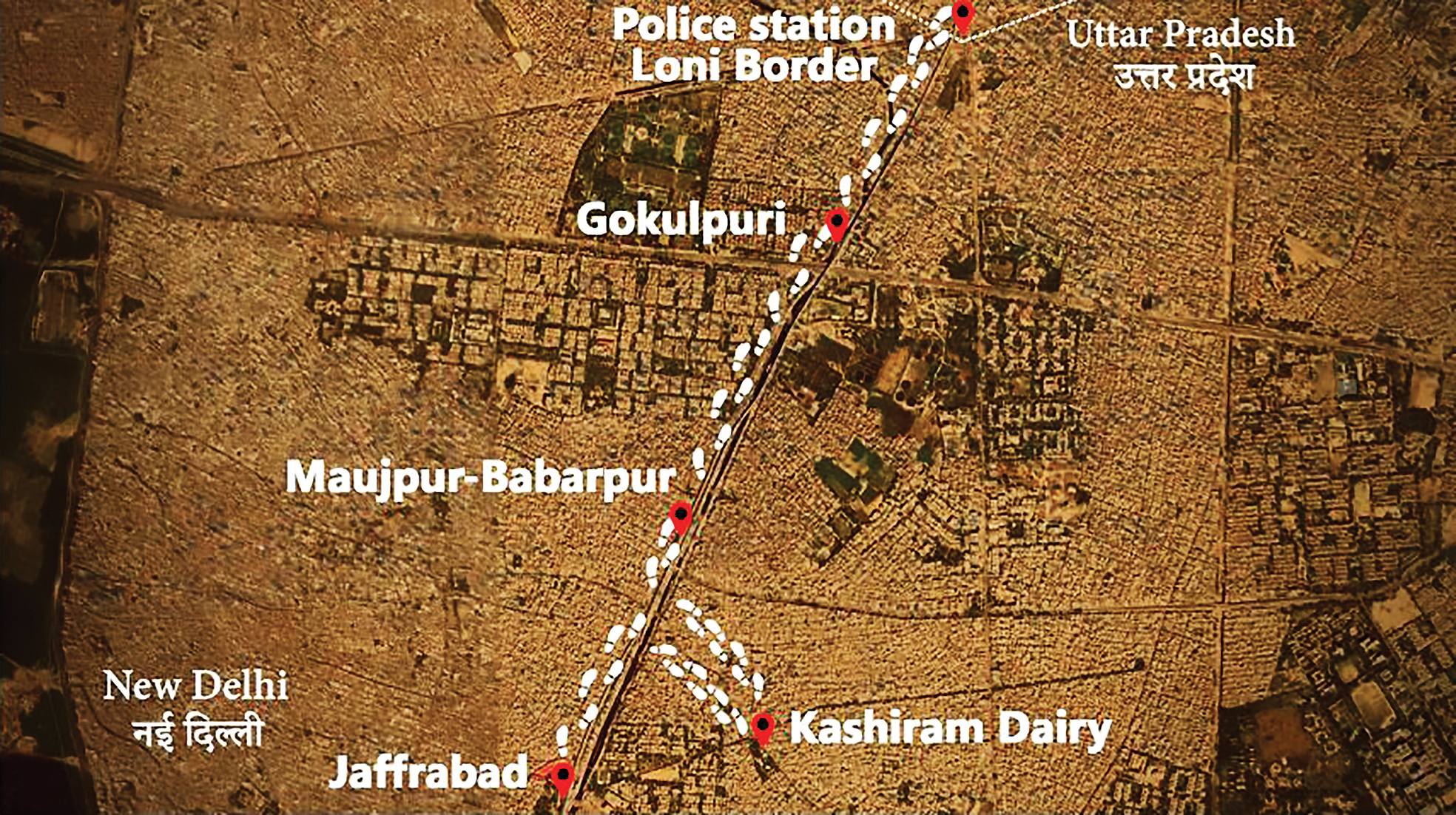

From Jaffrabad to Gokulpuri, armed men prowled the streets, homes burned, and police stood watching: An eyewitness account of Mob Raj in North East Delhi on the night of 24th

THE BILLOWING smoke could be seen from quite a distance. As I travelled on the metro through East Delhi’s Karkardooma, plumes of grey smoke several kilometres away disfigured the horizon. Below, the passing localities became more and more deserted as I approached the Welcome metro station.

“This metro will not go beyond this station. We apologise for the inconvenience,” a voice announced.

The next station was Jaffrabad — the site of the sit-in protest by Muslim women against the Citizenship Amendment Act and the proposed National Register of Citizens. Three autorickshaws refused to take me to Jaffrabad until one finally agreed.

