we saw the first karsevak rushing in on a stretcher and proclaiming “Jai Shri Ram”. He had slipped and broken his leg in an attempt to climb the mosque. Everyone feared another bloodbath but we soon got the news that the first dome was down and only those who fell in an attempt to demolish the structure were coming for treatment. The injured lauded the administration for their “support”.

Then we heard the news of another dome being demolished and then, finally, that the zameen is samtal now. Everyone around was jubilant. The emergency ward where injured were being treated had a ward boy who was diligently performing his duty. His name was Jaki Mohammad. He became Jacky for that week to conceal his identity and kept serving the “Ram sevaks”.

The next morning, my brother and I went to see the temple construction work in progress but within 15 minutes of reaching there, the Central Reserve Police Force took charge of the place and did some light lathi-charging. We ran just in time, through known lanes to our home, but that didn’t deter us from bringing back a brick from the demolished mosque.

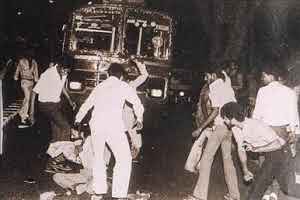

The celebration was soon over. Riots in many parts of the country had started. Dawood Ibrahim was soon going to resort to terrorism and India was going to witness her first brush with Islamic terrorism outside Kashmir. Jinnah’s hostage theory was being brought to practice and around 50 Hindu temples were either burned or bulldozed in Pakistan and Bangladesh. The persecution and killing of Hindus in these countries also increased since then.

The Ram sevaks still in Ayodhya thought it apt to teach the Muslims a lesson. As an eight-year-old boy, I saw them vandalise a mosque just outside my colony and burn houses of Muslims, including our Naaun (a Muslim barber lady who was as important as our panditji on any auspicious occasion, and somehow it never mattered that she was a Muslim). I then saw some locals looting these houses for some easy cash and assets.

A day later, I saw the police firing in the air and chasing some karsevaks through our lane because this time, the karsevaks tried to burn some Muslim houses on the other side of our colony. Luckily, the police reached on time. Once it all got over, we again heard stories, this time of some Muslims being burnt alive and some Hindus who tried to prevent this being thrashed. We also heard stories of how the local communities saved each other from outsiders.

Masterji’s tailoring shop was also burnt and so was my school, as that was owned by a Muslim. I then decided to shift to a school that people would never get to burn, the Saraswati Shishu Mandir run by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.

Interestingly, the “Ganga-Jamuni” culture of Ayodhya survived. The Naaun was back in our homes, we went to the Masterji who stitched our clothes, the rusk of Modern Bakery was once again served with tea. Though the change of school meant that I never met Ali, who always wore these fancy jackets that his father got from the Gulf, everything else gradually became normal. People laughed together, dined together, and did business together.

As I grew up and saw the world and got exposed to new things, I saw the misery of our minds. I could see the exploitation of religion and sentiments for power and politics. I could see the complaints that Masterji, Jaki Mohammad and our Naaun had in their eyes. I could see the pain and trauma these people were undergoing. I could see the hesitation the communities developed after the Babri demolition.

These heartbreaks and hesitation stayed with me. Whenever someone asked me, “When will the Ram temple be constructed”, I felt pained. It reminded me of the agony both the communities had suffered. It made me live those memories all over again. I hope from today, they won’t ask me this question anymore because I still don’t know if I should tell them what they want to hear, or what I want them to know.

www.newslaundry.com

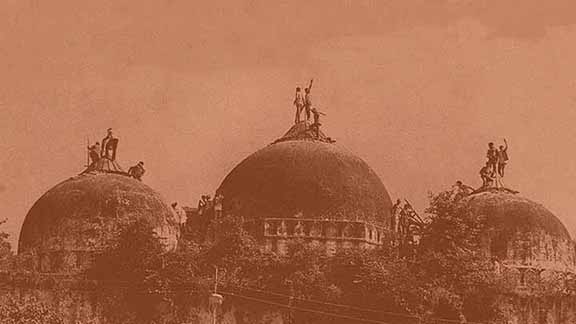

(Cover: On 6 December 1992, the disputed structure of Babri Masjid was brought down by a large group of activists of the Vishva Hindu Parishad // Photo: newslaundry.com)