Amidst the rising number of Coronavirus cases in the country, Muslims in India celebrated Eid-ul Adha while trying stick to the government guidelines which often differed from state to state

As the Coronavirus pandemic keeps unfolding, the very definition of a normal life has been changing. For as long as there is no viable treatment or vaccinations for the virus, there will be firsts in the way we socialise, the way we work and the way we celebrate festivals. One such first was on 1 August, the day when Eid-ul-Adha was celebrated in the country.

For those who may be unaware, Eid-ul-Adha, popularly known as Bakr-id is celebrated roughly two months after Eid-ul-fitr and marks the end of the performance of the rituals of Haj with the subsequent sacrifice of animals. For Muslims across the world, this then is one of the two most important festivals of the year.

Coming from a Muslim family based in Lucknow, I have since childhood looked forward to the festival, not only because of the customary siwai and sheer after a scrumptious meal of kebabs and biryani but also because of the opportunity of exploring the old city in search of goats and sheep for the sacrifice.

As has been the case with life since March, special directives from the government of Uttar Pradesh regarding the celebration of the festival dictated protocols to ensure the virus does not spread during the festival. These directives included not allowing mass prayers in mosques, not allowing transportation of meat and animals, and not allowing any temporary animal markets to operate. And though these measures, barring ones that disallowed the transportation of meat and animals, seemed to have put in place to contain the spread of the virus, they sure did change the way we usually celebrate Eid.

For starters, the customary stroll on the streets of the old city, where hundreds of shepherds would gather to sell goats was obviously missing. And with their absence, the pleasure of a cup of Kashmiri chai in hand while haggling with the shepherds in the vicinity of the magnificent Rumi Darwaza were dashed.

They were instead replaced with rumours that those shepherds who did come to the city to clinch sales were being asked to bribe officials, all the while being under the constant threat of being beaten up by the police. These rumours further found takers when requests to allow mass prayers in mosques under guarantee of adherence to social distancing norms were denied by the authorities, even though similar requests were approved by Central and other State governments.

The directives prohibiting the transport of animals and meat was another contentious issue, as people who could afford to purchase animals from outside the city did not want to get into trouble at the state borders. The consensus then was to sacrifice whatever goats one could purchase close to their houses and avoid going against the directives. Adding to the woes of the people, especially the shepherds and butchers who wait for this Eid all year round for the economic opportunity it presents them, was that 1 August was a Saturday, and Uttar Pradesh has a state-imposed weekend lockdown. As per the lockdown rules, no businesses apert from essentials, factories and IT companies were allowed to function.

On the morning of Eid, due to close family ties with the Imam of the neighbourhood mosque, we were able to perform the namaaz within the confines of our home. Even then, masks and distancing norms were kept in mind while interacting with the imam. The customary hugging and shaking of hands gave way to nods and salaams and this trend kept up for the next three days—the number of days qurbani is performed.

Having a small farmhouse close to the city limits, we were able to purchase and keep goats for sacrifice there till the day of Eid, when they were brought over to the house for sacrificing. But even when performing the sacrifice, there were a number of things that had changed. For starters, we asked the butchers not to remove their masks and to sanitise their gloves once they entered the house. Similarly, everyone who came to receive their share of the sacrificial animal’s meat—the meat of the animal being sacrificed has to be divided into three equal parts, one for the family performing the sacrifice, one for their neighbours and relatives and one for the economically weaker sections — had to first sanitise their shoes and hands and face masks had to be worn at all times. The method of wishing Eid Mubarak was also the same as it was in the morning: nods and salaams.

When it came to distributing the shares from the sacrifice, we waited till Monday to be able to do so. Even then, many people were apprehensive about carrying even small quantities of meat on their motorcycles and even in their cars. The problem became even more acute when meat had to be transported to madrassas and orphanages for distribution and preparation of food. However, despite all odds, things were managed and rituals were performed smoothly. And with the relaxing of lockdown norms on the second day of Eid, Sunday — with the upcoming festival of Rakshabandhan on Monday– things became even easier.

Even though the Coronavirus has changed the way we normally celebrate festivals and socialise, it can be done without endangering exposure to the virus. However, a lack of precise and comprehensible guidelines from the government that could make things easier for the people could be felt. In any case, celebrating festivals under the new normal is possible as long we take care to follow social distancing and proper sanitisation.

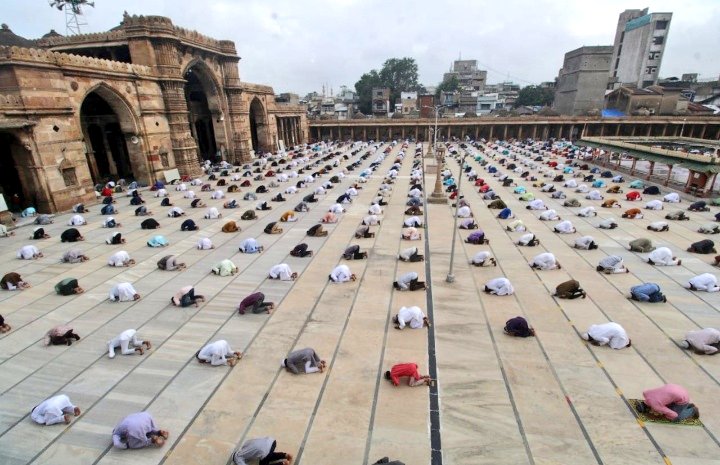

(Cover: Prayers were offered at mosques in India while adhering to social distancing // Photo: Twitter.com)