The protest site at Jaffrabad was vibrant at 5 pm. Women sat on the road under the metro station, men surrounding them on all sides. There were paranoid whispers about “RSS men” who might have “infiltrated” the protest to cause trouble. Companies of Central Armed Police Forces personnel stood behind the men. A garbage dump nearby was on fire

The road leading from Jaffrabad to the Maujpur metro station — a kilometre-long stretch — was deserted. It was a buffer zone of sorts. The shops, schools and mosques were locked. An occasional dog would run about, and people looked on from terraces with suspicion. Personnel from the armed forces were deployed at various points, ordering a meandering few to get inside their homes.

It was as if I had been transported to downtown Srinagar in August 2019, days after Article 370 was suspended and heavy restrictions were imposed on movement in the valley

At the Maujpur-Babarpur metro station, Hanuman Chalisa blared from speakers as men armed with sticks and rods stood by and chanted religious slogans. A senior CAPF officer, learning that we were from the media, told us to not meddle with this crowd. “Take the opposite road,” he told us, pointing towards Babarpur.

In Babarpur, men of all ages congregated confidently outside bylanes, brandishing sticks and rods. Boys as young as 10, wielding rods, accompanied them. There were very few women. Often, a procession of armed men with covered faces chanting “Jai Shri Ram” would pass by, and men would shrink back to the footpaths and chant along.

I last visited this area on January 26, when Home Minister Amit Shah — then introduced as “Hindu Samrat” campaigned in a neighbouring street in Babarpur. From a stage erected adjacent to a temple, Shah had asked the crowd to vote so fervently that its “shock” would reach Shaheen Bagh. The security presence was significantly tighter then, with RAF and Delhi police personnel forming a human chain of several hundred metres and managing traffic and citizens

But there was none of that now. In the couple of hours I spent here, only one company of 15-20 CAPF men marched along this road.

The sense of security among people at Hindu-dominated Babarpur was evidently greater than among those at Muslim-dominated Jaffrabad. As the Babarpur road stretched towards Shahdara, boisterous, spirited men distributed tea to passersby. At one place, a marriage reception was being held. The road was busy and families exchanged pleasantries and gossip about the “danga” in the neighbouring area.

Then I reached Shahdara.

Here, a black double-storeyed building lay ransacked. Its signboard said “Playboy”, and broken, smouldering objects lay scattered on the road. The air outside the shop was fragrant, reminiscent of an expensive, high-end showroom. A couple of boys scavenged the charred remains, hoping for precious takeaways.

“The shop belonged to a Muslim, so it was destroyed,” a middle-aged man with vermillion on his forehead told me. “If the owner came, we would have killed him too. They’re doing this to Hindus in Jaffrabad, and we’re doing this here.”

At around 8 pm, I returned to the Maujpur-Babarpur metro station. The armed group had dispersed and the Hanuman Chalisa had stopped, but men with menacing frowns still roamed the area. The main Maujpur road was ugly, with red and grey stones, the fences around the divider razed to the ground.

In Vijay Park, a predominantly Muslim neighbourhood, men were grouped near the bylanes. They claimed that rioters from Maujpur were sneaking in through these bylanes and attacking them. Locals claimed that a daily wage worker named Mubarak Hussain had been shot and killed around noon. The situation had been so tense that his corpse was only taken away in the evening at about 7 pm.

“He was in his late 20s and hailed from Bihar,” said Raees Ahmed, a local. “We had to keep his dead body on the main road so that the police were forced to take notice and take it away.”

Mubarak was shot in the chest. Ahmed showed me a video on his phone. It was made by someone on the other side of the Shahdara drain, and captured a man wearing a red T-shirt and a helmet shooting three times inside the lane where I now stood.

“This one, this is the shot that hit him,” Ahmed said, yelping when the third shot was fired.

Locals in Vijay Park alleged that it was “goons” from the Bajrang Dal and the Shiv Sena who led the communal violence in the area, with the help of the Delhi police. “It all began with Kapil Mishra’s speech on February 23,” a young man told me, and others nodded.

As we stood there, a rumour rippled through the area. Young men who had been standing near the main road said a curfew had been imposed, and that the police would shoot anyone lurking outside. Within minutes, people panicked and the groups dissipated. Vijay Park turned eerie and still.

A man named Nafees then walked up to me and said the forces had likely detained his injured friend at the nearest checkpost, about 50 metres away. The friend had a fractured leg and was returning home from the hospital. Nafees sheepishly peered towards the checkpost, scared he would be shot if spotted. He couldn’t locate his friend

Just then, a man and woman appeared out of nowhere and began walking towards the checkpost. “Where are you going? Go home!” Nafees shouted at them. “The police are on the streets.”

The man pleaded: “Sir, we have been stuck in Maujpur for the last two days. We live in Welcome. We want to go home now.”

