Since people these days don’t trust the mainstream media much, they end up trusting a lot of nonsense that appears on social media

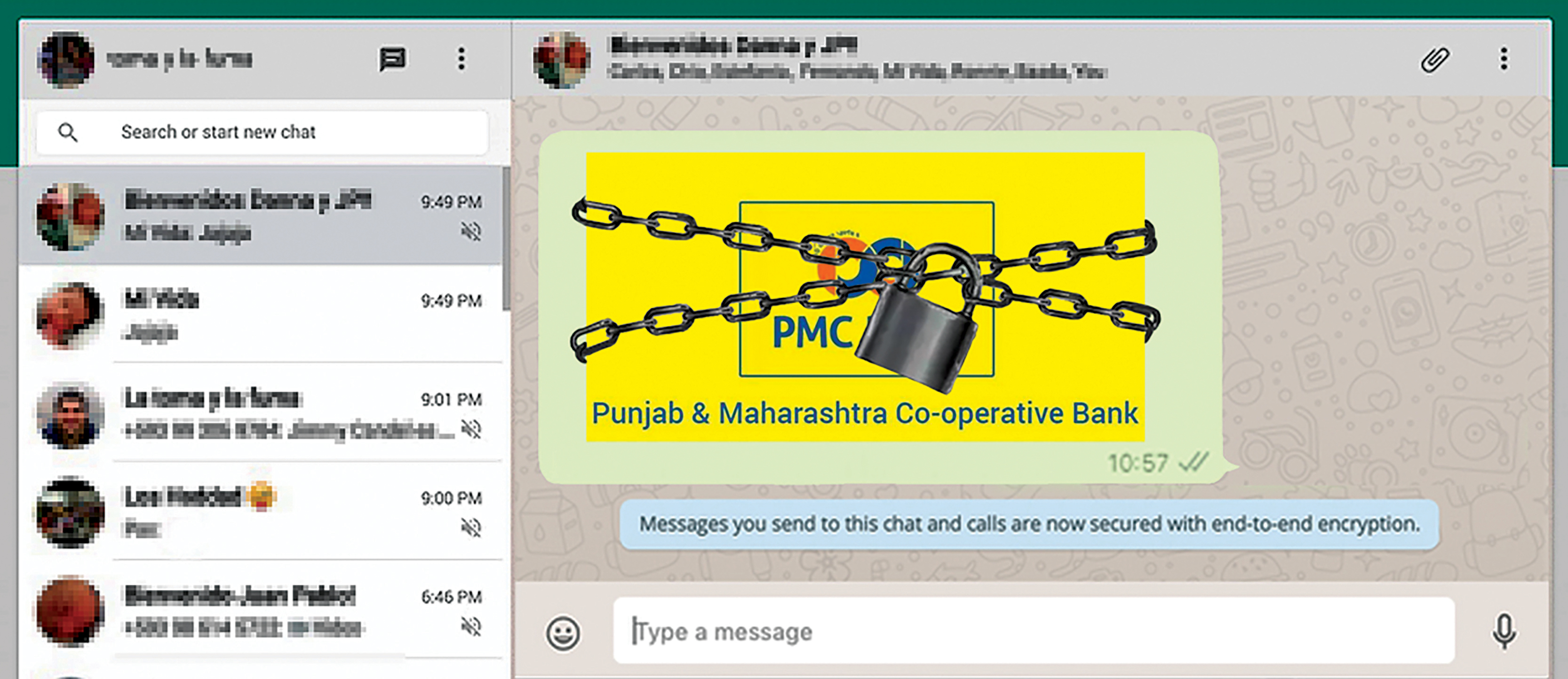

On September 24, 2019, the Reserve Bank of India put operational restrictions on the Punjab and Maharashtra Cooperative Bank. This urban cooperative bank operates primarily in Maharashtra but, despite the name, doesn’t have a single branch in Punjab. The RBI limited withdrawals from the bank to Rs 1,000, before increasing it to Rs 50,000.

Within hours of the RBI limiting withdrawals, the news was all over mainstream and social media. One message that went viral on WhatsApp was that after the PMC Bank, the RBI and the government planned to shut down not one, not two, not three, but nine public sector banks.

My first response to the message was, “Why would anyone in their right mind believe it?” Why would any government and/or the RBI shut down nine public sector banks at the same time and risk creating social tension in large parts of the country?

But such was the virality of the message, for lack of a better term, that even the RBI had to put out a press release on Twitter pointing out that no such plan was on the anvil.

Why did I feel the message was ridiculous and totally false? First, the RBI does not have the power to shut down a public sector bank. Of course, it is a technical point and not many people would know.

One bank on the list was Dena Bank, which had already been merged with the Bank of Baroda. Another was Corporation Bank, which is being merged with the Union Bank of India. So, we had a bank which had ceased to exist and another that would cease to exist. How could these banks be shut down?

Soon, videos of bank depositors were going around on WhatsApp. One video that I remember well had a schoolteacher who had put her life savings in the PMC Bank and had no access to the money. Another news item that went viral was about a depositor who died of cardiac arrest after he couldn’t withdraw money for an operation.

All this has created a sense of panic among depositors across the country.

In fact, I recently did a video podcast with Akash Banerjee, who goes by the name of @TheDeshBhakt on social media, and we asked for questions on social media before the recording. The maximum number of questions we got were on the safety of bank deposits.

In late 2017 and early 2018, after the Narendra Modi government introduced the Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance Bill of 2017 in the parliament, people received lots of WhatsApp messages essentially saying the government was planning to use their bank deposits to rescue all the banks that were in trouble. This created a financial panic.

WhatsApp and other social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook have been used to create a perception that bank deposits are unsafe. How is this happening? Let’s look at it pointwise.

1) Producing fake news is cheap. All it requires is a literate person who is largely idle and has a mobile phone with an internet connection. The same is not true for news produced by the media which at least up until a few years back used to cost a lot of money.

As Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo write in their new book, Good Economics for Hard Times: “Circulation of news on social media is killing the production of reliable news and analysis. Producing fake news is of course very cheap and very rewarding economically since, unconstrained by reality, it is easy to serve to your readership exactly what they want to read. But if you don’t want to make things up, you can also just copy it from elsewhere. A study found that 55 percent of the content diffused by news sites and media in France is almost entirely cut and pasted, but the source is only mentioned in less than five percent of cases.”

The larger point here, as Banerjee and Duflo put it, is “the economic model that sustained journalism as a location for “pubic space” (and correct information) is collapsing”. In this scenario, “without access to proper facts, it is easier to indulge in nonsense”.

The rise of Twitter and WhatsApp has come at the cost of people’s belief going down in what used to be the conventional media. Of course, the rise of Twitter and Facebook isn’t the only reason for this. Given that people don’t trust the media much, they end up trusting a lot of nonsense that gets sent over on WhatsApp.

2) Let’s go back to the example of the WhatsApp message that said the government and the RBI were planning to shut down nine public sector banks. Why did people believe it, without even doing some basic factchecking?

As Robert J Shiller writes in Narrative Economics: “The human mind seems to have a built-in interest in conspiracies, a tendency to form a personal identity and a loyalty to friends based on the desire to protect oneself from the perceived plots of others.”

People had seen the state of the depositors of PMC Bank on social media. Hence, there was a desire to protect their deposits in public sector banks, from a perceived plot by the RBI to shutdown these banks. In this scenario, it didn’t matter for most people whether the piece of news about the RBI shutting down banks was true or not.

Of course, this does not mean that everyone bought the fake news. There would definitely be people who realised it was fake news but still ended up forwarding the message. Why did this happen? As Shiller writes: “People are more likely to share novel information. In other words, contagion reflects the urge to titillate and surprise others.” Even if a news story is patently false, and the person forwarding it knows its false, he or she might still forward it just to surprise others. One forward that I get every year from highly educated relatives is about how fish are flying in the air in Mumbai.