Nafees told them to raise their hands, like disarmed combatants in war movies, and proceed. The man, instantly convinced, lifted his hand and began walking. The woman complied too.

It was a tragicomic sight.

I took down Nafees’s telephone number, telling him I would check with the police about his injured friend. “Take care, bhaijaan,” he shouted from a distance. At the police checkpost, I was told that no injured person had passed through.

I met other journalists at the checkpost. We decided to walk to Gokulpuri, a couple of kilometres away. As we ambled down the main road, the sights and scenes were almost dystopian: stones strewn, abandoned streets with yellow lights, and dark shadows. Tattered banners fluttered above the Shahdara drain, torn to pieces by stone-pelting from both sides. A charred tractor stood in the middle of the road.

A few hundred metres before Gokulpuri, where the main road curved towards Yamuna Vihar, we encountered barricades and a dozen men lurking around them. These were Hindus who were afraid that Muslims from across the Shahdara drain would attack their colony. They carried rods and sticks.

There was suspicion — “are you recording us?” — that was partly doused after they checked our press cards.

“The police came here at 6 pm yesterday and left at 8 pm,” said one man, reeking of alcohol and visibly upset. “We need safety. If they [Muslims] come here and torch the cars and scooters, what will we do? We are protecting ourselves.”

He added: “We want peace and harmony. Even ordinary Muslims want the same. But the people causing the violence are extremists.”

We skirted Gokulpuri, where Hindu residents had barricaded the colony’s entrance and men on guard looked on suspiciously at outsiders. Following the metro line, we reached the Loni border, where Delhi ends and Uttar Pradesh begins.

As we talked to officers at the Loni Border police station, dense smoke rose from the area behind the station. We reached the spot and saw a raging fire inside a slum located right beside a drain. It was 10 pm.

Groups of men were gathered on one side of the wall, beyond which the slum was on fire. They shouted “Jai Shri Ram” and dispersed. On the other side of the drain stood two police officers, watching. They seemed to have little clue of what had happened. They asked me not to ask questions and told me to leave.

I crossed the drain, and slum dwellers provided an account of what went down: dwellings belonging to Muslims had been torched around 9.30 pm, allegedly by members of the Bajrang Dal. The Muslim residents — about 20 of them — had left a day before, because residents in the surrounding Ganga Vihar and Johri Enclave, predominantly Hindus, had asked them to.

The residents who talked to us were Dalits of the Mahavat caste. Their houses were spared but they were angry and upset. “The men wore masks and told us that we will not burn your houses because you are Hindus,” said one man who had tried to douse the flames. “We were torn. The Muslims are our neighbours and the arsonists were Hindus: how can we oppose either?”

“What if the fire leapt to our dwellings?” asked another resident, almost shrieking with rage. “Our children sleep inside at this hour. We are poor, we earn Rs 1,500 a week by putting up nazarbattu (an amulet of lemon and chillies) in people’s homes and shops.”

About 100 metres away, men gathered at a bridge over the drain. Religious sloganeering was in full sway. Slum residents told us the men belonged to neighbouring localities, and that we should not deal with them.

By now, cops had shown up on the other side of the drain, one of them armed with a carbine. However, they did nothing, telling me they couldn’t act because they were from the Uttar Pradesh police, and the bridge falls in Delhi.

Their barricade was the border.

Beyond the barricade, masked men with rods prowled outside Johri Enclave. We yelled and asked them to engage with us, but they refused. So, we crossed the barricade and met a couple of unarmed men. They told us they had no idea how the slum had caught fire.“We are only concerned with our street,” said one resident.

As we spoke, two bikes bearing four men zoomed down the street. “Jai Shri Ram,” they yelled, twice.

Two of the journalists I was with left their phones behind and walked to the bridge. Here, they met two Delhi policemen. The cops told them to leave, saying they couldn’t guarantee their protection.

How right they were. Minutes after the two journalists returned to the barricade, a mob began heading towards us. The clink of their rods drew closer. “Mulle media banke aaye hai. Maaron salon ko. Media waale hai,” they shouted. Muslims have come here disguised as journalists. Beat them up!

The police’s shoot-at-sight orders were a piece of fiction in this part of the city.

At the barricade on the border, we found a sense of safety in Adityanath’s Uttar Pradesh. But the Uttar Pradesh police officers now told us to leave. Women from the terraces shouted, “Bhaago”. So, we turned around and walked back as fast as we could. I tried not to run, lest other locals ahead panicked and ganged up against us.

It was now 11 pm. Huge waves of leaping fire had consumed the slum dwellings. Small, diminutive fires had taken over. No one knew where the Muslim residents had gone, not even their neighbours. Wherever they were, they had nothing to return to.

www.newslayndry.com