This is something that happened in case of the PMC Bank as well. As Shiller writes: “‘Fake news is not new. In fact, people have always liked amusing stories and they spread stories that they suspect are not true…In other words, at some level, many people enjoy believing the story and do not care about its factuality.” This just adds to the panic.

Further, even if a new story correcting the false story is published, as tends to be the case with so many fact-checking sites now in vogue, the new story may not be as contagious as the false story. This means there will be people out there who will continue to believe the false story, just because someone sent it to them on WhatsApp.

3) Social media has the capacity for endless repetition or what is known as an echo chamber. This is what political parties all over the world try to make use of, by feeding content that their supporters like to believe in and creating hatred towards a class or community or caste or religion.

Nevertheless, this characteristic of the social media creates a problem in case of false forwards in the areas of economics and finance. As Banerjee and Duflo write, “The problem with echo chambers is not just that we are only exposed to ideas we like; we are also exposed to them again and again and again, endlessly.”

This is primarily what happened in case of the PMC Bank as well as after the FRDI Bill was introduced in Parliament. I got the message regarding the RBI and the government planning to shut down public sector banks, from many different people. I might be slightly more informed about these things than an average Indian. But imagine what would be going on in the mind of a person who got this particular WhatsApp message over and over again.

The fact that many different people sent the same false message to him might have led him to believe that the government actually had such a plan and the money in bank was actually unsafe.

4) Let’s take the case of Mukesh Harane, who died of oral cancer in October 2009. He was addicted to gutka. After his death he became the face of the anti-tobacco message which was delivered to the people of this country through an audio-visual clip (shown regularly in cinema halls) as well as a print campaign. Why I am talking about him will soon become clear.

The makers of the message were trying to play on the concept of an identifiable victim.

Who is an identifiable victim? Thomas Schelling writes in Choice and Consequence: Perspectives of an Errant Economist, “Let a six-year-old girl with brown hair need thousands of dollars for an operation that will prolong her life until Christmas, and the post office will be swamped with nickels and dimes to save her. But let it be reported that without a sales tax the hospital facilities of Massa-chusetts will deteriorate and cause a barely perceptible increase in preventable deaths – not many will drop a tear or reach for their checkbooks.”

Schelling came up with this example of a six-year-old girl to essentially distinguish between a “statistical life” and an “identified life”. The sick girl dying is an identified life whereas the people dying in hospitals are “merely” statistical lives because we do not know who they are. Hence, people are ready to donate money in order to save an identified life, but do nothing about the statistical one.

Along similar lines, the team which made the anti-tobacco campaign could have simply said so many people die every year because of consuming tobacco. Or they could have talked about the ill-effects of consuming tobacco. But that wouldn’t have had the same impact in the minds of people that featuring Mukesh eventually did.

As the Nobel Prize winning economist Jean Tirole writes in Economics for the Common Good: “We feel greater empathy when we identify with victims, and to do so it helps if we can recognise them. Psychologists have identified our tendency to attach more importance to people whose faces we know than to other anonymous people.”

Take the case of the distressing picture of a three-year-old Syrian child, Aylan Kurdi, who was found dead on a Turkish beach in 2015. This forced Europe to pay attention to the refugees coming in from Syria. As Tirole writes: “It had much more impact on Europeans’ awareness than the statistics about thousands of migrants who had already drowned in the Mediterranean…A single identifiable victim may effect many more minds than millions of anonymous victims.”

What’s the point I am trying to make? When videos of the victims of operational restrictions being put on the PMC Bank started to go around, this is exactly what happened. Without videos going around, the general public would have just come to know that many people now don’t have access to their deposits. These people who did not have access to deposits anymore would be statistical lives. But the moment videos of victims started to go around, people could see an identifiable victim.

And when they saw an identifiable victim go through what he or she was, the immediate thought was this could happen to me as well. This further accentuated the feeling that bank deposits were unsafe.

5) Air travel is by far the safest mode of travel, though it may seem to be otherwise to many people. But why does travelling by air seem so unsafe? The answer lies in the fact that every air crash gets reported in the media. But all the safe landings that happen every day simply don’t make it to the news at all.

As Hans Rosling, along with Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Rönnlund, write in the Factfulness: “In 2016, a total of 40 million commercial passenger flights landed safely at their destinations. Only ten ended in fatal accidents. Of course, those were the ones the journalists wrote about: 0.000025 percent of the total. Safe flights are not newsworthy.”

How is this linked to what I am trying to communicate? For every video you see of a PMC Bank depositor who does not have access to all his or her deposits, there are millions of other depositors who continue to have access to their deposits and they continue to withdraw them as and when they feel like. But, of course, they are not making any videos to say so. And that’s because continuing to have access to deposits doesn’t make for news. Not having access makes for news.

6) The human mind needs simple information. As Sanjoy Chakrovorty writes in The Truth About Us: “Simple information…makes it possible for experts and non-experts to make sense of the overwhelming quantity of data that has to be processed by the human senses. The human brain has limited data-processing capacity and works best when it does not have to process new or too much information all the time; that is, when it can slot all or most incoming data into pre-existing categories in the mind. The preference for simple information is universal.”

Now how does this apply in the case of WhatsApp and the unsafeness of bank deposits? The deposit insurance available on bank deposits is Rs 1 lakh. This hasn’t changed since 1993. Quite a lot of people believe that all bank deposits are guaranteed by the government. They aren’t. Still others have now started to believe that in case of a bank ending up in trouble, they will get back only Rs 1 lakh. Technically, that is true. But that is not going to happen. Typically, any bank in trouble is rescued and merged with a stronger bank. In the past, the Global Trust Bank, which had run into trouble, was merged into the Oriental Bank of Commerce whereas the New Bank of India was merged with the Punjab National Bank.

Also, the government rescues public sector banks every year, just that it doesn’t say so. In the last two years, the government has invested Rs 1.96 lakh crore to keep these banks going. This year it plans to invest Rs 70,000 crore more. That is the reality of the situation but it’s a little more complicated than what people end up believing in.

7) So, what’s the way out of this? Instead of just looking at WhatsApp forwards and other social media posts and panicking, it makes more sense to do something about the entire situation. First and foremost, don’t keep all your money in one bank. Spread it around in at least three banks. This will make sure that even if one bank ends up in trouble, you will continue to have access to money.

Second, the bulk of your money cannot be in a cooperative bank. There are more than 1,500 urban cooperative banks. Also, these banks are not the best examples of transparency going around. There is no way for a normal person to figure out which is a good cooperative bank and which isn’t. In this situation it makes sense to have the bulk of your money in commercial banks. This is not to say that there are no good cooperative banks out there. It’s just that it’s difficult for a common man to figure that out.

Third, this is something I simply don’t understand. There are public sector banks out there which have a bad loans rate of 20% or more. This basically means that for every Rs 100 they have given out in loans, Rs 20 or more hasn’t been repaid for 90 days or more, on an average. What additional things do these banks offer vis a vis other public sector banks? Why are you still banking with these banks, if you are? There are better banks and better public sector banks out there. Please stop banking with these banks.

And when it comes to WhatsApp, use it as a fun device to send forwards like this (which I have tweaked a little): “An unfortunate person is one who had planned a trip via Cox and Kings on a Jet Airways flight, invested money in a PMC Bank FD and a Dewan Housing Finance NCD, bought a flat in JP in Greater Noida, had an RCom sim card, bought diamonds from Gitanjali and is currently staying in Delhi.”

A version of this essay was originally delivered as a talk at the Bangalore Literature Festival on November 10

www.newslaundry.com